In planning The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA, we decided to begin our story with the famed La Brea Tar Pits. While it may seem unusual to start an architectural history in the Ice Age, we were inspired by Zumthor’s deep investigation of his project sites. We soon found that LACMA’s unique location has impacted its buildings almost from the very beginning.

William L. Pereira and Associates. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, c. 1965. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

William L. Pereira and Associates. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, c. 1965. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

In March 1965 LACMA opened the doors to its three William Pereira-designed pavilions amid great civic celebration. Newly separated from the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art, the art museum—hailed as the “largest ever to be built west of the Mississippi”—represented L.A.’s emergence as a cultural capital. The opening night fireworks were reflected in the man-made lake that surrounded the structures; one reviewer described the structures as “set like a gleaming white island in the shimmering pool of water.”

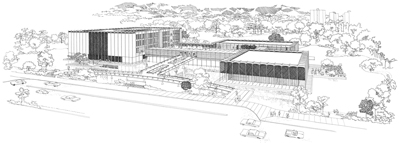

Carlos Diniz for William L. Pereira and Associates. Early rendering for Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1960. Offset print on paper of pen-and-ink drawing. Courtesy Carlos Diniz Family Collection and Edward Cella Art+Architecture

Carlos Diniz for William L. Pereira and Associates. Early rendering for Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1960. Offset print on paper of pen-and-ink drawing. Courtesy Carlos Diniz Family Collection and Edward Cella Art+Architecture

The water was central to Pereira’s concept for the site, showing up in early renderings (such as this 1960 depiction by master delineator Carlos Diniz). As the architect envisioned it, “The restful splashing of the fountains block out the noise of the traffic, and the surrounding pools of water set the museum apart visually from the activities on the boulevard.” This plan echoed recent trends in civic architecture, drawing comparisons to New York’s Lincoln Center and the Music Center that had opened a few months earlier in downtown Los Angeles.

William L. Pereira and Associates. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, c. 1965. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

William L. Pereira and Associates. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, c. 1965. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

Within months of the opening, however, the inherent flaws in the architect’s idyllic vision began to quite literally bubble to the surface. By October 1966, the board of trustees was already concerned about “highly inflammable gas” in the east pool, noting that they had drained the water four times in the previous five weeks. While Pereira’s planning documents acknowledge that the tar pits required special consideration, he didn’t anticipate all of the ways that this would affect his design. Soon, the board began to consider replacing the problematic pond with a high-end restaurant, with some arguing that “water can be eliminated without aesthetically damaging the property.”

Concrete breaking, 1974. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

Concrete breaking, 1974. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

Despite this, the pools remained in place for nearly a decade. In 1974, the museum announced that the grounds would become a sculpture garden, and that June they hosted what they called a “concrete breaking” on the original plaza. In an interview, the chairman of the board of trustees declared “This is an instance of necessity being the mother of invention,” calling the fountains “an attractive nuisance” and noting that in addition to the issues related to the tar pits, the pools attracted litter and used 1,500 gallons of water a day.

B. G. Cantor Sculpture Garden, 1975. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

B. G. Cantor Sculpture Garden, 1975. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

The design by local landscape architect Howard Troller, highlighted nine Rodin bronzes from Cantor alongside works by modernist masters such as Alexander Calder, Henry Moore, David Smith, and John Mason.

B. Gerald Cantor Sculpture Garden, 1975. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

B. Gerald Cantor Sculpture Garden, 1975. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

Newspapers noted that the 3-acre garden included 23,000 feet of walkways, 107 new trees, and a spiral staircase by architect Craig Elwood.

B. Gerald Cantor Sculpture Garden, 1975. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

B. Gerald Cantor Sculpture Garden, 1975. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives

The 1975 garden represented major change to the campus, but beginning in the early 1980s, a series of additions were built to address the space constraints and circulation issues of the original campus. The sculpture garden has evolved along with buildings, as different artists and architects (most recently Robert Irwin) have addressed the connections between the museum, the tar pits, the park, and the entrance on Wilshire Boulevard.

Installation view, The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA

Installation view, The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA

Zumthor’s proposal explores new ways to integrate the park and the museum—opening up walkways through the campus and making artworks inside of the “park-level” cores visible from outside—continuing the longstanding conversation of how to unify the many elements of this important but challenging site.

Staci Steinberger, Curatorial Assistant, Decorative Arts and Design