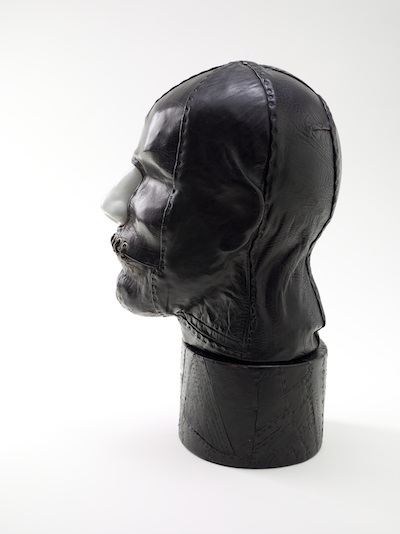

In 1968—a turbulent year of political upheaval, assassinations, demonstrations, and war—Nancy Grossman emerged as the creator of mysterious leather-bound heads, such as No Name, that became icons of modern art. Each of these heads was meticulously crafted, taking months to carve in found wood, then to encapsulate in a skin of black leather that was designed, cut, sewn, and tacked together by Grossman herself. Although they seemed to have emerged from the postwar assemblage movement that was lauded as an historical phenomenon in 1961 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, these heads initially posed more questions then they answered. No Name is an anonymous person whose bondage has restricted his seeing and speaking, his mouth cruelly stitched shut by a shoelace and wire. Was it male or female, did the color of the leather signify a flesh tone? Was it intended to signify the censorship of protestors? To all these questions, the artist remained silent.

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

The black-leather heads were innovative, and yet existed within strong artistic traditions. Black-paper silhouettes appeared in the eighteenth century to record people’s characteristic profiles. Ironically, silhouette figures reappeared in the 1960s in paintings by several Pop artists to signify anonymity. In their monstrosity and enigma, Grossman’s heads suggest strong ties to Surrealism. A cross between sculpture and assemblage, they hark back to the surrealist fascination with three-dimensional objects, especially of anatomical parts. In the 1930s French Marcel Jean and English Eileen Agar created cloth-covered heads with an assortment of materials not usually used in sculpture. Surrealists often masked or used other cloaking devices to hide physiognomy in order to heighten the ambiguity of their art.

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

The female Surrealists offered a strong foundation for artists during the feminist movement of the late 1960s and 1970s. Grossman was one of many women, including Dorothea Tanning and Eva Hesse, who explored new materials for sculpture, thereby undermining what had previously been deemed traditional. Over the years she continued the series of heads, adding harnesses, zippers, and chains to intensify the element of bondage and sexuality, then horns to question the anthropomorphic nature of her creatures, and eventually unwrapping the eyes and mouths so her creatures directly confronted the viewer. It was difficult to believe that Grossman, a small, attractive young woman with a bountiful head of curly black hair, could and would create such physically powerful images. Determined to transform personal identities, social relations, and power structures, the Women’s Movement encouraged feminist artists to challenge the standard ideas of what constituted “feminine art.” And that is exactly what Grossman did.

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

No Name was acquired during the 29th-annual Collectors Committee through the generosity of Stewart and Lynda Resnick, whose continued commitment to LACMA has resulted in enormous growth to both our campus and the collection. The sculpture soon will be on view in the American Art galleries.

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Nancy Grossman, No Name, 1968, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2014 Collectors Committee, © Nancy Grossman, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Ilene Susan Fort, Senior Curator and Gail and John Liebes Curator, American Art