Chinese New Year begins tomorrow, January 31, 2014. To celebrate, we will talk about several pieces from LACMA’s permanent collection of Chinese art that feature the auspicious horse, which is this year’s zodiac. For thousands of years, equines have been one of the most popular animals depicted in Chinese art, and the following examples only provide a glimpse into the rich historical and symbolic significance of horses.

In the early history, it appears that the horse was considered a close kin of dragons. Equipped with imaginary powers, horses would carry the soul to an imagined land after death. An Eastern Han dynasty horse, probably excavated from a tomb in the Sichuan province, displays such a celestial quality. Its left front leg is about to move forward, with the hoof barely touching the ground. Its tail flies upward, rendering the solid body a sense of elevation, as if the horse was dancing or flying. In fact, flying horses are often found in Han dynasty tombs, remarking on the belief its ability to carry the soul to the afterlife realm.

China, Sichuan Province, Eastern Han dynasty, Funerary Sculpture of a Horse, A.D. 25–220, gift of Diane and Harold Keith and Jeffrey Lowden

China, Sichuan Province, Eastern Han dynasty, Funerary Sculpture of a Horse, A.D. 25–220, gift of Diane and Harold Keith and Jeffrey Lowden

The animal was also a military necessity. The strength of a cavalry was important to defend kingdoms and empires from the threat from northern and Central Asian nomads. Essential to securing territorial integrity and maintaining sovereign independence, it is natural that horse was soon connected symbolically with power. By the Tang dynasty, the horse’s symbolism as an imperial power became even more pronounced.

China, Middle Tang dynasty, Funerary Sculpture of a Horse, about 700–800, gift of Nasli M. Heeramaneck

China, Middle Tang dynasty, Funerary Sculpture of a Horse, about 700–800, gift of Nasli M. Heeramaneck

China, Tang dynasty, , Funerary Sculpture of a Horse and Rider, 618–906, the Phil Berg Collection

China, Tang dynasty, , Funerary Sculpture of a Horse and Rider, 618–906, the Phil Berg Collection

In addition to the tribute horses brought to the Tang capital by the neighboring states, it is said the imperial court had a herd of over 700,000 horses. The sancai (three-colored glaze, brown, green, and cream) horse in the LACMA collection was found in a Tang dynasty tomb. It has a saddle on top of a coverlet. Its crupper and breastplate are decorated with tassels. So is the bridle piece, demonstrating the status of the tomb owner. Its tail is also carefully braided, showing its military or ceremonial function. Equestrian and polo became popular sports in the Tang dynasty, played by both men and women, displaying the wealth and status of the riders.

China, Chinese, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period, Square Dish (Die) with Figure on Horse, 1662–1722, gift of Miss Bella Mabury

China, Chinese, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period, Square Dish (Die) with Figure on Horse, 1662–1722, gift of Miss Bella Mabury

For the Chinese scholars educated in the Confucian classics, the characteristic of horses were equated with one’s virtue and ability, as recognized in the story of Bole, a man with extraordinary understanding of equines. Without Bole’s recognition of its talents, a horse will only pull a cart in the market. Similarly, a Confucian scholar’s refinement and virtue need to be discovered and employed by a benevolent and enlightened ruler.

By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the horse appeared less frequently as an independent art genre. Instead, it subsided to the role of mounters in the depiction of popular fictions and dramas, such as the lacquer square dish carefully inlayed with shell and gold leaf, where an official riding a horse is about to enter the city gate. A repeating form, however, is a monkey riding on the back of a horse, a visual rebus meaning “immediate advancement in officialdom,” an auspicious wish for scholars with ambitions.

China, late Qing dynasty, Buckle in the Form of a Monkey on a Horse, about 1800–1911, gift of Patricia G. Cohan

China, late Qing dynasty, Buckle in the Form of a Monkey on a Horse, about 1800–1911, gift of Patricia G. Cohan

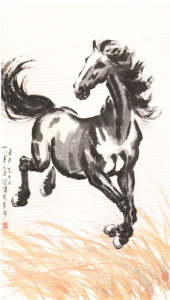

In the 20th century, the most celebrated horse painter is no doubt Xu Beihong. Trained in Shanghai, Tokyo, and Paris, Xu’s galloping horses combine the free and unrestrained expressions he was exposed in France and the traditional Chinese art of the brush and ink. The horses, always in vigorous sprinting gestures, embody a powerful political message: the noble and heroic spirit of China during the turbulent years of Sino-Japanese war.

Private collection, © Chen Art Gallery

Private collection, © Chen Art Gallery

In the popular culture of the Chinese zodiac system, each 12-year cycle is associated with a particular animal. For more than 2,000 years, people have believed that the attributes of each animal is reflected in those born in the corresponding year, affecting his or her personality and future. The horse is praised for its energy, strength, and intelligence, and cautioned against impatience and stubbornness.

Happy the Year of the Horse!

Christina Yu Yu, Assistant Curator, Chinese Art