It was a great pleasure to view the exciting LACMA exhibition Kitasono Katue: Surrealist Poet. In Japan, Kitasono Katue’s reputation as an artist, designer, and photographer has been rising exponentially in the past 10 years, despite the fact that the avant-gardist—who advocated for the amateur over the professional—was proud in the latter part of his life to pose as a minor poet. In 2010, I curated the Kitasono presentation of the exhibit, Hashimoto Heihachi and Kitasono Katue: Unusual Pair of Brothers, a Sculptor and a Poet. The exhibition ran for two months at the Mie Prefectural Art Museum (where my colleague, Mori Ichiro, curated the Heihachi presentation), after which it had a two-month display at Setagaya Art Museum in Tokyo. Although not a blockbuster—it wasn’t promoted on billboards or television like some exhibitions—the work was new to the audience and drew 14,000 visitors, many of whom were young artists, art enthusiasts, and romantic couples.

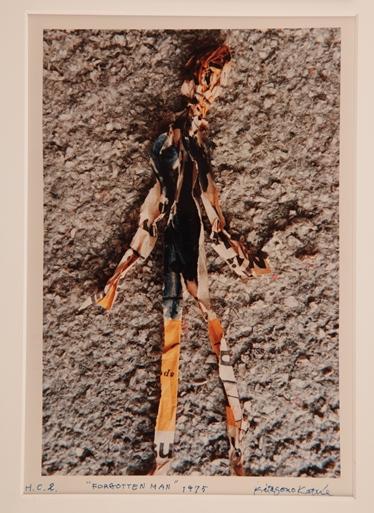

Kitasono Katue, Forgotten Man (Plastic Poem), 1975, collection of John Solt

Kitasono Katue, Forgotten Man (Plastic Poem), 1975, collection of John Solt

Over the past few years, retrospective exhibitions of artists have been held one after another, with the aim of reconsidering the careers of artists who flourished before World War II. Curators and researchers are aiming to reexamine this complex history by combining existing documents with newly discovered ones. Along with Kitasono and his brother, the lives and art of prominent figures such as Murayama Tomoyoshi (MAVO Group), Surrealist painter Koga Harue, and Nihonga-style painter Tamamura Hokuto (the sponsor of Kitasono’s Dada-era journal), among others, have added to a critical mass of a new understanding about the breadth and vibrancy of the activities of artists who worked in multiple fields and genres before the war.

There was a curious phenomenon after our exhibition: Kitasono Katue became an “idol” among young artists and art lovers—especially photographers, designers, and poets. Suddenly it became unhip to be unfamiliar with Kitasono and his works. Interestingly, this phenomenon finds a parallel to Kitasono’s popularity in the United States during the 1950–70s, when bohemian, Beat, and hippie poets were all familiar with Kitasono’s poems in English (self-translated), and later with his plastic poems.

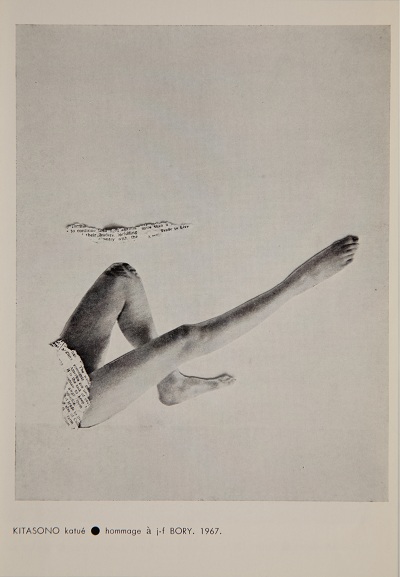

Kitasono Katue, Plastic Poem Homage to J.F. Bory (Hommage à J.F. Bory), 1967, on page 20 of the periodical VOU, no. 113, January 1968, collection of John Solt

Kitasono Katue, Plastic Poem Homage to J.F. Bory (Hommage à J.F. Bory), 1967, on page 20 of the periodical VOU, no. 113, January 1968, collection of John Solt

The recent Kitasono boom in Japan has little to do with new findings on pre–World War II artists; rather, it is linked to the contemporary art and technological worlds. There is something about the fragmental elements of Kitasono’s words and images that relates to the way information is disseminated today.

Strolling through the exhibition at LACMA, I wondered how Kitasono’s work resonates with the diverse American audience. At the partition, without curtains between the Kitasono exhibit and the permanent collection, one can stand and reflect simultaneously on two pasts: the 2,000 years represented by the priceless examples in the permanent collection, and the half-century of work by 20th-century poet-artist Kitasono Katue. It is an important and rewarding exhibition because in the one figure of Kitasono is bridged the little-known, pre-World War II Japanese avant-garde and the better-known postwar period.

Noda Naotoshi (and Mori Ichiro) flew expressly from Tokyo to see the exhibition Kitasono Katue: Surrealist Poet at LACMA. Noda and Ichiro worked collaboratively on Hashimoto Heihachi and Kitasono Katue: Unusual Pair of Brothers, a Sculptor and a Poet, which was awarded the Japanese Association of Art Museums’ 2010 exhibit of the year. Setagaya Art Museum has carved out a niche as one of the main museums in Japan for regularly displaying Japanese avant-garde art, and occasionally it also exhibits Western painting and photography. Noda recalls his experience in the LACMA presentation.

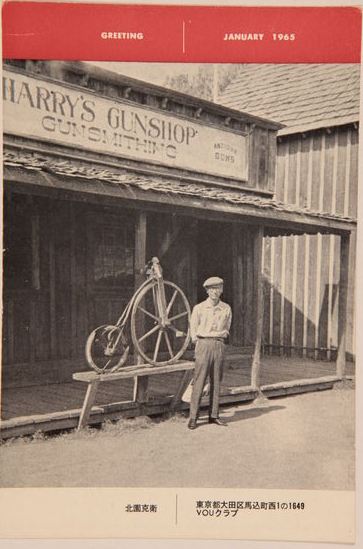

Kitasono Katue at Knott's Berry Farm in California

Kitasono Katue at Knott's Berry Farm in California

“Katue once visited the U.S. with a group of fellow librarians. He didn’t contact his literary friends—perhaps he had no time—but he made sure to have a photo of himself taken at Knott’s Berry Farm, which he made into his 1965 New Year’s greeting card and sent around.”

Noda Naotoshi, curator, Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo