This weekend LACMA added eight new works to its collection through its annual Collectors Committee events. All week on Unframed our curators will be highlighting the objects just acquired.

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino (De español y morisca, albino), c. 1760, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee

Casta (“caste”) painting is one of the most compelling forms of artistic expression from colonial Mexico. These three works belong to a set of castas by Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz that originally had sixteen scenes (over time many sets have been disassembled), and it is one of the finest of the genre. Morlete Ruiz was an influential member of a painting academy established in Mexico in the mid-eighteenth century, who was deeply attuned to ideas of pictorial innovation.

What makes the paintings so exceptional is what they illustrate three centuries before multiculturalism became fashionable: the intermingling of races in colonial society. Each scene depicts a family group with parents of different races and one of their children. During the colonial period Indians, Spaniards born in Spain as well as the New World (the latter known as Creoles), and Africans brought over as slaves all populated Mexico. The result was that a large percentage of the population became mixed, known collectively as castas (or “castes” in English)—from where the genre derives its name.

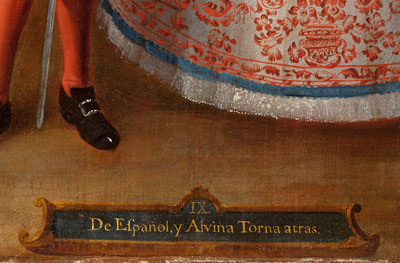

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, From Spaniard and Albino, Return Backwards (De español y albino, torna atrás), c. 1760, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee

Casta paintings were largely produced for a European audience to classify and create order of an increasingly mixed society. This is especially important because in Europe there existed the widespread idea that all the inhabitants of the Americas (regardless of race) were degraded hybrids, which called into question the purity of blood of Spaniards and their ability to rule the colony’s subjects. Casta painting responds to this anxiety by constructing a view of an orderly society bound by love (hence the use of the familial metaphor), but one that was hierarchically arranged and that featured Spaniards at the top.

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, From Spaniard and Return Backwards, Hold Yourself Suspended in Mid Air (De español y torna astrás, tente en el aire), c. 1760, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee

In his works, Morlete Ruiz situates the mixed couples in elaborate landscape settings and pays careful attention to the figures’ clothing and attributes. For example, some Spanish men hold a sword—a privilege that in colonial legislation was only reserved to this group—while some women sport a manga, a cape that resembles an inverted skirt fit from the head, worn exclusively by women of African descent ( it was adapted from a similar garment worn by Moorish women in Spain).

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, From Spaniard and Albino, Return Backwards (De español y albino, torna atrás), c. 1760, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee (detail)

In addition to presenting a typology of human races, occupations, and dress, casta paintings picture the New World as a land of boundless natural wonder through precise renderings of native products, flora, and fauna. Morlete Ruiz’s works include an assortment of local fruits such as avocados. Products like these underscored the colonists’ pride in the diversity and prosperity of the colony, and at the same time they fulfilled Europe’s curiosity about the “exoticism” of the New World. In addition, they reflect the popularity of classificatory theories introduced by the Enlightenment and the interest in natural history.

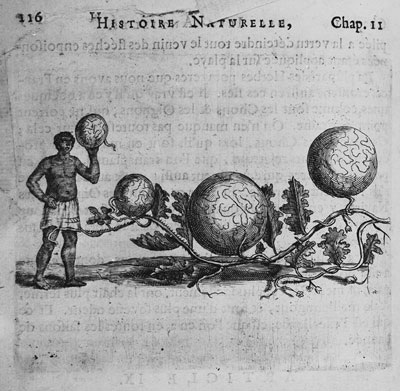

Native American and Watermelons, from Charles de Rochefort, Histoire naturalle et morale des iles Antilles de l’Amerique (Roterdam, 1658).

This print, for instance, was included in a seventeenth-century book about the natural history of the New World. The artist resorts to the same formula of juxtaposing human types with local flora, except that here he includes a group of giant melons. This is in keeping with the general idea that Europe had of the Americas as an unusually hot place due to its geographic location, one where nature and people (regardless of their racial makeup) ripened and spoiled quickly. The overgrown fruit points to the unruly superabundance of the land and to its quick degradation.

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, From Spaniard and Return Backwards, Hold Yourself Suspended in Mid Air (De español y torna astrás, tente en el aire), c. 1760, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee (detail)

Casta paintings respond to this idea by emphasizing the natural bounty of the Americas, and by emphasizing the superiority of Spaniards. If people degenerated, it was not due to the heat of the region (hence Spaniards where not affected), but to where they fell in the racial scaffolding—that is, to their type of mixture.

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, From Spaniard and Albino, Return Backwards (De español y albino, torna atrás), c. 1760, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee (detail)

Indeed, the basic premise of the castas genre as articulated through its inscriptions, is that the successive combination of Spaniards and Indians resulted in a vigorous race of unadulterated white Spaniards after three generations. The combination of Spaniards or Indians with blacks, however, led to racial degeneration and the impossibility of returning to a whiter racial pole. This inscription, for example, refers to the mixture of a Spanish male and an Albino woman (Albinos were misguidedly believed to descend from blacks), which beget a torna atrás, literally a return-backwards, an expression by which was meant that their offspring receded in the racial hierarchy by moving away from the “whiteness” of pure Spaniards.

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, From Spaniard and Albino, Return Backwards (De español y albino, torna atrás), c. 1760, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee (detail)

What makes casta paintings so compelling is the tension between the story they tell and how they tell it. On the one hand the works rank each racial group and articulate its place within an “invented” racial order. At the same time these are highly estheticized paintings that function as proud renditions of the local: their exquisite assortment of fruits and textiles alone make them fascinating images of the material culture of the period. And one cannot fail either to notice the great tenderness among the figures which serves to mask any sense of racial tension.

In 2004 I organized an exhibition of these fascinating works at LACMA titled Inventing Race: Casta Painting and Eighteenth-Century Mexico. Since then, we are constantly asked by the public about the works and whether we have any in the collection. Now we do! These paintings by one of Mexico’s most notable eighteenth-century masters will provide an important anchor to discuss the origin of racial perceptions and their ongoing effects in today’s society—a subject that is especially poignant in a city like LA. We will feature the paintings soon, in an upcoming reinstallation of our Spanish colonial galleries among many of our recent acquisitions. Stay tuned.

Ilona Katzew, Curator and Co-Department Head, Latin American Art