One would think that Ellsworth Kelly’s abstract art was easy, being so casually blissful. And bliss is a quality one could readily associate with the beautifully curated exhibition, Ellsworth Kelly: Prints and Paintings, which is on view in BCAM through April 22. There is this sort of simple clarity, which by its very nature is a kind of misdirection. And for those in the know, it might be there on the face of the work, but for me, I had one of those “doors of perception moments” that made looking at the work feel as if I were seeing it for the first time. And suddenly, and amazingly, it was quite thrilling.

Installation view, Ellsworth Kelly: Prints and Paintings, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, January 22–April 22, 2012, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

I thought Kelly’s geometry was about geometry. But to me it’s about space—the stuff in between the drawn lines, the transient shadows, the reflections thrown on the floor—the what’s inside the outlines and the perfect color to hold space in check. Not merely apertures that shape the world in this odd way where Kelly is prepared to color, but instead his looking through these shapes with reverence and uncanny wisdom. Kelly, though eighty-eight years old, may well be from the future with an aesthetic purity that empties—or almost empties—the world of things. Nature is there, but only as a gesture.

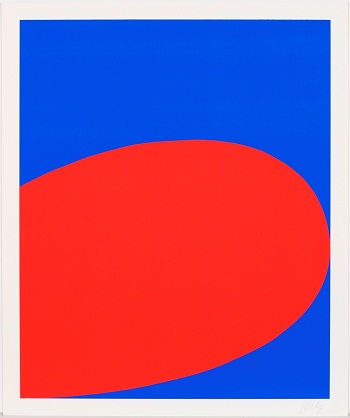

Ellsworth Kelly, Red/Blue (Untitled) from the portfolio Ten Works by Ten Painters, 1964, screenprint on Mohawk Superfine Cover paper, collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer, © 2012 Ellsworth Kelly and Wadsworth Atheneum, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

If cyberspace had a realization, surely it would appear somewhat like Kelly’s universe where the portmanteau of geometry and biomorphic nature collude to give us “biomorphic geometry” in vivid, saturated spectrum. This compelling fusion crystallizes in the prints, for it may be that the medium meets its perfect form or the perfect form meets its ideal medium. Bright and joyous, the prints seem to suggest Kelly disentangling the intrinsic connotations from mere visual clichés, bringing the image closer to nature’s amoral fauna display, like a bed of flowers. I feel that the colors lay together, intimate like lovers with their charm and vitality—pure eye candy. And as if the lights had gone out, he darkens the cascade of color, and then black elegantly assumes all the roles. And if viewed, prosaically, he harnesses the energy in these extraordinarily large curves, something like the arc of a windshield wiper or the slices of succulent melons sometimes graphed on a triangle-cut space, trapped as incomplete moons, orphans of that perfect shape: the circle.

Installation view, Ellsworth Kelly: Prints and Paintings, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, January 22–April 22, 2012, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

You would think by now that with the shapes, the intense colors, and the sheer abundance of its consumer cousins, there would be nothing left to say. And yet, viewed without the constant labels—those imposing words—they are set free and live in the realm of ideas and wonderment. So very different from Kandinsky’s and even Malevich’s abstractions, while nonetheless using somewhat the same elements, Kelly seems to purify them, release them of any associative melancholy neurosis or the dense dreamscape scaffolding or any apparent atavistic urge. That is not to say that the past didn’t inform him or to deny that a twelfth-century stained glass window wasn’t a form of inspiration. Nor is there any over abiding theory of perception, a Gestalt, a big reality superimposed on the painted object. Maybe it’s just the looking—the existential moment itself and the pure glamour of color.

Installation view, Ellsworth Kelly: Prints and Paintings, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, January 22–April 22, 2012, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

And in that sense Kelly is utterly visceral, inside of nature and perhaps looking out, maybe devising avenues of escape but never being more than what they are: apertures, windows, shadows, and infinite interplay with infinite possibility—the cosmic touch. But, of course, there is the meditation on the perpendicular, our most human need, architectural in its understanding. Here Ellsworth Kelly is relentless.

Installation view, Ellsworth Kelly: Prints and Paintings, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, January 22–April 22, 2012, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

There’s something quite haunting in these majestic rectangular pools of color with their luminous squares, curvaceous sweep of hot, boldly interfacing and intermingling personalities constantly jockeying for position of dominance. And within the heat and vibrancy, the grand question of the white wall, the other framing, the would be vacuum, the grand negative—this apparent empty space that goes on suggesting that it is always in play, an abiding reality of his art, for it is always “a room with a view.”

Hylan Booker