A product of the “Steel Age,” David Smith’s medium was of the grand skyscrapers, suspension bridges stretching over waterways, the vast railroad system that had etched its steel lines into the American landscape. This was one of the mediums through which the language of modernity would coalesce. No DC Comics superhero! Steel, David Smith said, “possesses little art history. Its associations are primarily of this century, it is structure, movement, progress, suspension, cantilever, and at times destruction and brutality.” An artist with an uncanny vision, Smith realized the world in different terms. His was a journey that ends in geometrical abstraction; agnostic symbols attest to the concept of modernity and yet devise unquestionable states of purity, a universe of strict forms. In exhibition curator Carol S. Eliel’s essay “Geometry in David Smith,” which is the raison d’etre of the retrospective that closes this weekend, she expresses her intent: to reveal a sculptor who “adopt[ed] the geometric forms and utopian aspirations of the international constructivist avant-garde from the very first years of his career in the 1930s until his untimely death in 1965.”

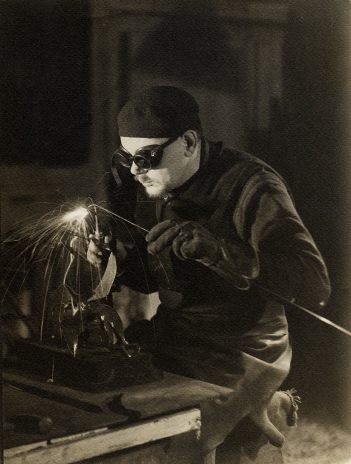

Dan Budnik, David Smith Welding “Primo Piano II” in His Bolton Landing Workshop, 1962, © Dan Budnik

In Smith’s passionate hands the noble savage is the working man. It was the 1930s, and workers’ rights was the air you breathed. His crucible would be the Studebaker factory floor; a “eureka” moment of seeing Pablo Picasso and Julio González’s collaborative iron constructions in a 1931 issue of Cahiers d’ Art; and reinforced in the Russian Constructivism of Rodchenko and Malevich and Tatlin, which blurred the distinctions between art and manufacturing. Within these parameters, Smith is the rebel artist with geometric vision, the soul of a poet and the heart of a working stiff. He defiantly favored Karl Marx as a subject matter. And to this end (possibly romantically), he was a card-carrying member of United Steelworkers Union of America, local 2054, straddling what could be an existential divide of his aesthete’s ambitious dreams and energies.

David Smith, Star Cage, 1950, Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, the John Rood Sculpture Collection, photo courtesy the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota

Lifting steel into space as none other, his geometry would float off the page of his drawings and photo montages, the steel relieved of its weight. Spending time with it in the gallery, I witnessed the lyrical dance in the space of Star Cage, where sculpture fuses into tensile rods and geometry is isolated in its negative areas. Also found in the exhibition catalogue, Anne M. Wagner’s “Heavy Metal” essay puts forth that “…welding and metal were synonymous with modernity…” and she characterizes Smith as “the twentieth-century prosthetic god,” as he was fully dressed in welder’s regalia.

David Smith, The Hero, 1951–52, Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsey Fund 57.158, © The Estate of David Smith/VAGA, New York, photo courtesy Brooklyn Museum of Art

Smith’s Hero sculpture, maybe inspired by Constantin Brancusi’s Bird in Space except for the base and the head, offers none of the solidity in its spare, extraordinary lightness, as if a man was simply brushed in air. In spite of the angles, the volume, the defying “gravity,” as Clement Greenberg would say, there is certainly a sort of imposed melodrama about the work, placating the ghost of Roman power and parables of the plowshares and the swords which creeps around his title. Anthropomorphic touchstones tied to some visceral need to stay grounded, knowing secretly that the steel had its own life.

Installation view of David Smith: Cubes and Anarchy, © The Estate of David Smith/VAGA, New York, photo © 2011 Museum Associates/LACMA

I can sense his homage to Mondrian as the bright, playful and daftly humorous circle and rectangle steel pieces of yellow, blue, and red in Bec-Dida Day and the orange of Circle III, sends mixed messages of artful logic and cosmic radiance. Smith was a confessed painter using a different canvas. His last balancing act was the baroque boldness of his Cubis, their weight and power dispelled through with deep burnished “gestural” swirls, an abstract expressionist act, giving the surface an eerie transparence, the sculptures’ mass almost mimicking a human presence. The man of steel claimed earlier, “I would prefer my assemblage to be the savage idols of basic patterns,” for even in the delicate surface there is still something savage, which he prefers to place against nature, though nonetheless triumphant, and a wonder. And we too are in wonder at the enterprise that guides us, willingly, through the last great conversation of modern art in this very human adventure.

David Smith, Cubi I, 1963, Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, Special Purchase Fund, © The Estate of David Smith/VAGA, New York, photo © Detroit Art Institute of Arts/licensed by The Bridgeman Art Library

Finally, Robert Hughes in a 1983 Time review quotes his close friend Robert Motherwell’s valediction, “Oh David, you were as delicate as Vivaldi and as strong as a Mack Truck.”

Hylan Booker