Velvet, fur, satin, metalwork, hair, water, and stone. These are just some of the distinct surface textures that our eyes convince us we can “feel” as we look at mezzotints. Derived from the Italian mezza tinta (“halftone"), mezzotint is an intaglio process that developed in the 17th century in the Netherlands. It is the only printmaking technique that works from dark to light. A copper plate is uniformly inscribed with indentations made by the teeth of a metal rocker, allowing for ink to pool into these grooved areas. Without further manipulation, a solid dark, inky impression would result if one printed from the prepared plate at this stage. To generate the design for the image in the mezzotint, the artist or printmaker burnishes areas on the prepared plate to create the form of the image. These burnished sections enable varying degrees of ink saturation, resulting in a mixture of tones. If the indentations on the plate are completely smoothened and polished away, only the clean surface of the paper will appear in the image—no ink will print in these areas.

Jan Verkolje I, William III, King of England, c. 1688, gift of David and Francis Elterman through the Graphic Arts Council

Jan Verkolje I, William III, King of England, c. 1688, gift of David and Francis Elterman through the Graphic Arts Council

The pinnacle of popularity for the mezzotint took place in Britain during the 18th century. Allowing for a greater dissemination of images, mezzotints were prized by a discriminating clientele who wanted printed facsimiles derived from paintings. Valentine Green was one of the most prolific and famous of the mezzotint practitioners, and his designs were primarily modeled on portrait paintings by artists such as Joshua Reynolds and genre and scientific scenes, such as those painted by Joseph Wright of Derby.

Valentine Green, after Joshua Reynolds, Lady Elizabeth Compton, 1781, Mr. and Mrs. Allan C. Balch Collection

Valentine Green, after Joshua Reynolds, Lady Elizabeth Compton, 1781, Mr. and Mrs. Allan C. Balch Collection

The current installation includes two portraits by Green after paintings done by other artists, including the elegant portrait of Lady Elizabeth Compton, done after Reynolds. Elizabeth is posed informally in front of a bucolic English garden landscape and the viewer’s eye is drawn to her upswept coiffeur, her dress with its cascading folds of ivory-colored fabric, and her delicate satin shoes.

John Dixon, after Francis Swain Ward, Omdut il Mulk, Nabob of Arcot, 1771, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Pratapaditya Pal

John Dixon, after Francis Swain Ward, Omdut il Mulk, Nabob of Arcot, 1771, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Pratapaditya Pal

Another stunning portrait is John Dixon's oriental subject, Omdut il Mulk, the Nabob of Arcut, after a painting by Francis Swain Ward. The turbaned Nabob represents an exotic culture in his non-European costume accompanied by a caparison of weaponry and jewels. The large size of these prints also complements the convincing adaptation of the original paintings in printed form, as they display how the mezzotint technique can adroitly reproduce the details of the original artworks.

The ability of mezzotint to imbue a romantic quality of shadow and light is seen to great effect in prints that highlight landscapes and seascapes, derived from both literary sources and from natural settings.

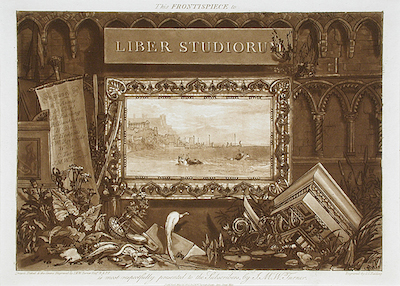

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Frontispiece to the series Liber Studiorum, 1812, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Martin Medak

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Frontispiece to the series Liber Studiorum, 1812, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Martin Medak

Joseph Mallord William Turner's Liber Studiorum series features the artist’s approach to designing the drawings for each of his subjects which were subsequently given to professional printmakers to copy in etching and mezzotint. The goal was to replicate an appearance of drawing within the printed medium, hence the use of brown-toned inks instead of black to more closely reproduce the sepia tones of Turner's actual drawings.

Frank Short, The Night Picket Boat at Hammersmith, c. 1916,

Frank Short, The Night Picket Boat at Hammersmith, c. 1916,Mr. and Mrs. Allan C. Balch Collection

Finally, Frank Short's atmospheric view of London and the Thames River in the early twentieth century has an almost German Romantic aura in its employment of mezzotint to soften and dissipate forms and to suggest distinct sources of light emanating from the boats and upon the water in this nocturnal moonlit river scene.

See these works in the installation on view on the third floor of the Ahmanson Building, across from the elevators.

Claudine Dixon, Curatorial Administrator, Prints and Drawings Department