Working on the exhibition David Smith: Cubes and Anarchy over the past six years has caused me to muse more than once on “lineage”—the many relationships each of us has to history. Let me explain.

Renowned American sculptor David Smith (who was born in 1906) briefly attended the University of Notre Dame and worked one summer at the Studebaker automobile factory, both in South Bend, Indiana. I was born and grew up in South Bend and my father was on the faculty at Notre Dame. Pure coincidence, but it makes me feel connected, a part of a historical trajectory.

David Smith: Cubes and Anarchy is the first major exhibition on the West Coast devoted to this outstanding sculptor in over forty-five years. The last one, also at LACMA, opened in November of 1965. It was organized by Maurice Tuchman, who was the head of my curatorial department (then known as Twentieth-Century Art) when I first arrived at the museum as a curatorial assistant in 1984. Another personal link in a historical chain.

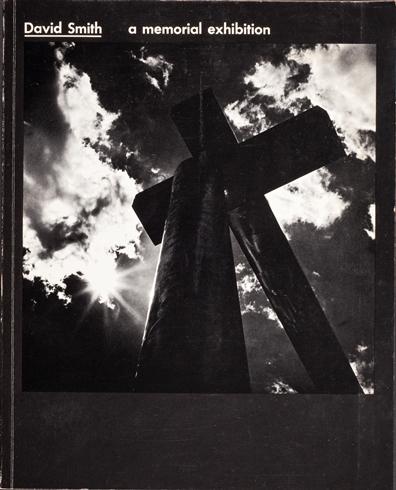

The two exhibitions are very different, however. Cubes and Anarchy is a thematic exhibition—including not only Smith’s sculptures but also his drawings, paintings, and photographs—tracing the sculptor’s use of geometry from the very first years of his career in the early 1930s to his unexpected death in 1965. LACMA’s 1965 show, by contrast, started out as an exhibition of then-recent large-scale sculptures—a dozen from the Cubi series and two from the Zig series—all made between 1961 and 1965. On May 23, 1965, in the midst of the preparations for that show, Smith was killed in a car accident at age 59. As a result, the show became David Smith: A Memorial Exhibition. As Anne M. Wagner writes in the Cubes and Anarchy catalogue, “The [1965] catalogue...took up the task of mourning, its cover speaking...of tragic martyrdom, and its concluding photograph—the artist’s welding helmet, still sitting where he had left it in the studio—offering a more subtle and immediate evocation of bodily loss.”

Since 1965 David Smith has ascended into the artistic pantheon, not only of great American artists but of all great artists. So, for the art historian and curator—for me, that is—as well as for the visitor to Cubes and Anarchy, the sense of a personal connection to this remarkable artist is now enhanced by a broader cultural perspective.

Carol S. Eliel, Curator of Modern Art