Under the moniker of Temporary Travel Office, artist Ryan Griffis engages touristic spaces in new ways; he has developed an emergency tourism kit for a city in Norway, and established an embassy for a watershed in Cleveland, among other projects. Recently, we invited him to create something for our website, inspired by a work of his choosing; Becoming Movable is his response to the Fireplace Surround from the Patrick J. King House in Chicago, which is on view in our American art galleries.

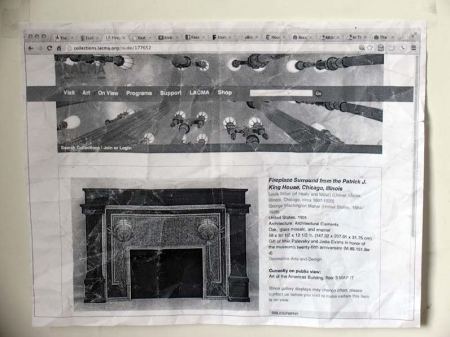

Louis Millet (of Healy and Millet), Fireplace Surround from the Patrick J. King House, Chicago, Illinois, 1901, gift of Max Palevsky and Jodie Evans in honor of the museum's twenty-fifth anniversary

Louis Millet (of Healy and Millet), Fireplace Surround from the Patrick J. King House, Chicago, Illinois, 1901, gift of Max Palevsky and Jodie Evans in honor of the museum's twenty-fifth anniversary

In researching the history of the fireplace, Griffis uncovered ephemera that contributed to our knowledge of its provenance. (A link to Becoming Movable is now part of the record for the fireplace mantle on our new collections website.)

Screen capture from Becoming Movable

Screen capture from Becoming Movable

Here is what Ryan had to say about the project:

How did you select the fireplace surround? Where did your investigation lead you?

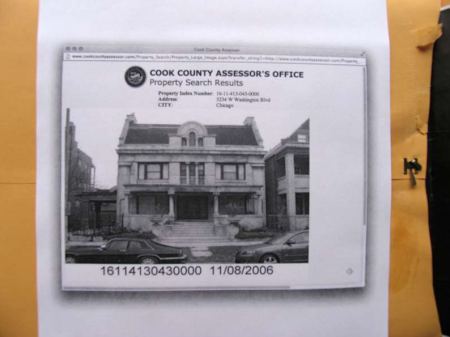

Griffis: It stood out as an odd kind of object to me. The house (now known as the King-Nash House) that it was designed for is not far from me. The neighborhood, East Garfield Park, just west of downtown, has been devastated by economic and political abandonment that began before World War II. The house became an official city landmark close to the same time that the fireplace surround was acquired by LACMA. How did a fireplace from such a notable house in Chicago’s west side end up in a museum in Los Angeles?

There was no readily available answer to this question. I started by contacting some local architectural experts, combing through archives in the Public Library, and searching online. Eventually, this led me to the current owner of the house. It turns out, maybe unsurprisingly, that there were several fireplaces in the house and many other architectural details that all became “independent” objects around the same time. The house, during an extended period of abandonment, was essentially gutted of the details Maher is known for. Scrappers sold these objects to architectural salvage and antique dealers, who in turn sold them (for a much higher amount, one can assume) to collectors and institutions. Through this transaction, these objects became “movable property,” distinct from the “real property” of the King-Nash House and the land it sits on.

Screen capture from Becoming Movable

Screen capture from Becoming Movable

I became fascinated by a duality of property as both material and discourse. The documents that identify property out of otherwise undifferentiated things are also material things that take up space and have to be maintained, whether that space is occupied by file cabinets or computers. Our reality is tied to both and renders them inseparable in many ways.

In your online project, you point out that the fireplace surround, both as an object and as an image, has dimensions that are comparable to the 4:3 aspect ratio which would become the standard for the television industry in the 1930s. How did you arrive at this realization?

Griffis: I happened on this realization while sketching out some initial ideas I was using the dimensions of the opening in the fireplace (based on the image on LACMA’s website) as a template for scaling other images and video. In doing so, it became apparent that the aspect ratio was extremely close to that for standard definition NTSC video. It’s not really that odd, considering that the 4:3 ratio (1.33:1) is close to classical proportions, the “golden section,” etc., but it did become a narrative link that usefully bridged a few different threads of my research. I was considering architecture as media, especially Maher’s aesthetics of rhythm, and thinking about this fireplace as a kind of portal through which I was experiencing otherwise unrelated histories.

You amassed a small archive for the fireplace surround. Are there any stories from your adventures researching it that you would like to share?

Griffis: The first thing I always appreciate when doing a project like this one is the generosity of people in sharing their experience and knowledge: in this case, Kathy Cummings (architectural historian and expert on Maher); Donald Aucutt (publisher of Geo. W. Maher Quarterly); Tim Samuelson (Cultural Historian for the City of Chicago); and Vernon W. Ford, Jr. (attorney and current owner of the house) were all especially helpful.

One unexpected thing that I came across in the special collections of the Harold Washington Library was a book about Fifth City, a smaller neighborhood within East Garfield Park. The name Fifth City originated with a utopian community development project that started in the early 1960s and lasted for about a decade, led by a Christian organization called the Ecumenical Institute, which is affiliated with the Institute for Cultural Affairs. It gained some recognition for its early success building of schools and making residential improvements, but seemed doomed in the face of continuing, and violent, racial and economic segregation. I’ve talked to people who have been in the city for a long time and have an interest in community organizing and radical movements, and they knew nothing about this history. Fifth City is only briefly mentioned in the project (through a couple of images from the book), as it’s a bit of a tangent, but it’s something I’m looking forward to researching and learning more about.

Becoming Movable is part of our ongoing Artists Respond series of web-based projects taking as a point of departure a work of art on view at LACMA. Find out more.

Joel Ferree