Drawing Surrealism features 250 works from surrealist artists from around the world and is on view at LACMA through January 6, after which it travels to the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. Hollis Goodall, curator of Japanese art, discusses the origins and influence of surrealism in Japan. In my studies on Japanese art, either modern or pre-modern, I often find that the groundwork for a seemingly entirely foreign or new style was laid in past times. How did surrealism catch on in Japan and become such a dominant force, eventually involving nearly three thousand artists? Like Art Nouveau, which was popular earlier in urban Japan, having originated in Europe based upon imported Japanese Rinpa-style painting and decorative arts, surrealism may have had a familiar antecedent. In Drawing Surrealism, works by Eikyū and Hirai Terushichi in particular show cutting and reassemblage of parts, in which newly juxtaposed fragments create a sense of strange disconnect and stimulate in the viewer a new level of perception. Montage and seemingly random juxtaposition were popular expressive manners in both Japanese film and advertisement of the 1920s and 1930s, and those methods were already familiar to the consumer to which they appealed through woodblock print composition of the preceding century. Back in the 1840s through the 1860s, particularly, the artists Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) and Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), related only by school affiliation, often combined efforts in a print series by juxtaposing seemingly random images within a single print sheet. This form of play worked as a puzzle for the viewer, who had to use his or her knowledge of popular urban culture to figure out the connections. Though not speaking to the viewer on the psychological level of surrealism, the jarring disconnect of some of these images created a habit of looking that carried forward into the modern era.

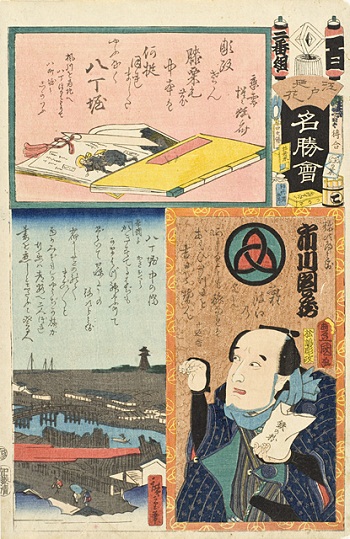

Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III), Utagawa Hiroshige II, Hatchobori and Ichikawa Danzo, 1861, gift of Chuck Bowdlear, Ph.D., and John Borozan, M.A. (M.2003.67.7)

Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III), Utagawa Hiroshige II, Hatchobori and Ichikawa Danzo, 1861, gift of Chuck Bowdlear, Ph.D., and John Borozan, M.A. (M.2003.67.7)Another member of the Utagawa school, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1862) created portraits consisting of a head assembled from bodies of nude men and also portrayed urbanites with the heads of fish, cats, or sparrows. These dream-like fantasies had a long history in Japanese pictorial art, but spoke to the subversive element in late Edo period (1615-1868) urban Japan.

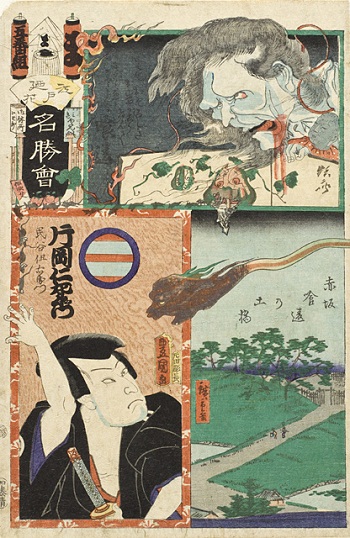

Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III), Utagawa Hiroshige, The Restaurant Mankyu; The Role Hige no Ikyu, 1852, gift of Arthur and Fran Sherwood (M.2007.152.46)

Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III), Utagawa Hiroshige, The Restaurant Mankyu; The Role Hige no Ikyu, 1852, gift of Arthur and Fran Sherwood (M.2007.152.46)It was certainly not with these thoughts in mind, though perhaps lying dormant in their subconscious, that artists developed the surrealist movement in Japan. Artists and writers revolted against the “academy” of government-sponsored art exhibitions, which had been displaying “fine art” of Japanese or European method in juried exhibitions since 1907. Avant-garde artists began to practice and disseminate Dadaist work through journals and exhibitions in 1924, a year after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake had obliterated much of Tokyo, killing more than 100,000 people and burning more than half a million residences. The era of reconstruction in Tokyo, which was increasing in population then and where now half of the Japanese populace lives, stimulated an authentic leap forward into modernism in art and literature.

Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III), Kawanabe Kyosai, Utagawa Hiroshige II, Embankment by Kuichigai Moat in Asakusa; The Actor Kataoka Nizaemon VIII as Tamigaya Iemon, tenth month, 1863, gift of Arthur and Fran Sherwood (M.2007.152.50)

Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III), Kawanabe Kyosai, Utagawa Hiroshige II, Embankment by Kuichigai Moat in Asakusa; The Actor Kataoka Nizaemon VIII as Tamigaya Iemon, tenth month, 1863, gift of Arthur and Fran Sherwood (M.2007.152.50)By 1927, the first surrealist poetic journal was edited and published by Kitasono Katue (1902-1978), and in 1928 and 1931 respectively the surrealist poet Nishiwaki Junzaburō returned from studying at Oxford and the painter Fukuzawa Ichirō came back to Tokyo from study in Paris, each becoming an informational nexus in their respective worlds. The surrealism that these artists brought with them from Europe, and that which had been conveyed in preceding years to Japan through journals and exhibitions, was mixed through a filter of the absurdist Dada style along with Futurist painting manners. New, more authentically surrealist works from Europe were displayed in a major exhibition in 1931, which traveled around the country and brought a much larger group of artists into the surrealist orbit. In addition, a photography exhibition of more than 1100 images from Germany toured the country the same year, helping to engender a movement in New Photography, with adherents such as Yamamoto Kansuke and Hirai Terushichi, who, along with other photographers in Osaka, Kobe, and Nagoya, practiced a much more subjective version of surrealist photography than had been seen in Tokyo. With these stimuli, mature surrealism developed throughout Japan in the 1930s becoming the dominant non-realistic European-derived artistic manner until the government’s “thought police” in 1941 began to arrest artists who they felt conveyed a message that ran counter to the interests of the nation.