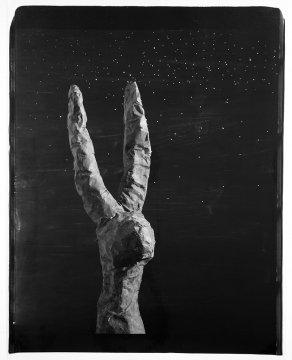

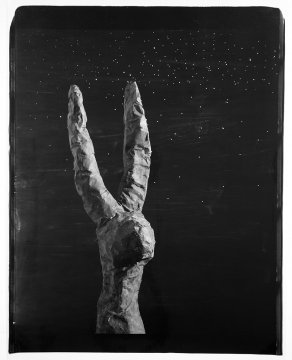

In the series 20x24 Polaroid, photographer John Divola created ersatz forms and backdrops from detritus and found materials, then photographed the carefully crafted scenes. The resulting images feature referents to familiar objects in the real world, such as the “rabbit” in Rabbit, 87RBA1.

The rabbit has the markings of a rabbit—indeed, namely its ears tell us so. The backdrop appears to be a night scene, with stars clustered and randomly spread throughout the dark sky. We perhaps assume some angle of moonlight reflects off the rabbit’s visage and large ears.

At this point, the illusion starts to break down. The shadows cast against the crumpled angles of the rabbit form confirms the deliberate artificiality of the constructed scene.

John Divola, Rabbit, 87RBA1, 1987–89, © John Divola

John Divola, Rabbit, 87RBA1, 1987–89, © John Divola

At LACMA, the exhibition John Divola: As Far as I Could Get, photographer John Divola works through questions such as the veracity of information as communicated via the camera lens, the history of photograph as examined through historical stereoscope photographs, and the photographer as performer and subject.

John Divola’s first solo museum exhibition is spread throughout three museums in the Southern California region. In addition to LACMA, John Divola: As Far as I Could Get is also being simultaneously presented at the Pomona College Museum of Art (September 3–December 22, 2013) and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (October 13, 2013–January 12, 2014).

Each of the exhibitions put on display different series from Divola's extensive oeuvre, covering the photographer's early work produced while still in graduate school at the University of California, Los Angeles (the Santa Barbara Museum of Art presentation) to his latest work, which pushes the technical elements of the photographic process while exploring issues that have been at the forefront of Divola's work in the past few decades.

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail, 1 of 36), 2002, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013, © John Divola

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail, 1 of 36), 2002, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013, © John Divola

Close looking will reveal a lot within each frame in Divola’s works in the LACMA exhibition. In the series Artificial Nature, scenes that appear like authentic, found landscapes turn out to be products of moviemaking's sleight of hand.

In the image above, the clapperboard, an object essentially synonymous with filmmaking and video production, interrupts what we perceive as a sandy beach landscape. In fact, the scene before us is so convincing that we begin to ask about what came first: was the clapperboard placed on an actual beach, or is the beach only there to conform to the production needs as guided by the clapperboard?

![1996.0009.18689 Not Known [Title not known], [Date not indicated] Keystone photo print 7.18 in. x 4.18 in. Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside Object Description: Two uniformed men on horseback surrounded by soldiers on foot with bayonets Artifact Inscription: A Bristling Forest of Bayonets, Russian Troops on Review.](/sites/default/files/attachments/1996-0009-18689.jpg) Artist unknown, A Bristling Forest of Bayonets, Russian Troops on Review, date unknown, Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

Artist unknown, A Bristling Forest of Bayonets, Russian Troops on Review, date unknown, Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

In Seven Songbirds and a Rabbit, Divola looks back at stereoscopic images, which created a three-dimensional appearance by separating viewpoints from each eye and combining them into one complete scene. The medium was popular in the 19th and early part of the 20th centuries, during which they were used as forms of entertainment and document.

Divola examines at near microscopic detail the glass-plate negatives that were used to produce stereographs. He then magnifies a detail he finds in the negatives (birds, a rabbit) to a much-larger scale (20" x 20"), printing the found details on linen. The resultant work, framed on wood and textural in its presentation, hints at the time during which these stereographs circulated.

John Divola, Seven Songbirds and a Rabbit (detail), 1995, © John Divola

John Divola, Seven Songbirds and a Rabbit (detail), 1995, © John Divola

Though likely captured by a camera in the 19th century, the songbird highlighted in this work appears dynamic and alive. The circular framing of the animal can almost be regarded as language between the photographer and the viewer. Divola tells us he spots the bird among the bigger stereograph, and he is bringing it to attention not only by frame and print, but also by contrast.

John Divola, As Far as I Could Get, (R02F33),10 Seconds, 1996–97, © John Divola

John Divola, As Far as I Could Get, (R02F33),10 Seconds, 1996–97, © John Divola

As Far as I Could Get, the titular series in LACMA's presentation, offers Divola as (literally) a distant subject. In the work, the artist captures himself running away from the camera in a 10-second sprint: the amount of time he has set the exposure for each photograph. In many ways, this series reflects themes Divola explored in both Artificial Nature and Seven Songbirds and a Rabbit. The artist uses nature as stage of sorts, performing as an actor in his own work. The camera captures his form in miniature and in nature, similar to how the songbirds were most likely lost within larger scenes of foliage within the stereographs.

At the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Vandalism (1974), a series Divola created while still in graduate school, and Forced Entry (1975) offer deeper insight into the artist's body of work, namely how it will be expressed in his Zuma series from 1977–78, 15 selections of which are on view at the Pomona College Museum of Art.

Similarly, Dogs Chasing My Car in the Desert (1995–98), a series made during a period when Divola was also working on As Far as I Could Get, shares with As Far . . . in its documentation of dynamic movement, the figure (silhouette, even) in a landscape, and a fundamental impulse in many living organisms.

These are just some of the strong connections that can be found throughout John Divola's four decades–long practice of photography. Spread throughout three museums, the multiple series on view offer an opportunity to knit together a comprehensive study of Divola's work.

Linda Theung, editor