When looking at a work of art for the first time, I often ask the following questions: What is the artist trying to communicate? How is the work reflective of society? Perhaps this tendency to wax philosophic about how a piece fits into the bigger picture (my apologies—no pun intended) can be chalked up to my background studying political science and human rights. I'm always trying to dissect larger issues.

For me, it is important to ask these questions to enhance the art-viewing (and comprehension) process. After all, something had to inspire the artist to create the work in the first place. It would only illuminate our understanding of a piece to try to figure out if its making was related to a larger issue of their time. While not every work can be attributed to a broad social concern—artists do have personal experiences and motivations to draw from, of course—I believe it’s fair to assert that many works do reflect and make a statement about something greater and serves as a medium for social commentary.

With that in mind, I will look at specific pieces that captured my attention while combing the relationships between objects and society. Particularly notable, in my opinion, are the assemblages of Edward Kienholz.

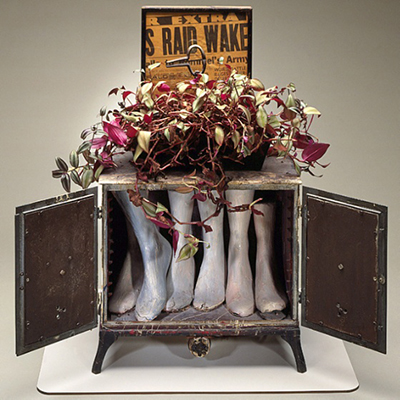

Edward Kienholz, A Lady Named Zoa, 1960, gift of Mrs. Lillian Alpers, © Keinholz

Edward Kienholz, A Lady Named Zoa, 1960, gift of Mrs. Lillian Alpers, © Keinholz

In his haunting sculptures from the 1960s, Kienholz clearly alludes to emerging widespread concerns of his time—and, arguably, of our time as well. The boxes forming the body of A Lady Named Zoa, for example, can be said to represent the limits that society places on women, reinforcing the commonly held ideals of what is “acceptable.” Also addressing a question of women’s rights, The Illegal Operation depicts the controversy surrounding abortion. (This was, in fact, a personal issue for Kienholz, as his then-wife underwent an illegal-at-the-time procedure herself.) History as a Planter reflects on Holocaust remembrance.

Edward Kienholz, The Illegal Operation, 1962, partial gift of Betty and Monte Factor and purchased with funds provided by the Art Museum Council, Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, the Modern and Contemporary Art Council, Dallas Price-Van Breda and Bob Van Breda, the Robert H. Halff Fund, David G. Booth and Suzanne Deal Booth, Virginia Dwan, Elaine and Bram Goldsmith, The Grinstein Family, Ric and Suzanne Kayne, Alice and Nahum Lainer, Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Mrs. Harry Lenart, The Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Philippa Calnan and Laura Lee Woods, © Keinholz

Edward Kienholz, The Illegal Operation, 1962, partial gift of Betty and Monte Factor and purchased with funds provided by the Art Museum Council, Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, the Modern and Contemporary Art Council, Dallas Price-Van Breda and Bob Van Breda, the Robert H. Halff Fund, David G. Booth and Suzanne Deal Booth, Virginia Dwan, Elaine and Bram Goldsmith, The Grinstein Family, Ric and Suzanne Kayne, Alice and Nahum Lainer, Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Mrs. Harry Lenart, The Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Philippa Calnan and Laura Lee Woods, © Keinholz

Edward Kienholz, History as a Planter, 1961, anonymous gift through the Contemporary Art Council, © Keinholz

Edward Kienholz, History as a Planter, 1961, anonymous gift through the Contemporary Art Council, © Keinholz

Some artists, however, view in a different light their potential role as recorders and interpreters of social issues. Take the words of José Clemente Orozco, known—along with Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros—as one of “Los Tres Grandes” (The Big Three) of Mexican muralists: straying from the political and propagandistic leanings of the works of his counterparts, Orozco notably stated, “A painting should not be a commentary, but the fact itself.”

José Clemente Orozco, Street Corner, Brick Building (Esquina, edificio de ladrillo), 1929, purchased with funds provided by the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund, © Artist Right Society (ARS)

José Clemente Orozco, Street Corner, Brick Building (Esquina, edificio de ladrillo), 1929, purchased with funds provided by the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund, © Artist Right Society (ARS)

Examining that statement in the context of Orozco’s Street Corner, Brick Building (Esquina, edificio de ladrillo), the depiction of Manhattan becomes not one of sheer symbolism, but rather an objective reflection of the urban center known for its symbolic role as a beacon of modernity, becoming a form of the “New Art” that Orozco believed was an integral part of an ever-evolving America.

It can be said, however, that social commentary and fact are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Directly rooted in Los Angeles history, Matta’s Burn, Baby, Burn (L’escalade) is a prime example of a balance between the two.

Matta (Roberto Sebastián Antonio Matta Echaurren), Burn, Baby, Burn (L'escalade), 1965–66, gift of the 2009 Collectors Committee with additional funds provided by the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund, © Roberto Matta Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Matta (Roberto Sebastián Antonio Matta Echaurren), Burn, Baby, Burn (L'escalade), 1965–66, gift of the 2009 Collectors Committee with additional funds provided by the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund, © Roberto Matta Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

First inspired by the atrocities of the Vietnam War, the painting evolved into a reflection of the violence of the 1965 Watts riots. The mural-sized painting captures the nature of the violence, while, as noted by LACMA curator Ilona Katzew, “the phosphorescent, pungent green at the bottom right of the composition suggests hope, a verdant future,” thus adding a touch of Matta’s personal interpretation of the situation to the work.

Looking at the different degrees of social commentary in the works of these three artists—not to mention the infinitely varying degrees of other artists—we can see that their interpretation of what role they play in shaping societal issues varies just as much as the issues (if any) that they choose to take up.

Sara Hupp, intern