In one painting, a dragon’s powerful body writhes in space as it hurtles through clouds and mist. In another, a Zen master leans on his pet tiger; both the monk and the tiger are sound asleep. In a third, two Zen eccentrics sit on the exposed roots of a pine tree and cackle with laughter in a mountain forest. Dating to the 13th and 14th centuries, these three paintings are among the many masterpieces included in the first installation (May 11–June 1) of Chinese Paintings from Japanese Collections, which opened yesterday to the public in LACMA’s Resnick Pavilion. Included here are Buddhist, Daoist, and secular themes, beautiful nature studies in both monochrome ink on paper and heavy mineral colors on silk, and towering mountain landscapes.

Traditionally attributed to Shike (active 10th century), Two Patriarchs Harmonizing their Minds, China, Southern Song dynasty, 13th century, Tokyo National Museum, Important Cultural Property

Traditionally attributed to Shike (active 10th century), Two Patriarchs Harmonizing their Minds, China, Southern Song dynasty, 13th century, Tokyo National Museum, Important Cultural Property

I first dreamed of organizing this exhibition in the late ’80s and am thrilled to have been given the opportunity to bring the project to realization at LACMA. The show includes some of the most famous Chinese paintings in the world, the majority of which have never before been seen in the United States. These works were acquired in China over many centuries, both through gift and purchase, and functioned in Japan as symbols of Chinese culture, markers of social status, and models for major traditions of Japanese painting. The exhibition explores Japanese taste in Chinese art, and the history of collecting Chinese paintings in Japan over 700 years, from the 13th through mid-20th century.

Attributed to Wang Wei (699–759), Fu Sheng Transmitting the Classic, China, Tang dynasty, 8th century, Important Cultural Property, Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Attributed to Wang Wei (699–759), Fu Sheng Transmitting the Classic, China, Tang dynasty, 8th century, Important Cultural Property, Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

The earliest painting in the show is, amazingly, over 1,200 years old. It dates to the eighth century, and is attributed to Wang Wei, a famous poet and painter of the Tang dynasty. Painted on silk, the scroll depicts the old scholar Fu Sheng, who single-handedly rescued a copy of the ancient Book of Documents (Shu Jing) from an infamous book burning in 213 B.C., ordered by the draconian first emperor of the Qin dynasty (Qin Shihuangdi)—around whose tomb the famous life-size terra cotta army was discovered in the 1970s and ’80s. The painting celebrates scholarship and knowledge of the past, for the Book of Documents contains the protocol for the transmission of Heaven’s Mandate from a fallen dynasty to its successor—a protocol that was used by every subsequent dynasty in Chinese history to establish its political legitimacy.

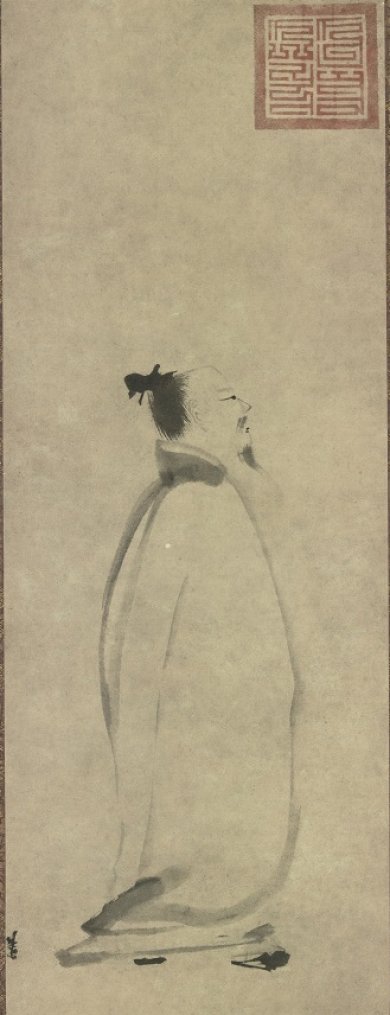

Liang Kai, The Poet Li Bai Chanting a Poem on a Stroll, Southern Song dynasty, Important Cultural Property, Tokyo National Museum

Liang Kai, The Poet Li Bai Chanting a Poem on a Stroll, Southern Song dynasty, Important Cultural Property, Tokyo National Museum

Perhaps the most famous scroll in the exhibition is the 13th century painter Liang Kai’s portrait of Li Bai, one of China’s most celebrated poets who lived in the eighth century. This beautiful scroll, painted with great economy in ink on paper, depicts the poet strolling and chanting a poem. The painting had an enormous impact in Japan, especially on ink painters of the Muromachi (1333–1568) and Edo (1600–1868) periods. The care with which such paintings were kept in Japan is illustrated by the scroll’s multiple wooden boxes and cloth wrapping, which are also on display in the exhibition. These beautifully crafted boxes also hold numerous authentication documents, the earliest of which dates to 1707.

Traditionally attributed to Ren Renfa, Four Elegant Pastimes, Early Ming dynasty, 14th–15th century, Tokyo National Museum

Traditionally attributed to Ren Renfa, Four Elegant Pastimes, Early Ming dynasty, 14th–15th century, Tokyo National Museum

In addition to such world-famous works, the exhibition also includes several superb paintings that are lesser known and have also never before been seen in the United States. In traditional China many paintings by professional (as opposed to literati or amateur) artists were created in sets of four hanging scrolls. These were often arranged by the seasons, with sets illustrating the sequence of spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Such sets have rarely survived in China, but many more have survived in Japan. One of the oldest surviving sets of this type comprises the theme of The Four Elegant Pastimes, which were four separate arts: playing the zither known as the qin (pronounced “chin”), playing the board game of weiqi (known in Japan as go), calligraphy, and painting. The beautiful set depicting the Four Elegant Pastimes in the exhibition bears the signature of the 14th-century painter Ren Renfa, but is more likely an anonymous work of the early Ming dynasty (15th century) to which spurious signatures were later added. That these paintings were admired and closely studied in Japan is clear from the existence in the Tokyo National Museum of four Japanese Kanō School copies, which are published for the first time in the exhibition catalogue.

Installation view, Chinese Paintings from Japanese Collections, May 11–July 6, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation view, Chinese Paintings from Japanese Collections, May 11–July 6, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Another work shown for the first time in the United States is a 16th-century handscroll depicting 10 famous Daoist pilgrimage sites. A joint work created by three painters and eight calligraphers for a Daoist named Shen Oujiang, this handscroll includes scenes of famous caves known in Daoism as “cavern-heavens” (dongtian)—primordial spaces that were believed to exist outside of time—and “auspicious lands” (fudi). These had been listed and categorized in the late Tang dynasty (ninth century) and were situated in mountains that were considered sacred to Daoism.

Due to the fragility of the works, the exhibition will undergo a rotation in the first week of June (June 2–6). The second part of the exhibition opens to the public on Monday, June 7, and will feature one of my favorite paintings from the 14th century. Stayed tuned for more on that in a future Unframed piece.

Because of the rarity of its contents, Chinese Paintings from Japanese Collections will only have one venue in the United States: LACMA. The exhibition includes a National Treasure and 13 Important Cultural Properties, all designated by the Japanese Ministry of Culture as works deserving special care, and the display of which is strictly limited. For viewers in the United States, this exhibition presents a rare opportunity to see some of the most famous Chinese paintings in Japanese collections, and to explore the ways in which one culture (Japan) has appropriated works of another culture (China) and made them vital components of Japanese culture. As such these works are mirrors of both cultures, and speak to the rich cultural dialogue between the two nations over a period of many centuries.

Stephen Little, Curator and Head of the Chinese and Korean Art Department