Remembering LACMA’s photography holdings before the acquisition of the Vernon Collection in 2008, former Photography Department head and curator Charlotte Cotton remarked, “when you went on to the museum database and searched for photographs from the 19th century, you could come up with, like, one picture . . . this was not a historical collection.” While LACMA did own more than one photograph from the era, Cotton was correct in essence. The acquisition of the Vernon Collection nearly tripled LACMA’s holdings in 19th-century photography, bringing works into the collection that would have been otherwise impossible to acquire (due to scarcity or price) by any other means.

Almost one-third of the works in the Vernon Collection (nearly 1,100 photographs) were produced before the outbreak of the First World War. From the first transaction to the last, the Vernons passionately collected the photography of the Victorian era. Maggi Weston, who sold the Vernons their first photographic works, remembered, “I wasn’t used to people in Los Angeles liking 19th-century work, but I took it with me to meet Leonard and Marjorie [Vernon] in L.A. . . . We got into this long discussion over the 19th-century work, and they ooh’d and awe’d. . . . They bought $10,000 worth of photographs on that first viewing.” This interest in the first several decades of photography’s history was given further strength by a trip to Oxford, England, in 1985, where the Vernons studied photography from the Victorian age with photographers and historians Anne Hammond and Mike Weaver, taking the opportunity while there to expand their growing collection of 19th-century work.

Benjamin Brecknell Turner, Whitby Abbey, Yorkshire, North Transept, c. 1854, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Benjamin Brecknell Turner, Whitby Abbey, Yorkshire, North Transept, c. 1854, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

The exhibition and accompanying catalog See the Light—although containing only a small, if exemplary, fraction of the works in the collection—offers a thorough education in the evolution of the medium across the 19th century. From the ghostly impressions of the earliest salted paper prints to the warm tones and bleached-out skies of mid-century albumens, and the moody platinum, bromoil, and gelatin silver prints from the turn-of-the-20th-century, the viewer has the unique opportunity to explore the range of photography’s possibilities in its formative decades. Even the most cursory perusal of the first few galleries of the exhibition, which are dominated by works from the 19th century, is enough to remind us how imprecise it is to use “black and white” to describe photography before the advent of color. A broad range of hues and colors etched themselves into Victorian era photographic papers. We quickly surmise that experimentation was important for early photographers—testing new methods, seeking new visual effects, and employing novel strategies for fixing, toning, and printing photographs. We are reminded that photography emerged and developed at the nexus of science, art and commerce—the dizzying diversity of materials and approaches testifies to that fact.

Gustave Le Gray, The Great Wave, Sète, 1857, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Gustave Le Gray, The Great Wave, Sète, 1857, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

The one figure who perhaps most exemplified the combination of science, art, and commerce in photography’s early history was William Henry Fox Talbot, who is represented by four works on display in the show. One of the leading figures in the “simultaneous invention” of photography in the 1830s, Talbot was the first to patent a positive/negative process (the salted paper Calotype). Although he is often associated with his scientific and technical achievements, he was also animated by an interest in art and aesthetics, and his images are some of the most haunting and engrossing in the history of photography.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Lace, 1841, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

William Henry Fox Talbot, Lace, 1841, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

It has often been pointed out that Talbot’s interest in photography emerged in part because he was a failed draughtsman—incapable of making effective drawings, he invented what he called “photogenic drawing,” the virtues of which he spelled out in his book with the equally telling title The Pencil of Nature, on display in the exhibition. Works such as A Fruit Piece borrow from the traditions of still-life painting to draw attention to the fleeting, even unsettling, ephemerality of objects in the physical world. His works used the veridical authority of the camera to draw attention to the oddness of things—the physical thing-ness of objects, for lack of a more elegant description. The eerie isolation of the objects in darkened space emphasizes the literalness of the camera’s transcription of reality, and reminds us that these real things in the world will decay and rot, while their photographic trace will remain. For these reasons, and certainly more, Talbot was a favorite of the Vernons, who owned nine works by him—a truly astounding number, given their rarity. The acquisition of the Vernon Collection represented a four-fold increase of the works by Talbot in LACMA’s collection, and for that, we are forever grateful.

William Henry Fox Talbot, A Fruit Piece, 1844–46, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

William Henry Fox Talbot, A Fruit Piece, 1844–46, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

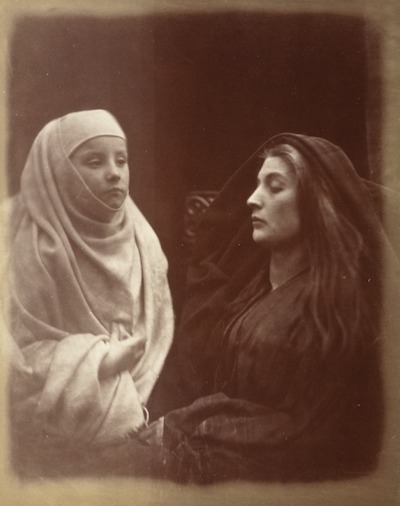

Another photographer working in 19th-century England who was of particular importance to the Vernons—and to the history of photography—is Julia Margaret Cameron. For her, photography was an expressive medium that could be harnessed in the service of fine art. Actively involved in the artistic and literary culture of her day, she made photographs in her glasshouse studio, often costuming her subjects to evoke Arthurian legend and Pre-Raphaelite painting and drawing. Using the then-current wet-collodion process, she never sought to make finely detailed and neatly developed images, and her works are characterized by their vital expressiveness and sense of emotion and immediacy. Unlike most studio portraits of the day, Cameron’s images, such as that of Mrs. Herbert Duckworth on display in the exhibition, lack the rigid frontality and formality characteristic of the form. Cameron influenced the impressionistic, dreamlike imagery that would become a central focus of photographers eager to assert photography’s artistic merits in the succeeding generation.

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Little Novice & Queen Guinevere In The Holy House Of Almsbury, 1874, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Little Novice & Queen Guinevere In The Holy House Of Almsbury, 1874, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs. Herbert Duckworth (née Julia Jackson), c. 1867, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs. Herbert Duckworth (née Julia Jackson), c. 1867, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

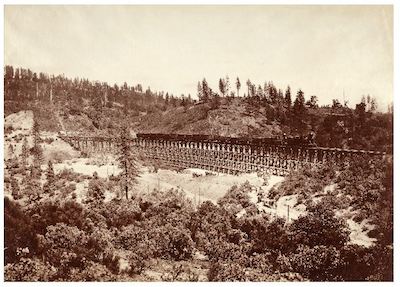

Whereas Cameron’s images impress with their emotional depth and sense of immediacy, many of her most notable contemporaries—such as fellow countrymen Francis Frith and Antonio Beato, as well as Carleton Watkins in the United States—sought to harness the power of photography to create monumental, timeless images, freezing the physical world and capturing it as accurately as possible for posterity (and for commercial gain). With the notable exception of the washed-out skies (a product of the sensitivity of the chemicals used in development to the blue end of the color spectrum), these images offer a detailed catalog of the built and natural environment, designed to bring exotic places into the homes of metropolitan consumers.

Francis Frith, Pyramids Of El-Geezeh (from the Southwest), c. 1857, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Francis Frith, Pyramids Of El-Geezeh (from the Southwest), c. 1857, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

When standing in front of these monumental images of far-flung destinations, we are reminded of the physical exertion that they must have required. Contact prints made from glass plates of substantial size, these images required an arsenal of equipment to capture and develop the image without the aid of running water or a climate-controlled development room. Watkins’s The Secret Town Trestle, Central Pacific Railroad, Placer County is the very apotheosis of mid-19th-century engineering—the feat of capturing the image nearly on par with the act of building the railways that knitted together a rapidly expanding country.

Carleton E. Watkins, The Secret Town Trestle, Central Pacific Railroad, Placer County, c. 1876, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Carleton E. Watkins, The Secret Town Trestle, Central Pacific Railroad, Placer County, c. 1876, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

One of the great masters of 19th-century American photography, Watkins was very sparsely represented in LACMA’s collection before the arrival of the Vernon Collection. The Vernons were partly responsible for the escalation in prices that placed Watkins prints out of the hands of many museums. Denise Bethel, now senior vice president and head of Department for Photographs at Sotheby’s, noted that the Vernons were willing to pay “a small fortune for one of the few Watkins mammoth-plate albums to come to auction. It is a story that has since made its way into the legends of the market, and I can tell you that it would have taken nerves of steel to go that high on any photographic property in 1979.” We are certainly glad to know (now that the collection has made its way to LACMA) that the Vernons had such nerve.

Frederick H. Evans, A Sea of Steps—Wells Cathedral, 1903, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Frederick H. Evans, courtesy Janet B. Stenner

Frederick H. Evans, A Sea of Steps—Wells Cathedral, 1903, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Frederick H. Evans, courtesy Janet B. Stenner

The last major purchase of Leonard’s life was also one for the record books, and represented the culmination of a decades-long love affair with the photography of the 19th century. Frederick Evans’s A Sea of Steps, Wells Cathedral, was referred to by many who knew the Vernons as his “Holy Grail”—the one work that he simply had to have. He acquired the work in 2007, not long before he passed. Although the Vernons had acquired an Evans portfolio several years prior, it was incomplete, with this image missing. When it came up for auction in New York, he was, by all accounts, ecstatic, and he insisted that he would not let the piece pass him by. Although he wasn’t in the best of health, he aggressively managed the transaction from bed, insuring that he was the highest bidder. Once it was acquired, he had the gallery in his home hung entirely with images of stairs, with this as the centerpiece. So while the image was not in the Vernon’s home for long, it was certainly a showpiece during the time that it was there.

A Sea of Steps, with its atmospheric tones rendered so vividly in this platinum print, is a powerful testament to the ability of photography to apprehend the world, and to imbue it with new meaning. The Vernon Collection has done something similar for LACMA’s photography holdings—allowing curators and visitors alike to bring their own interpretations to photography’s long, multilayered history.

Ryan Linkof, Ralph M. Parsons Fellow, Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography