What would it have been like to grow up as an artist in pre- and post-World War I Germany? To discover the new German and international avant-garde in exhibitions and galleries, to frequent the intellectual and artistic circles in the cafés and cabarets in Germany’s capital? The young artist Hans Richter experienced the frenetic cultural life of Berlin before World War I put an end to it. He survived the war, deeply marked by its horrors which he expressed in his works of the time, then became involved with the Dadaists in Zurich, and later worked with Constructivist artists in Berlin. The exhibition Between Art and Politics: Hans Richter’s Germany presents the artistic milieus and movements Richter was involved in before, during, and after World War I. It accompanies the major retrospective Hans Richter: Encounters (opening May 5), which LACMA is dedicating to this fascinating artist—a true pioneer of modern art who was involved in virtually all the major avant-garde movements of the twentieth century: Expressionism, Dadaism, Constructivism, Surrealism, and more.

Hans Richter, Arbeiter (Workers), 1913, oil on canvas, private collection, © 2013 Hans Richter Estate

Hans Richter, Arbeiter (Workers), 1913, oil on canvas, private collection, © 2013 Hans Richter Estate

Between the –Isms: Artistic Life in Germany before World War I

The life of Richter before the war must have been exalting: Berlin, Dresden, and Munich were centers of the avant-garde, including the Expressionists of Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). These artists broke with academic modes dominant among established artists including German Impressionist Max Liebermann, and they saw themselves as rebellious visionaries. Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, cofounders of Der Blaue Reiter, tended in their works toward abstraction, exploring the inherently spiritual aspects of color. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel of Die Brücke found inspiration in the German woodcut and non-Western cultures. Besides Expressionism, French art was dominating the German art scene. Paul Cézanne, regarded as a precursor to Cubism, became a major source of inspiration for young artists, including Richter. He and his contemporaries were struck by a sort of “musical rhythm” they saw emerging from Cézanne’s works, and they started to experiment with the decomposition of form itself.

Paul Cézanne, The Bathers, c. 1898, color lithograph, Dr. Dorothea Moore Bequest

Paul Cézanne, The Bathers, c. 1898, color lithograph, Dr. Dorothea Moore Bequest

Hans Richter, Music, c. 1916, linoleum cut on wove paper, published in Die Aktion, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, purchased with funds provided by Anna Bing Arnold, Museum Associates Acquisition Fund, and deaccession funds, © 2013 Hans Richter Estate

Hans Richter, Music, c. 1916, linoleum cut on wove paper, published in Die Aktion, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, purchased with funds provided by Anna Bing Arnold, Museum Associates Acquisition Fund, and deaccession funds, © 2013 Hans Richter Estate

While exhibitions presented the works of major artists, galleries and periodicals became a platform for the new generation; the journal Der Sturm (The Storm), published by Herwarth Walden, gave voice to a varied range of young painters, writers, and poets. Walden’s Galerie Sturm in Berlin similarly showcased young German and foreign artists, such as Georg Muche, the Austrian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka, and the American Albert Bloch, and also introduced Futurism to the German art world. Die Aktion (The Action), a left-wing literary magazine published by Franz Pfemfert, featured the artworks of many Expressionists and politically involved artists, among them Hans Richter.

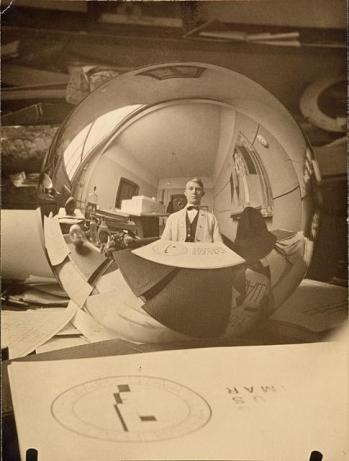

Georg Muche, Self-Portrait, c. 1920, gelatin-silver print, The Audrey and Sydney Irmas Collection, © Georg Muche Estate

Georg Muche, Self-Portrait, c. 1920, gelatin-silver print, The Audrey and Sydney Irmas Collection, © Georg Muche Estate

In Times of War and Revolution

But then the war came. When World War I (1914–18) broke out, numerous artists embraced the patriotic idea of fighting for their homeland. Many of them quickly became disillusioned with the war and ideological militarism.

Conrad Felixmüller, Soldier in a Madhouse (Soldat im Irrenhaus), 1918, lithograph printed in red and blue-violet on laid paper, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © Conrad Felixmüller Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

Conrad Felixmüller, Soldier in a Madhouse (Soldat im Irrenhaus), 1918, lithograph printed in red and blue-violet on laid paper, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © Conrad Felixmüller Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

Richter was enlisted but was wounded a few months later and was discharged from service. He lost his younger brother on the front and many of his fellow artists were killed, among them Franz Marc and August Macke. Those who survived were hoping for a better and more equal society and many became actively involved in politics; some associated with Marxist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, founders of the Spartacus League. Richter, along with other artists, associated with the communist government in Munich, which had succeeded the Bavarian Council Republic.

Julius Ussy Engelhard, Bolschewismus bringt Krieg, Arbeitslosigkeit und Hungersnot (Bolshevism Brings War, Unemployment, and Famine), 1918, lithograph printed in red, yellow, brown, and black on wove paper, Gift of the Robert Gore Rifkind Collection, Beverly Hills, CA, © Julius Ussy Engelhard Estate

Julius Ussy Engelhard, Bolschewismus bringt Krieg, Arbeitslosigkeit und Hungersnot (Bolshevism Brings War, Unemployment, and Famine), 1918, lithograph printed in red, yellow, brown, and black on wove paper, Gift of the Robert Gore Rifkind Collection, Beverly Hills, CA, © Julius Ussy Engelhard Estate

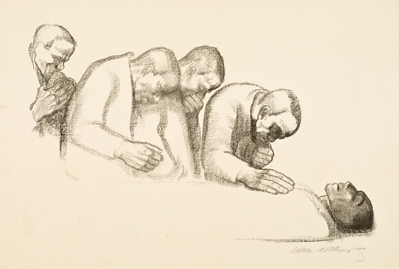

But the revolutionary spirit was soon brought down: Liebknecht and Luxemburg were murdered in January 1919 by the Freikorps, a German paramilitary organization. And in May the revolution in Munich was crushed. The murders and the extreme violence which reigned in Germany were echoed in works of artists, such as Käthe Kollwitz, who was not a communist but expressed sorrow in the face of death and a longing for a better world in her prints.

Käthe Kollwitz, Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht (Commemorative Print for Karl Liebknecht), 1919, lithograph on heavy Papier Lipsia, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © Käthe Kollwitz Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

Käthe Kollwitz, Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht (Commemorative Print for Karl Liebknecht), 1919, lithograph on heavy Papier Lipsia, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © Käthe Kollwitz Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

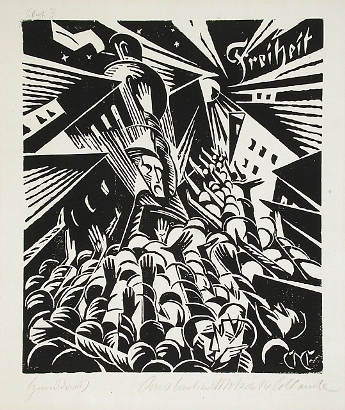

The Faith in a New Society

The desire for social reform was expressed in an almost religious way by some of Richter’s contemporaries, who saw the revolution as the dawn of a new age of freedom.

Constantin von Mitschke-Collande, Freiheit (Freedom), 1919, woodcut on laid paper, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © Constantin von Mitschke-Collande Estate

Constantin von Mitschke-Collande, Freiheit (Freedom), 1919, woodcut on laid paper, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © Constantin von Mitschke-Collande Estate

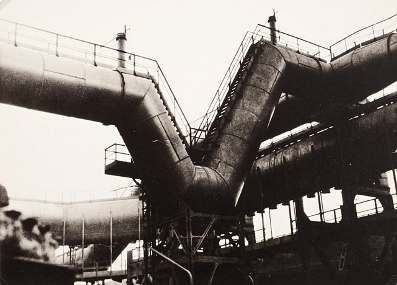

Breaking with the past, many artists rejected Expressionism as part of the old social order, and sought a new expressive potential in abstract forms, leading toward Constructivism. Others turned to a sober and direct realism that found its most notable expression in Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a movement that championed a departure from subjective interpretations and a devotion to the object. In photography, artists such as Hans Finsler, August Sander, and Else Thalemann focused on industrial buildings and workers, abandoning old aesthetic criteria to concentrate on structure and form.

Else Thalemann, Untitled (From the series Industrie Ruhrgebiet), c. 1925, gelatin silver print, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Else Thalemann Estate

Else Thalemann, Untitled (From the series Industrie Ruhrgebiet), c. 1925, gelatin silver print, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Else Thalemann Estate

Although this exhibition is only meant to give an overview, the works on view illustrate the exceptional richness of artistic life in Germany in the first decades of the twentieth century, diminished by the war but rebuilt from ashes, and contribute to a better understanding of today’s society and art.

Frauke Josenhans, Curatorial Assistant, Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies