I recently caught a showing of John Logan’s play Red, which first premiered in London in 2009, making its debut on Broadway one year later. The performance focuses on fictional exchanges between artist Mark Rothko and his young assistant in 1958, a year when Rothko accepted a $35,000 commission to paint a number of murals for a new restaurant in New York City.

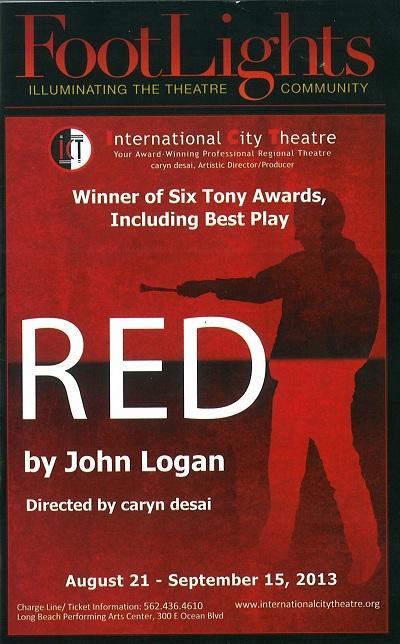

Program for Red

Program for Red

Born Marcus Rothkowitz a 110 years ago today, Mark Rothko was an émigré from Latvia who came from humble beginnings. He attended Yale University in 1921 on scholarship, only to drop out a few years later to focus on his art in New York City. After working with the Arts Students League and the Works Progress Administration (under the Federal Art Project) in the 1920s and 1930s, respectively, Rothko had achieved critical acclaim with his color-field paintings, a style of Abstract Expressionism in which works typically comprised of large, solid planes of color rendered on flat surfaces. By the time Rothko was invited to participate in the restaurant commission, his name was already well established in the Abstract Expressionist circles, which emerged in the United States and included painters such as Adolph Gottlieb, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, and others.

The commission Rothko accepted was envisioned as an “environment” of murals for the Four Seasons Restaurant in the newly built Seagram Building, a skyscraper on Park Avenue designed by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was noted for his functional modernist design. Having had created a of number murals in 1959, it is interesting to note that Rothko had abruptly cancelled the commission after the restaurant opened to the public. Reasons behind the cancellation varied, but in 1959, Rothko himself ultimately explained to his friend John Fischer, “I accepted this assignment as a challenge, with strictly malicious intentions . . . I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room . . . ” A couple of years later, Rothko’s assistant, Dan Rice, recalled Rothko saying, “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those prices will never look at a picture of mine.”

Red is a drama that offers fictional insight as to what might have been the reason Rothko quit such a hefty commission at the time. One of the more memorable exchanges in the performance is the volatile tête-à-tête (mainly by Rothko) when he asks his young assistant, Ken, “What do you see?” after looking at one of his murals. Ken's response is eponymous with the title of the play, Red. In the performance, the audience witnesses Rothko, the expert, training the novice with verbally explosive discourse in what would have been typical Rothko fashion.

After taking a walk in our galleries, it’s an appropriate question when contemplating Rothko’s White Center (1957), currently on display:

Mark Rothko, White Center, 1957, David E. Bright Bequest, © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mark Rothko, White Center, 1957, David E. Bright Bequest, © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

So now I ask you readers: what do you see?

Devi Noor, curatorial assistant