Opening this Sunday is James Turrell: A Retrospective—a large-scale survey of Turrell’s career filling galleries in both BCAM and the Resnick Pavilion. Michael Govan, LACMA’s Wallis Annenberg Director, serves as co-curator of the exhibition along with contemporary art curator Christine Y. Kim. Below is an excerpt from Govan’s essay “Inner Light,” found in full in the accompanying exhibition catalogue co-published by LACMA and DelMonico Books/Prestel.

James Turrell, Afrum (White), 1966, Cross Corner Projection, LACMA, partial gift of Marc and Andrea Glimcher in honor of the appointment of Michael Govan as CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director and purchased with funds provided by David Bohnett and Tom Gregory through the 2008 Collectors Committee, © James Turrell, photo © 2013 Museum Associates LACMA

James Turrell, Afrum (White), 1966, Cross Corner Projection, LACMA, partial gift of Marc and Andrea Glimcher in honor of the appointment of Michael Govan as CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director and purchased with funds provided by David Bohnett and Tom Gregory through the 2008 Collectors Committee, © James Turrell, photo © 2013 Museum Associates LACMA

The theme of light has preoccupied artists for centuries. Leonardo da Vinci wrote volumes about the importance of light in rendering nature; Romantic artists described the sublime through light; and others, from Russian icon painters to modern artists, used abstract forms to account for a divine or inner light. No one, however, has so fully considered the “thingness” of light itself—as well as how the experience of light reflects the wondrous and complex nature of human perception—as James Turrell has more than four decades. As the artist himself explains of his work, “Light is not so much something that reveals as it is itself the revelation.”

During the 1960s, Turrell emerged as one of the most radical of a new generation of artists. At a moment when American art in particular was dealing with extremely simplified forms (which were the beginnings of Minimalism), Turrell applied this approach to nothing—no object, only light and perception. His earliest light projections and constructions conjure a material perception of the immaterial, and in his (still unfinished) magnum opus, Roden Crater, Turrell goes beyond even that. One of the most ambitious artworks ever conceived, representing forty years of ongoing work to convert an extinct volcanic crater in northern Arizona, Roden Crater—through light—conveys the vastness of the cosmos within the tangible space of human experience.

James Turrell, Roden Crater Project, view toward northeast, photo © Florian Holzherr

James Turrell, Roden Crater Project, view toward northeast, photo © Florian Holzherr

By devising means to hold light as an isolated and almost tactile substance, Turrell has created opportunities for us to experience it as a primary physical presence rather than as a tool through which to see or render other phenomena. Viewing his work, we are called upon not to consider what is being lit but instead to contemplate the nature of the light itself—its transparency or opacity, its volume, and its color, which is often perceived as changing, thus adding a temporal aspect to the experience. Turrell’s work is especially “modern” in this sense. So often it is presumed that the most revolutionary aspect of (Western) modern art is a tendency toward abstraction or intellectualization, accompanied by a distancing of emotion. But quite the opposite is true: as Cubism offers multiple points of view at once; as Color Field Painting and Hard Edge Abstraction isolate visual phenomena through distinct color and form; as Abstract Expressionism allows the materiality of paint or canvas to dominate composition or subject; as Surrealism excavates the unconscious and brings it to the surface; as Conceptualism can provide more direct access to the artist’s intentions; and as photography has often concerned itself with verisimilitude, much modern and contemporary art strives to heighten awareness of our own perception and understanding more than artworks based on conventional narrative, symbolic, or illustrative structures. Turrell’s Skyspaces—essentially rooms with apertures that open to the sky—afford the immediacy of pure color and light without the distractions of image or even paint, dramatizing the materialization of our own perception characteristic of modern art as they magically bring the sky we take for granted as being far away into our intimate physical space. There could be no better illustration of art’s capacity to put an otherwise distant truth directly in front of us than the heroic gesture of bringing the sky down to earth for our immediate consideration. Turrell closes the gap between the thing perceived and the perceiving being as he plays with the very act of seeing itself.

James Turrell, Twilight Epiphany, 2012, A James Turrell Skyspace, the Suzanne Deal Booth Centennial Pavilion, Rice University, Houston, TX, © James Turrell, photo © Florian Holzherr

James Turrell, Twilight Epiphany, 2012, A James Turrell Skyspace, the Suzanne Deal Booth Centennial Pavilion, Rice University, Houston, TX, © James Turrell, photo © Florian Holzherr

Of course, removing the distance between the perceiver and the object perceived in order to see “truth” is an ongoing concern, if also an elusive concept. This “problem of objectivity” is one of the great themes of both modern art and twentieth-century philosophy. Even in the nascent Modernism of late nineteenth-century French painting—the often dimly lit but shocking realism of Gustave Courbet’s studio-based practice on one hand and the intense reality of pure color and light of the Impressionists’ plein air painting on the other—one senses those artists’ interests not only in what is seen but also in how it is seen, and in what context. Courbet’s realism stripped away the artifice of artistic description in search of the social and political truths of his day. The Impressionists, anticipating Turrell’s interests a century before, opened the door to understanding that our perception of “reality” is dependent on the medium of light, which is a reality in itself. Claude Monet’s huge water lily paintings paved the way for the American Abstract Expressionists’ efforts much later to disassociate the facts of paint, color, and light from any particular referent in the visible world in favor of a visceral formal coherence that often attempts to fill the entire field of one’s vision. More recently, installation art immerses the viewer entirely in its own visual context. “Removing the frame” from a picture or creating the entire “frame of reference” for a visual experience is evidence of artists’ growing awareness of the idea that what is seen depends on the context in which it is seen and the mechanism that facilitates vision.

James Turrell, Bridget’s Bardo, 2009, Ganzfeld, installation view at Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany, 2009, © James Turrell, photo © Florian Holzherr

James Turrell, Bridget’s Bardo, 2009, Ganzfeld, installation view at Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany, 2009, © James Turrell, photo © Florian Holzherr

Today we understand that knowledge depends on perspective—that is, the circumstances through which it is attained—and that perception is not fixed. Historically, however, this was not always the case. Renaissance artists utilized color for its symbolism and to enhance the naturalism of their compositions, and in the seventeenth century, Sir Isaac Newton defined the optical spectrum of color in terms of absolute and universal wavelengths of visible light. A radical shift occurred when Johann Wolfgang von Goethe responded to Newton in the eighteenth century with a theory of color based on observation and the experienced (rather than the externally measurable) qualities of phenomena as they are received. In the early to mid-twentieth century, Josef Albers demonstrated in both his teaching and painting that our perception of color is entirely dependent on the context within which we see it. Turrell deploys that same principle in his Skyspaces to make the wide open sky appear to turn red or green or any other color he chooses. Visible form is subject to the same relativity. A particularly surprising moment in the experience of Roden Crater happens when visitors climb a tunnel several hundred feet long toward its open terminus, a circular disc of light; as a viewer approaches, he or she perceives the disc transform slowly into a highly elongated ellipse, not a circle at all, and may recall that an ellipse can easily be perceived as a perfect circle when viewed from a certain vantage point.

Turrell’s formal theatrics aim not to deceive but to reveal. Never do we see the world with entirely open and unbiased eyes; the preconditions of our seeing and understanding are an ever-present influence on our vision. The brilliant astronomer Copernicus was limited in trying to reconcile his experience of planetary motion into circular orbits due to assumptions dating back to the time of Aristotle that the universe is perfect and therefore would express itself in the perfect geometry of a circle. These assumptions were upended by Johannes Kepler, who understood that a circle is only a manifestation of an ellipse, which in turn defines planetary orbits. The circle is essentially a geometric subset, an ellipse with its two foci coexistent.

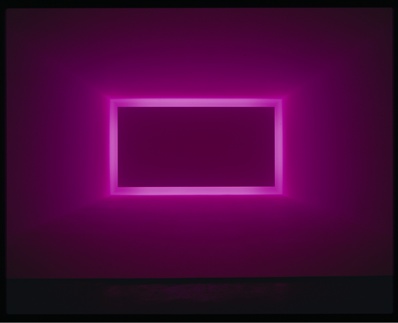

James Turrell, Raemar Pink White, 1969, Shallow Space, collection of Art & Research, Las Vegas, © James Turrell, photo by Robert Wedemeyer, courtesy Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles

James Turrell, Raemar Pink White, 1969, Shallow Space, collection of Art & Research, Las Vegas, © James Turrell, photo by Robert Wedemeyer, courtesy Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles

Turrell’s art does not illustrate these leaps in understanding but embodies them. The actual experience of light in Turrell’s constructions often defies our expectations—whether it is seeing a circle reveal itself as an ellipse or wondering how the world outside a Skyspace can seem from inside as if it has been painted a deep shade of blue or red or green. These experiences prompt us to consider the nature of our own perceptual apparatus as much as the thing we are perceiving. This is by design. In fact, the artist has said that perception is his true medium. The greatest revelations borne by Turrell’s art are a deeper understanding of what it is to be a perceiving being and an awareness of how much of our observation and experience is illuminated by the “inner light” of our own perception. Turrell often refers to the brilliance of color experienced in a lucid dream when the eyes are closed—or to the Quaker practices of his religious upbringing, which describe meditation as “going inside to greet the light.” The Quaker concept of “inner light,” which is shared in a collective silent-prayer meeting, is echoed in the experience of Turrell’s Skyspaces—in the collective silence, duration, and receptivity they induce.

Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director