In his 1915 novel The Golem, Austrian novelist Gustav Meyrink wrote, “Who can say he knows anything about the Golem? . . . Always they treat it as a legend, 'til something happens and turns it into actuality again. After which it’s talked of for many a day.” Meyrink is speaking to the eternal nature of the golem myth. This timeless quality is evidenced in the use of the golem figure in contemporary art and pop culture.

Paul Wegener and Carl Boese (directors), film still from Der Golem: Wie er in die Welt kam (The Golem: How He Came into the World), 1920, written by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen, produced by Paul Wegener

Paul Wegener and Carl Boese (directors), film still from Der Golem: Wie er in die Welt kam (The Golem: How He Came into the World), 1920, written by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen, produced by Paul Wegener

The most well-known golem narrative, which formed the basis for Paul Wegener’s 1920 film Der Golem: Wie er in die Welt kam (The Golem: How He Came into the World), is set in 16th-century Prague, where a cruel emperor persecutes Jewish residents. Rabbi Loew fashions the golem from riverbed clay and brings him to life with a mystical amulet; the creature then rampages through the city, crushing the enemies of the Jews. As the monster begins to experience glimmers of human emotion in the aftermath of destruction, he is disabled when a little girl removes the amulet. According to legend, the golem still lies dormant in Prague’s oldest synagogue, perhaps to be reanimated one day.

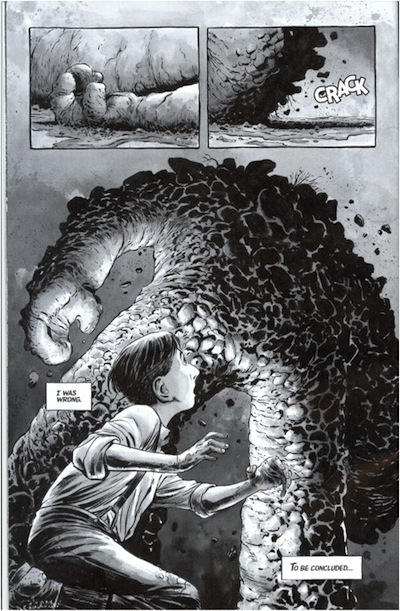

Dave Wachter (artist), Steve Niles, and Matt Santoro (writers), page from Breath of Bones: A Tale of the Golem, no. 2 (July 2013), private collection, Los Angeles, © 2013 Steve Niles, Matt Santoro, & Dave Wachter

Dave Wachter (artist), Steve Niles, and Matt Santoro (writers), page from Breath of Bones: A Tale of the Golem, no. 2 (July 2013), private collection, Los Angeles, © 2013 Steve Niles, Matt Santoro, & Dave Wachter

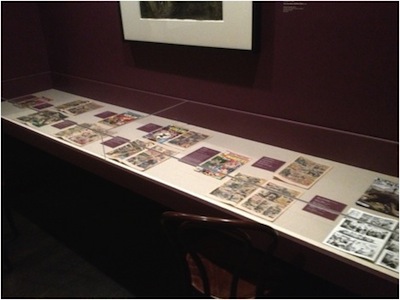

The idea of a magical creature with immense strength and power created to protect the innocent is at the heart of many superhero stories. It is no wonder then that the golem has been a character in numerous comic books. For instance, three 1974 issues of Marvel’s Strange Tales feature the golem. In this story, the golem, created and brought to life in the middle ages, was subsequently buried in sand and forgotten. The figure is then excavated by professor Abraham Adamson and reanimated as he dies to protect his family. Although the golem is dangerous, he is ultimately driven by the professor’s love for his family. In a 1977 issue of The Invaders, also published by Marvel, the golem comes to the heroes’ rescue when they are held by Nazi scientists. In this fiction, kabbalah scholar Jacob Goldstein, who lives in the Warsaw ghetto, is supernaturally merged with clay to become the golem to defeat the Nazis holding the Invaders, eventually destroying the walls of the ghetto. The transformation of Goldstein inspires him to lead a rebellion.

Comic-book installation in the exhibition Masterworks of Expressionist Cinema: The Golem and its Avatars, in the Ahmanson Building, Level 2, at LACMA

Comic-book installation in the exhibition Masterworks of Expressionist Cinema: The Golem and its Avatars, in the Ahmanson Building, Level 2, at LACMA

The use of the golem to protect Jewish communities from Nazi forces is beautifully depicted in the 2013 comic series Breath of Bones, illustrated by Dave Wachter and published by Dark Horse Comics. Here, in a departure from the Rabbi Loew myth, the children of the threatened village collect mud and form it into a huge human shape. After they flee, Noah, the protagonist, and his grandfather stay and pray over the golem. As Nazi troops roll into the village, Noah’s grandfather dies, but his life and their faith animates the figure and transforms him into the powerful golem. In these comic books, the legends of the golem are adapted, but the essence of it being a protective supernatural creature remains.

David Musgrave, Untitled from Reverse Golem Portfolio, 2012, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum, purchased jointly with funds provided by the LACMA Art Museum Council, the LACMA Prints and Drawing Council, and the Grunwald Center Helga K. and Walter Oppenheimer Acquisition Fund, TR.16296.1.5,

David Musgrave, Untitled from Reverse Golem Portfolio, 2012, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum, purchased jointly with funds provided by the LACMA Art Museum Council, the LACMA Prints and Drawing Council, and the Grunwald Center Helga K. and Walter Oppenheimer Acquisition Fund, TR.16296.1.5,© 2013 David Musgrave, photo courtesy Edition Jacob Samuel, Santa Monica

David Musgrave’s Reverse Golem Portfolio displays an interest in the creative act of making a golem rather than an emphasis on its mythical abilities. Musgrave is known for his trompe l’oeil depictions of crude stick figures. At first glance the humanlike figures look like they are made from scraps of paper. However, they are actually carefully rendered depictions of collage. Rather than draw the figures on the metal plates used to make these prints, Musgrave employs wide and narrow parallel lines to produce the illusion of a three-dimensional assemblage of paper. By using this labor-intensive technique and calling the figures golems, the artist emphasizes the generative act of creating. Like Rabbi Loew, Musgrave has made something vital and brimming with life out of inanimate and simple materials: clay in the case of the homunculus and lines in these prints.

These contemporary explorations of the golem myth and figure speak to the continued potency of the legend for artists.

Sienna Brown, curatorial assistant, Prints and Drawings