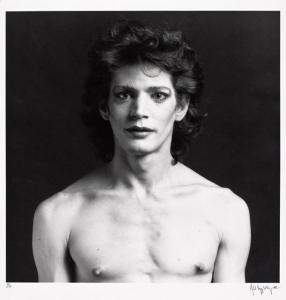

If you wander through the current exhibition Human Nature: Contemporary Art from the Collection, you will find photography, video, and installation work in amongst the usual suspects—painting, drawing and sculpture.

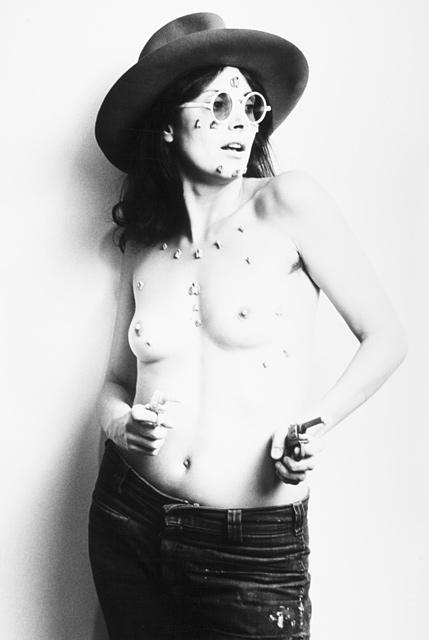

Hannah Wilke, S.O.S. Starification Object Series (guns), 1974 Purchased with funds provided by the Judith Rothschild Foundation, the Modern and Contemporary Art Council, and the Ralph M. Parsons Discretionary Fund

That wasn’t the case so long ago, when photography, as a practice or when displayed, was considered in terms that separated it from the rest of the contemporary dialogue. Then Cindy Sherman and a few others happened.

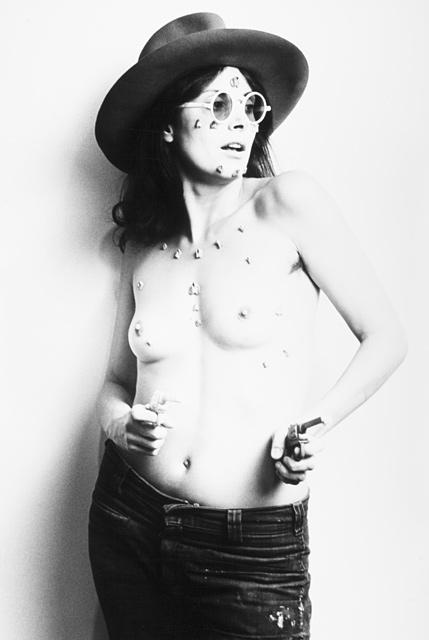

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait, 1980, The Audrey and Sydney Irmas Collection, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

Now we have photo imagery everywhere and, I hope, a greater appreciation for the medium—though one could make a case for oversaturation—and its challenges. In fact, a lot of artists using photography (see Baldessari) are creating work that retells photo history or plays off those very elements that initially entranced, namely the depiction of the real.

Yinka Shonibare, Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 21.00 Hours, from the Diary of a Victorian Dandy Series, 1998 Purchased with funds provided by the Modern and Contemporary Art Acquisition Fund and the Ralph M. Parsons Fund

No longer are we able to look at photographic imagery and have an expectation of truth, and there is an understanding that a photographer “makes” his/her images rather than “takes.”

Nikki Lee, The Hispanic Project (25), 1998 Ralph M. Parsons Fund

With photography incorporated into the larger picture of modern art history, a different story of influences, themes, and concepts emerges.

Eve Schillo