“Out, damned spot! Out, I say! . . . Here’s the smell of the blood still: all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand. Oh! Oh! Oh!” —Macbeth

On view through Sunday, February 10, Bodies and Shadows: Caravaggio and His Legacy beautifully illustrates the power of the gesture of hands. And in a contemporary sense, Bruce Nauman’s piece For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and fingers), on view now in BCAM, suggests just how differently the twenty-first century regards these human appendages.

Compared to the evocative heavenly hands by the glorious Michelangelo Buonarroti in the heaven of the Sistine Chapel, you could almost say that Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio is the “man who fell to the earth,” where hands and feet reflect the gruff, austere reality of dirt and labor. Highly competitive and volatile, Caravaggio lived the intense life of the street, the very heart of his artistic vision. When we see these moments with real people in sort of real time and place, we sense the stark vision that was like no other. Here the compellingly theatrical came into focus. Lights! Action! (So to speak.) A hyper reality is on display.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Martha and Mary Magdalene, c. 1598, Detroit Institute of Arts, gift of The Kresge Foundation and Mrs. Edsel B. Ford, photo © 2013 Detroit Institute of Arts, all rights reserved

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Martha and Mary Magdalene, c. 1598, Detroit Institute of Arts, gift of The Kresge Foundation and Mrs. Edsel B. Ford, photo © 2013 Detroit Institute of Arts, all rights reserved

Given the magnitude of their gestures—through yards of draping cloth—these common looking lascivious boys, haggard men, and mostly serene women occupy a space that was not unlike their natural places. They somehow mirror their world, bringing tales of the Bible and mythology up close and personal. The depth of chiaroscuro for Caravaggio is not merely a technique, inspired by Raphael. It animates the very image of fear and revelation, Heaven and Hell, as the hands grope out of its dark magic. Art momentarily leaves the heavens. For me, it’s sheer beauty on earth!

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Salome Receives the Head of St. John the Baptist, c. 1609–1610, National Gallery, London, England, photo © 2013 The National Gallery, London

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Salome Receives the Head of St. John the Baptist, c. 1609–1610, National Gallery, London, England, photo © 2013 The National Gallery, London

Caravaggio and his legacy of followers would cast us as voyeurs within the narrative melodrama of the street—the dungeon, the taverns, the urban rawness that filters through a naked vision of sensuous, earthbound, tactilely transformative spiritual mysteries. We can almost touch them. Faith, sex and glamour are seen in the grip of a staff in a darkened road; seduction in an open palm in a darkened street. The hands tell of conversion, the business of butchery, the painful crucifixion, the pulling of a tooth, thievery, trickery, fierce negotiations. They hold the hair of the decapitated John the Baptist, the brooding chin, the tightened crown of thorns on Jesus's head. Divine fingers thrust forward to point Matthew out. Within this background of blood lust and barbarism, the hands of disciples and Madonnas exact tenderness, mercy, and benevolence.

Gerrit van Honthorst, The Mocking of Christ, c. 1617–1620, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of The Ahmanson Foundation, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Gerrit van Honthorst, The Mocking of Christ, c. 1617–1620, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of The Ahmanson Foundation, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

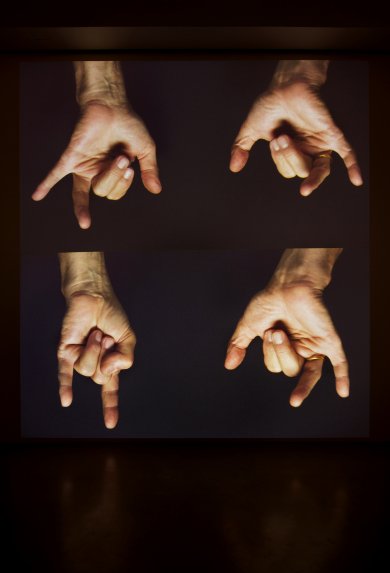

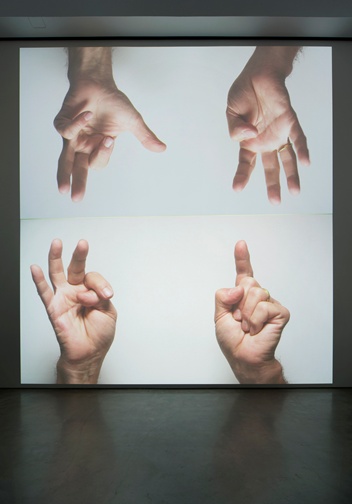

Caravaggio’s tortured, powerfully emotional tension would have many followers. His exquisite skill gave us hands as the soft malleable reality that shapes the drama of life. They tell stories through the eye of a carnal Everyman in a time of religious fervor. Bruce Nauman’s For Beginners is, on the other hand, a video writ large done in true twenty-first-century mode. One of the most body conscious contemporary artists of his generation—and working through many different mediums—he has a profound affinity with the human body. Of course, it is somewhat less about the nature of the moral spirit, and more about nature of perception itself, as it borders on ironic humor and farce.

Bruce Nauman, For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and fingers), 2010, collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Artis, image courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York, © 2013 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York,

Bruce Nauman, For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and fingers), 2010, collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Artis, image courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York, © 2013 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York,

It’s as if the issues of reality that obsessed Caravaggio had long been settled, and in the intervening four hundred years, artistic concerns turned elsewhere. Something more subtle and pointedly judicious would obsess Nauman: namely language, and the irony of signs and their bizarre intercourse. This is where he would fixate. As raw materials, the hands in For Beginners are removed from emotion. Abstracted, the hands become conceptualist gesticulating gloves, independent of specific emotion— a kind of mime in a “cool hand Luke” world. With a sort of Warholian repetition—and on giant screen—Nauman names the digits of his hands in a dual sequence. As if devolving, the sound dissolves into something less than the meaning of his hands’ motion. It is a kind of beautiful minimalism that eats at attention and communication. In this sense, Nauman seems closer to ritual, mimicking something made nihilistic or fetishistic. It’s strangely funny yet hopelessly human.

Bruce Nauman, For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and fingers), 2010, collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Artis, image courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York, © 2013 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bruce Nauman, For Beginners (all the combinations of the thumb and fingers), 2010, collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Artis, image courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York, © 2013 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As a guard, many have asked me, “What is he getting at?” Repetition can be a black hole where you are always puzzled at the beginning. Are the hands merely gestures of playfulness? Of course, this has been one of Bruce Nauman’s consistent themes—the absurd conflagration of mathematics (like the nature of Pi) with the musical structure of a broken record. Mix the paradox of language with the desired meaning, and one is stranded in some kind of loop. There’s the sensuous dance of the fingers, the background that is sometimes black, white, or both, the hypnotic voices, and the hands’ dexterity. It’s all a sort of “disconnect” engaged in an exhaustive exercise where surely we’ll smile at our own frustration. In this kind of dizzy choreography, the hands enter the theater of the absurd, and their sheer scale is sensational. Dazzled, we are caught stagnating on the edge of expectation. Maybe this is Bruce Nauman’s modern drama.

Hylan Booker

For Beginners is on view now in BCAM; Bodies and Shadows: Caravaggio and His Legacy is on view through February 10. Become a member and see it, plus Stanley Kubrick, for free.