Marjorie and Leonard Vernon were pioneer Los Angeles collectors who, beginning in the 1970s, amassed a group of images that covered in breadth and depth a global history of photography. See the Light—Photography, Perception, Cognition: The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection is the second major presentation (this was the first) of the Vernon Collection at LACMA since it was acquired by Wallis Annenberg and the Annenberg Foundation in 2008. In conjunction with the exhibition, Ryan Linkof and Eve Schillo organized the oral-history project. In this piece, they reflect on working with those who knew the Vernons and played a part in building their important collection. Parts of the oral-history project will be published online as part of the exhibition, and full transcripts and audio files will be available at the Balch Research Library at LACMA.

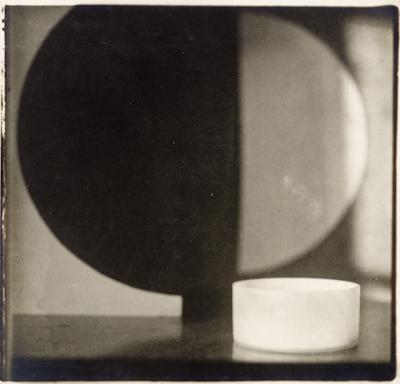

Jaroslav Rössler, Still Life with Small Bowl, 1923, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and gift of Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Jaroslav Rössler, Still Life with Small Bowl, 1923, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and gift of Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Condensed into an acronym, the Vernon Oral History Project, or the VOHP, isn’t the easiest. VOHP looks a bit off-putting—a description which, of course, was incongruous to Marjorie and Leonard Vernon, the magnanimous people behind the Vernon Collection. Add the fact that the Vernons were one of the first collectors of photography in Los Angeles—and therefore really did know everyone—and a project of this magnitude begins to sprout yet another acronym, the PNEVC, Possibly Never-Ending Vernon Circle.

In 2012 Ryan Linkof and I began our pursuit of must-have interviews relating to the Vernons, a few years after LACMA acquired the Vernon Collection in 2008 through the generosity of the Wallis Annenberg Foundation and Carol Vernon and Bob Turbin. The collection brought an amazing spotlight to the museum. It, essentially, raised the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department’s national and international profile, resulting in an increase in scholar visits and the securing of subsequent loans. We were initially kept busy with transporting, accessioning, storing, upgrading storage, digitally documenting, and reviewing over 3,500 works. After the flurry of activity, it was time to step beyond the process and to get to know the people behind this amazing collection.

Left to right: Maggi Weston, Leonard Vernon, Marjorie Vernon, photo by Rod Dresser, © Estate of Rod Dresser

Left to right: Maggi Weston, Leonard Vernon, Marjorie Vernon, photo by Rod Dresser, © Estate of Rod Dresser

Oral histories strive to gather a wide range of information in the most neutral manner in order to capture in full a subject or an event. Our singular event was thirty-plus years of collecting. I was around for some of those years, so it was hard for me to remain neutral on the subject. Nevertheless, we conducted our interviews following oral-history protocol: a standardized set of questions, building from basic to more in depth. After the first few sessions, we noticed some interesting intersections and images that came up—along with far too many chances to go off script!

Our interview list was culled from a cross-section of artists, curators, gallerists, independent dealers, appraisers, conservators, and collections managers who knew the Vernons, at the time, in a singular dimension. Many of these individuals now play important roles in the realm of contemporary art in Los Angeles. Furthermore, the Vernons’ relationship with these individuals have long since evolved as time passed—by the time the oral-history project was mounted, these same people were citing the Vernons not merely as professional acquaintances, but as close friends. The line between objective history and the personal became blurred.

Contrary to what springs to mind with an oral history (audio quotes), we found ourselves amassing a list of images. These were photographs that consistently resonated with interviewees, some of whom were able to see them on display during repeat visits to the Vernon home, which functioned as a veritable salon for photography from the late 1970s until Leonard’s passing in 2008. Others sought out the Vernons, in many cases a Vernon visit was more integral to researchers than any local institution’s collection. Ryan and I waited with anticipation during each interview to find out which images might be added and which ones would grow another nuanced layer, building off the spiral of stories surrounding one image.

By the close of our project, it was clear that this fact-gathering exercise had grown to symbolize much more. This oral history will serve to make the family story as visible now as the photographs selected for display in See the Light. And from here on, I refer to the Vernon Collection as an acquisition of a family’s history with photography . . . and, oh yes, also 3,500 works.

Ryan Linkof, Ralph M. Parsons Curatorial Fellow in the Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography, shares his experience working with the Vernon Collection in part two of this series, which will be published next week.

Eve Schillo, curatorial assistant, Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography