It is hard not to be seduced by the 36 enigmatic photographs that make up John Divola’s Artificial Nature, currently on view as part of the exhibition John Divola: As Far as I Could Get, which closes this Sunday. Made by anonymous photographers working on the sets of films produced during the classical era of Hollywood movie making (roughly 1930–60), the photographs were generated by the millions—yet another industrial element of the so-called dream factory. Produced from 8 x 10 glass negatives, the direct contact prints feature a remarkable amount of detail and image clarity. Eerie and lifeless and packed with incidental information, they are arresting objects in their own right, worthy of close scrutiny.

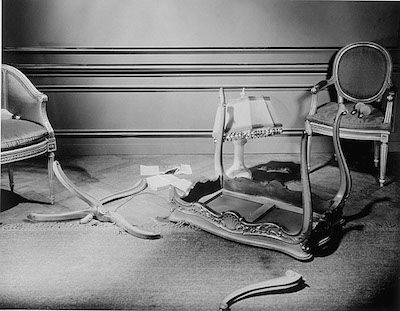

Artificial Nature, first exhibited in 2002, is the most recent addition to Divola’s Continuity series, in which he appropriated set stills to create his own conceptual artworks. Beginning in the 1990s, he began to exhibit these production photographs mined from the vaults of the major Hollywood film studios. In a series of displays, he grouped them by theme, or genre type: hallways, stairs, mirrors, and “evidence of aggression”—the latter of which recorded the traces of violent activity in domestic settings, much like his own well-known photographs of vandalized abandoned homes.

The original purpose of the set still was simple and utilitarian: to aid in the construction of seamless cinematic narratives, ensuring that the sets remained constant from take to take. A genre built around the static image—the very name connotes stillness—the set still seems to betray the logic of cinema. Such frozen images are anathema to the visual effect of “motion pictures.” It is this paradox, among others, that Divola interrogates in his Continuity works.

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

Artificial Nature is a collection of images documenting the fabricated landscapes contained within the artificial space of the film studio. Representing diverse natural topographies and weather patterns, many of the images also include a small clapperboard with the title of the film or the name of the scene scrawled on it. If the viewer is seduced by the illusion of the cinematic vista, this small detail, interjected into an otherwise convincing representation, insists on the artificiality of the scene.

Fascinated by the haunting quality of these images, and wanting to dig deeper, I borrowed a page from Edward Dimendberg, the author of an essay in the 1997 book about Divola’s Continuity series: I planned to hunt down the films for which these stills were originally produced. True to the archival spirit of Divola’s project, I decided I would watch whichever films I could find. It turns out that this was trickier than I had originally thought. Only three films are identified by name. This fact alone speaks to the ways in which the images—entirely removed from their original context—can assume a variety of different meanings, shaped only by what is depicted and what information is provided on the clapperboard, which is blunt and deliberately generic, e.g., “Mountain Stream,” “Woods.”

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

Of the three films identified in the images—As the Earth Turns (1934), Ice Palace (1960), and The Mudlark (1950)—Ice Palace is the only one appearing multiple times. So, with that numerical advantage noted, I managed to find a VHS version of the film (no small feat) and gave myself the assignment of watching it in order to identify some of the sets that feature in the continuity images selected by Divola.

The film is a schlocky melodrama with Richard Burton and Robert Ryan about romance and valor in Alaska in the years before its statehood. The plot is irrelevant here, beyond the fact that it explicitly engages with ideas about the conflict between nature and civilization, which are at the core of Divola’s reappropriation of the set stills.

I watched the film closely and endured what I could of the narrative in my attempt to find the sets that appear in the set stills. This was much harder that one might think; I might even be forced to admit failure. At times, I wondered if I was even watching the correct film.

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

The most startling discrepancy between the static images in Artificial Nature and moving images in Ice Palace is that the film was shot in Technicolor, with the bold, saturated hues of late 50s/early 60s Hollywood. It was hard not be distracted by the clash of the abstract, monochrome qualities of the gelatin silver set stills, which flatten much of the visual texture and period character of the sets, and the hyperrealistic effects of Technicolor. I kept wondering, which is the less convincing approximation of the physical world? The deadened set pieces shown in Artificial Nature or the garish tones of the film itself? Perhaps a New York Times review of the film from the time said it best, “It is as false and synthetic a screen saga as has rolled out of a color camera in years . . . no more authentic than cornstarch snow on a studio set.” That reviewer found the studio sets “particularly phony-looking,” and bemoaned that a film explicitly concerned with wild nature was “shot entirely in a studio.”

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

John Divola, Artificial Nature (detail), 2002, 36 found gelatin silver prints from c. 1930–60; 8 × 10 each, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund and the Photographic Arts Council, 2013

Divola might agree with that review. At its core, Artificial Nature questions the way that the physical world is increasingly experienced as a representation—something that we understand through layers of mediation. In selecting these objects for display, he highlights how we have inserted a deliberate distance between ourselves and the natural world, a distance that is only accentuated by cinematic representation. In this work, as in so many others by the artist, we are brought back to the status of the photographic image as both truth teller and talisman—simultaneously a document and a cipher. My flaccid attempt at deciphering the continuity stills served only to remind me of their opacity and unreliability as referents to actual things in the world. Divola, I’m certain, would have it no other way.

Ryan Linkof, Assistant Curator, Wallis Annenberg Photography Department