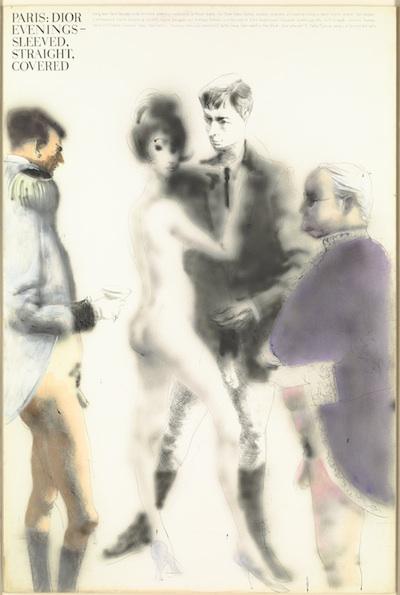

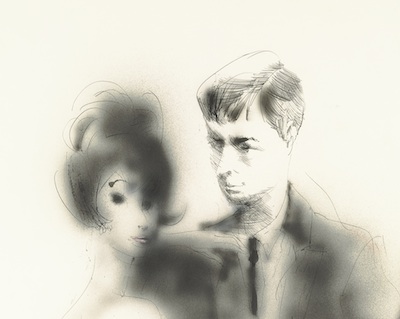

“OMG, it looks so 1960s!” That has been the response of any number of people when they first see John Altoon’s Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings), c. 1962–63, currently on view in a retrospective of the artist’s work at LACMA. I think that reaction is based on the bouffant hairdo worn by the sole woman in the image, a coiffure that is so reminiscent of Jackie Kennedy and 60s haute chic. Even the woman's right eyebrow is arched uncannily like Jackie's. And of course the square-jawed man whose tie she is straightening is similarly cut out of the John F. Kennedy mold.

John Altoon, Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings), c. 1962–63, private collection, courtesy Fred Hoffman Fine Art

John Altoon, Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings), c. 1962–63, private collection, courtesy Fred Hoffman Fine Art

John Altoon, Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings) (detail), c. 1962–63, private collection, courtesy Fred Hoffman Fine Art

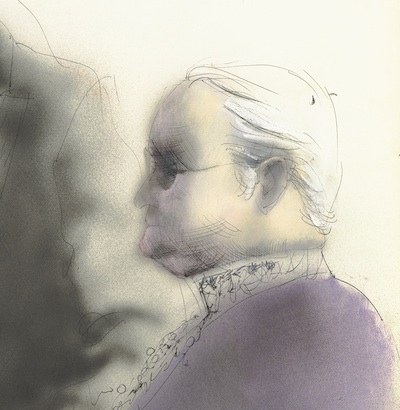

John Altoon, Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings) (detail), c. 1962–63, private collection, courtesy Fred Hoffman Fine Art

It is revealing to look at this image in the context of the early 1960s, a moment just before the explosion of the women’s movement. This was the decade in which Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique in 1963, the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 prohibited discrimination based on gender (among other things), and the National Organization for Women (NOW) was founded in 1966. The Los Angeles art scene in the 1960s was dominated by artists and gallery owners who were mostly men. The renowned Ferus Gallery, where Altoon’s work was seen in 15 shows (including five solo exhibitions) from the gallery’s opening in March 1957 through June 1963, was known to have a male-centric roster.

Altoon himself is often considered one of the “Ferus Gallery Studs,” a term borrowed from the title of an exhibition at the Ferus Gallery that featured an all-male group of artists (the sexist overtones of that moniker are not coincidental). Billy Al Bengston, an artist who was featured in the four-man show and who coined its title, later explained, “Two-by-fours are called studs, and there were four us in the studs show. We were holding the gallery together as far as I could see, so we were the studs. I have nothing against creating a little bit of drama if there’s nothing going on.” Despite all this evidence that points to Altoon’s alleged chauvinism, Untitled, like a good many of the artist’s other works, is hardly a statement about male dominance.

The drawing, which stylistically reflects Altoon’s training as a commercial artist (he was also trained as a fine artist), is a hallucinatory vision of a Dior fashion show, depicting three well-, if half-dressed men: one wears epaulets, one a suit jacket and tie, and one (who may be Christian Dior himself with his thick neck, distinctive nose, and receding hairline) a beaded cutaway.

John Altoon, Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings) (detail), c. 1962–63, private collection, courtesy Fred Hoffman Fine Art

John Altoon, Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings) (detail), c. 1962–63, private collection, courtesy Fred Hoffman Fine Art

There is also the one woman in the drawing, completely naked save for high heels, hardly the typical haute couture runway model. The relationships between all these figures are unclear. Is the central male accosting the woman, whose eyebrows may be arched in surprise, or is she the vixen and he the victim? The inscription on the drawing, “Paris: Dior Evenings—Sleeved, Straight, Covered,” can be read as a pun on various levels, for none of the figures is fully covered, and “sleeved” and “straight” can both be understood to have sexual connotations. The men are not wearing “sleeves” (condoms), and Dior was known to be gay (not “straight”).

The longer inscription across the top of the drawing refers to the “deliciously spooked-up ambiance of the Musée Grévin,” a waxwork museum in Paris with scenes depicting both French history and contemporary life. Like the figures seen in wax museums, those presented in Altoon’s drawing create a disjunctive jumble of characters who, based on their (demi) attire, belong to varied worlds. Although any given figure in the Musée Grévin is readily identifiable, the connections among those wax personae—who range from 18th-century French royalty to Hollywood celebrities—are usually nonexistent, as with the figures in Altoon’s drawing. Untitled (Paris: Dior Evenings) thus seems both essentially of the early 1960s and strangely outside of time.

Carol S. Eliel, Curator of Modern Art