John Biggers was a muralist before his geometrical phase was to come into promise. He came of age in the era of social realism, a time of the great mural painting led by Diego Revera and the Mexican Revolution. Biggers became the great muralist of the Negro’s movement toward self-realization and self-esteem. This was the time of segregation, the time of Jim Crow. It was a very different world, indeed. Heavy, sad, and palpable fear of the “other” held sway over one’s every action. A time exemplified by Ralph Ellison’s novel, The Invisible Man! A world of “skin,” light and dark! For Biggers, this was not mere art but the narrative journey of a people in a sulphurous atmosphere of oppression, denigration, and paranoia—the other side of the American dream. Racism had left a people in a desperate search of a self-image that honored them, that represented their humanity. And Biggers’s art, along with Charles White, a mentor, and many others, was still feeling the heat of the Harlem Renaissance, a community collective whose self-image had been driven by this blighted thing, this race drama. Though the measure of this could vary to some extent, its presence seems to cast a shadow over all their work.

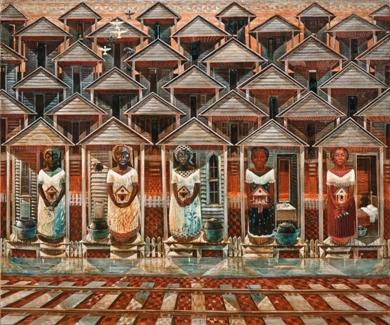

John Biggers, Shotguns, 1987, courtesy of William O. Perkins III

Biggers would found an art school. He would make a mind-altering trip to Africa and all the elements of Shotguns, this gem of geometrical realism, would have evolved from his earlier work. Biggers vacillated in styles, as if in constant search for that pictorial union of his muralist social realism and the ever-imposing tenets of geometrical modernism, with its undeniable African roots and unspecified spirituality. Shotguns would become a masterpiece of that union.

Today, oddly, in some postmodern parlance the painting may come off as some altered state, a play on pixilated chromatic color or even some mysterious exercise in triangular patterning. Biggers painted Shotguns in his retiring years, and the thread of reconciliation with his immutable past runs constantly through his various mediums of idealized fantasies. Here Africa is the motherland and the women wear white and float through geometrical non-objective atmospheres in some ethereal space. Having evolved from the earlier dense, weighty sadness in the tight grouping of The Cotton Pickers, like blocks of sandstone, to the later airy, bird-like imagery that seems bound for flight, Biggers balanced his emotional world. And, like William Blake, the awaiting world was upward.

Shotguns has the scale of a moderate-sized painting, but thematically it is a grand mural, evoking an entire world, a Negro world, luminous, colorful, yet somehow natural with weathered wood surfaces dispelling our certainty in the vague “otherness” that Biggers lays before us. A quilted sky and a quilted earth, a patchwork landscape, the stacked empty humble shotgun houses elevated, towering majestically, even the receding shadows, resides in triangular profusion. At their base five women, pillars, possibly symbolic pillars of memory, the three African masked faces, distant, unattainable “past” doors, and the two grandmothers, realistic and maybe even portraits with visible interiors, are somehow recent and accessible. The evil-catching cast-iron pots are circular forms set off in a sea of angles. Biggers imbues every point of the surface with symbolic weight, shedding its light kaleidoscopically; the triangles abound like gems beckoning us. Even the birds, except one, fly upward in this divine shape. Shotguns is a repetitive pulpit visual narrative. John Biggers, being not merely romantic, envisions a quasi-religious ascendancy through the faceted grammar of an existential dream.

Hylan Booker