Over the past year, hundreds of eighteenth to early twentieth–century garments have passed through the Textile Department at LACMA’s Conservation Center: royal wedding gowns, French Revolutionary waistcoats and breeches, and Victorian walking suits, to name a few. These historic costumes are part of the recently acquired costume collection to be featured in the upcoming exhibition Fashioning Fashion, opening this fall in the new Resnick Pavilion. One of the exhibit’s highlights is a diaphanous pink silk gown from the 1830s. The skirt is decorated with a sea of faux pearls which weigh down the sheer silk and would click together lightly as its wearer moved.

Collaborations between LACMA’s Textile Conservation & Research Departments reveal these faux pearls were manufactured in a curious manner: delicate and hollow glass beads were filled with a slurry of material derived from fish scales and gelatin or sturgeon glue. This slurry coated the interior face of the hollow bead creating an iridescent, or in this case pearlescent, effect. This curious technique was developed by a seventeenth-century French rosary maker. The story goes that the rosary maker, Jaquin, while vacationing in Burgundy, observed that a tub in which fish were soaking bore a film of silver particles on the water’s surface. Skimming these particles and dehydrating them, he was left with a lustrous powder. He felt he had the makings of an iridescent pigment and began experimenting in the manufacture of faux pearls. Initial trials (and a suggestion from a clever female customer) determined that the pigment only held fast to the glass surface when applied on the inner surface of a bead, injected in one hollow end of the bead and allowed to drain out the other end. When applied to the outer surface, the necklace wearer’s body heat and sweat dissolved the coating, creating a mess. This trade secret was closely guarded until 1716 when it was outed by famous French naturalist M. de Reamur, whose knack for experimental study led him to work out numerous trade and ancient manufacturing secrets. After Reamur’s revelations, this manufacturing technique became common in Europe and faux pearl beads produced in this manner decorated historic costume in the centuries to follow.

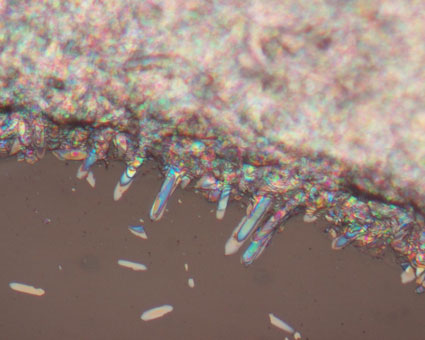

These images show the even manner in which the coating covers the inner part of the bead. A small drop of the slurry was swirled around inside the bead. LACMA Associate Conservation Scientist Charlotte Eng was able to separate the pearlescent coating from some broken beads. Magnified images show the platelet-like guanine crystals which give fish scales, and the pigment found on these beads, their iridescent appearance. Pretty neat stuff.