One of the first things I noticed upon entering the exhibition See the Light—Photography, Perception, Cognition: The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection is the numerous quadrants of photographs arranged on the first wall. (Previously discussed in this Unframed post.) The four photographs in each grouping represent the four themes covered in the exhibition: descriptive naturalism, subjective naturalism, experimental modernism, and romantic modernism.

A number of photographs by William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the earliest adopters and promoters of photography, are included to illustrate the descriptive naturalism theme of See the Light. And understandably so—as a witness, and even a competitor, to the earliest methods of making photographs, Talbot was interested in the lens' ability to act as testimonial to what was situated in front of it. He trusted the lens to depict and describe reality better than the eye or through written observation.

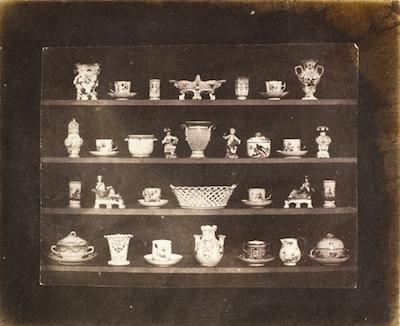

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China, c. 1844, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China, c. 1844, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

This photograph was made in 1844, a few years after the invention of commercial photography in 1839. Talbot used the method he invented—calotype—to construct this meticulously arranged field of china. Calotype, a process involving paper coated with silver iodide, was a departure from the daguerrotype, which required heavy plates and numerous contraptions to render an image. Talbot considered the ability to create images on paper a substitute to drawing as documentation. (It should be noted, however, that the calotype produced a less-detailed product than the daguerrotype.)

In The Pencil of Nature, published in London in the same year that the photograph (above) was made (Articles of China was also one of the plates of the book), Talbot writes that the illustrations in the book "have been obtained by the mere action of Light upon sensitive paper. They have been formed or depicted by optical and chemical means alone, and without the aid of any one acquainted with the art of drawing."

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China (detail), c. 1844, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China (detail), c. 1844, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Talbot continues, "The more strange and fantastic the forms of his old teapots, the more advantage in having their pictures given instead of their descriptions." I imagine he might have been referring to an object such as the one above.

It's remarkable to read Talbot's description of this image in the context of our visually saturated environment. To our 21st-century eye, Articles of China might perhaps be read as a simple grouping of porcelain objects. In essence, it is the consummate showcase for descriptive naturalism—it accurately represents the reality of that scene. To Talbot, however, someone who was exploring the nascent medium of photography, this picture presented an opportunity to capture all the intricate details present in each of the pieces of china.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China (detail), c. 1844, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

William Henry Fox Talbot, Articles of China (detail), c. 1844, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

We take this practical aspect of photography for granted, but it's incredible to consider that, just a mere decade before this picture was made, the only options to depict reality were either through painting, sculpture, or drawing. Talbot was right to examine and promote the possibilities of the medium. He writes, "The articles represented on this plate are numerous: but, however numerous the objects—however complicated the arrangement—the Camera depicts them all at once."

Although the mode of descriptive naturalism seems to have organically come about upon the invention of photography, its use is not unique to the 19th century. Straddling the boundaries between art and science, the crux of the descriptive naturalist strategy in photography—to serve as an objective eye—is still being used today. (The built-in camera on phones, for instance, often functions as a machine that produces testimony/proof of an event.) It's a rare opportunity to encounter the entire span of the history of photography in a singular exhibition, but when we do, we might realize that our passive consumption and production of images are linked to a trope that was the subject of fascination in the 1840s.

Linda Theung, editor