Michelangelo’s David was my first artistic example of the male muscular body as art and its faint brethren, those alabaster physiques marching through hallways of museums. The picture of the self is made from a thousand words, half-disguised meanings, paintings, and well-intended and not-so-well-intended imagery that can obscure ideas of the self.

But the photo is another self. Art so easily becomes a thin veil through which a version of the self, some autobiographical reference—even if it’s miles off—defines oneself. Thus, it has been his—our—the black man’s ego-image search from the very beginning, which up to now has been an unattractive kaleidoscopic merry-go-around. In the procession of time, this has made black self-idealization an existential and perpetual split personality in which the culture at large and “the self” battle for supreme identity.

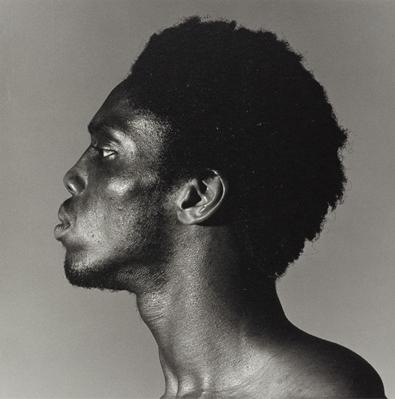

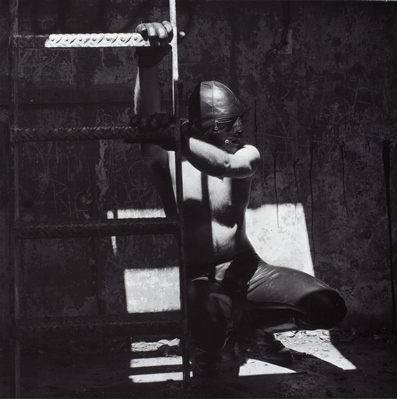

Robert Mapplethorpe, Alistair Butler, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Alistair Butler, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

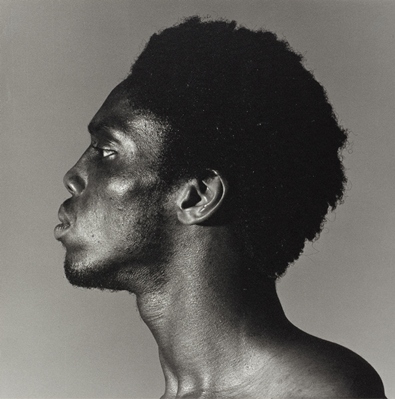

LACMA's hard-edged and gritty-though-romantic exhibition Robert Mapplethorpe: XYZ, which closes March 24, has within its dreamy, almost fortyish “Movieland” gay star quality, the challenged and somewhat exaggerated iconography of the black male as not only exotic and erotic, but also some of the most unabashedly striking images of sheer black beauty ever rendered and recorded as art. And though this emancipation by no means compares to the great 1863 one, it does enter the “temple of the muses,” disentangling the object of “derision” from the object of “desire”—that human paradox of sexuality in its most vivid form of carnality.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Leigh Lee, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Leigh Lee, N.Y.C. (Z Portfolio), 1980, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Even imagery has journeys, and particularly, this one. Out of the swampy darkness of slavery and Jim Crow—“strange fruit hanging from the popular trees”—images were fixed. The 3/5 of a persona saddled with the weight of those ludicrous tags designed to debase—Tom, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks—and a book by Donald Bogle that illustrates blacks’ film presence in the culture: a mauled version of blackness. The image moves backward and forward, sidewise and facedown, constantly transforming the cultural baggage as it shifts by fits and starts. The tight grip one had to have on the perceptions and the many contradictions between say, Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington or the cries of W.E. B. Du Bois, which extended the tension that continued between Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X—an apparent acquiescence and forthright rebellion vying for the soul of the self-image. Sports heroes and apparent villains: Jack Johnson for one era and Jesse Owen and Joe Louis for another, and yet another existential battle in the single person of Cassius Clay vs. Mohammad Ali. And this would continue on with the Black Panthers and, not to leave out the endless list of entertainers, from the black minstrels to blues Madonnas, which would play out the tragically evocative drama of self-identification. But the beauty itself as iconography remains half hidden in the debris of America’s shadow boxing in an ever-decreasing sandbox of social, racial, and sexual reality.

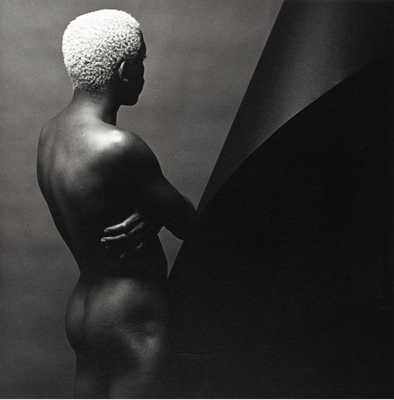

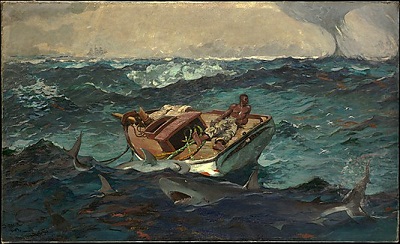

Winslow Homer, The Gulf Stream, 1899, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906, accession number: 06.1234

Winslow Homer, The Gulf Stream, 1899, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906, accession number: 06.1234

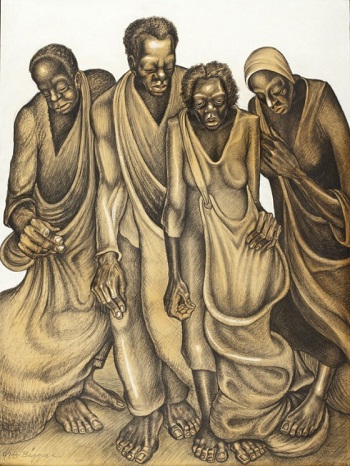

Not that there were no captivating images of blacks painted by white and black painters that reek of pathos and sentimentality. I was always struck by Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream, with a black man shipwrecked on a rudderless and sail- less boat in a stormy sea, circled by sharks with a distant ship on the horizon, which was shown in LACMA’s 2010 exhibition American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765–1915. This is an abiding metaphor. There would be beautiful renderings by Joshua Reynolds's Study of a Black Man, or John Biggers’s Cotton Pickers, or the divinely colorful Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Bashi-Bazouk, and of course a legion of work-related paintings that sadly reinforce the condition of blacks’ status: servitude.

John Anansa Thomas Biggers, Cotton Pickers, 1947, LACMA, purchased with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Thomas H. Crawford, Jr. and the Black Art Acquisition Fund

John Anansa Thomas Biggers, Cotton Pickers, 1947, LACMA, purchased with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Thomas H. Crawford, Jr. and the Black Art Acquisition Fund

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Bashi-Bazouk, 1868–69, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2008, accession number: 2008.547.1

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Bashi-Bazouk, 1868–69, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2008, accession number: 2008.547.1

The power of the imagery by this endearingly charming man, Robert Mapplethorpe, filled with honest warmth and a sensuous admiration was to free the black male from the shackles of invisibility as this shadowy dark otherness of the so-called American Dream by the very means it was feared: a full-frontal revelation of his maleness. In the exhibition, the stellar beauty of the flowers counterbalance the metallic grays of skin, bone, and muscle restlessly exchanged as classic poetic forms. Like hot ice, Mapplethorpe burns coolness into the image possibly in an effort to capture the ecstatic realism that was before him. Homosexuality, combined with sadomasochistic leather/chain garb, reinforces a shared profound otherness of the black male; and yet in an odd way, it releases a whole society of the hitherto unseen but with a deeply felt presence. Not only is it in-your-face art, but it pulls from its dubious depth an intrinsic beauty.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Jim, Sausalito (X Portfolio), 1977, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Jim, Sausalito (X Portfolio), 1977, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, partial gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the David Geffen Foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust, 2011, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The black-and-white film that the buttery Hassleblad lens enhances brings a luscious tactility to the black skin and the deep encroaching shadows, as if of some mystical nature, the chiaroscuro intrinsically ethereal and base, soft and hard, and made visible our physical subterranean worlds. XYZ, by Mapplethorpe’s own stated intention was not meant for everyone. For me, these portfolios are about an art through a portal of pleasure and pain. But art this raw, this free, was a Pandora’s Box of “the sacred and the profane” that, once opened, would change everything.

Hylan Booker