It might not be immediately obvious, but two exhibitions currently on view at LACMA—one featuring Chinese paintings dating back to the seventh century and the other Expressionist works from the early 20th—share a number of themes. I sat down with curators Timothy Benson (Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies) and Stephen Little (Chinese and Korean Art) for a conversation about the ways in which these seemingly disparate exhibitions might share a story.

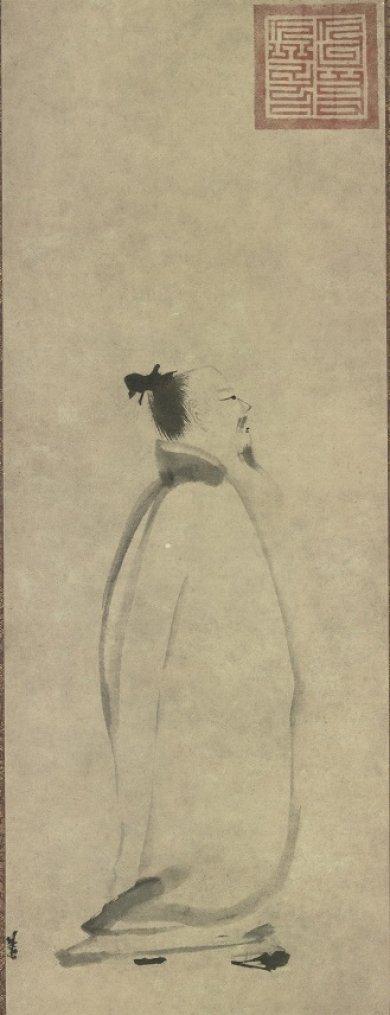

Liang Kai, China, The Poet Li Bai Chanting a Poem on a Stroll, Southern Song dynasty, 13th century, Hanging scroll; ink on paper, Tokyo National Museum, Important Cultural Property, image courtesy of TNM Image Archive

Liang Kai, China, The Poet Li Bai Chanting a Poem on a Stroll, Southern Song dynasty, 13th century, Hanging scroll; ink on paper, Tokyo National Museum, Important Cultural Property, image courtesy of TNM Image Archive

Paul Gauguin, Swineherd (detail), 1888, gift of Lucille Ellis

Paul Gauguin, Swineherd (detail), 1888, gift of Lucille EllisSimon and family in honor of the museum's 25th anniversary

The fundamental relationship between the two exhibitions can be found, surprisingly, in the objects. The paintings featured in both presentations tell stories about the patterns of collecting and the connoisseurs who sought these artworks. In organizing their respective exhibitions, the two curators aimed to examine the role of the collector—a figure perhaps of equal importance as the artist with regard to determining taste—in aesthetic judgment.

Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky is based on the premise of “what one might call cultural transfer,” says Benson. In other words, the exchange of ideas between cultures. Both Benson and Little looked at the role of collectors, dealers, and museum curators, all major players in the transfer of art objects. In the 19th century, for instance, there was popular interest in “non-Western” objects, an influence that can be traced in Van Gogh’s work in the 1880s. Beyond Van Gogh, many German artists featured in Van Gogh to Kandinsky also looked to the East to learn more about Chinese philosophy and Buddhist practices, motifs of which can be observed in Chinese Paintings.

Attributed to Wang Wei (699–759), Fu Sheng Transmitting the Classic, China, Tang dynasty, 8th century, Important Cultural Property, Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Attributed to Wang Wei (699–759), Fu Sheng Transmitting the Classic, China, Tang dynasty, 8th century, Important Cultural Property, Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

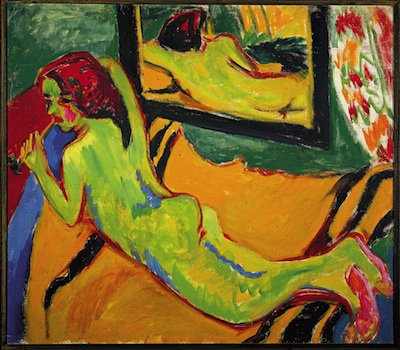

Perhaps the strongest similarity between the two presentations is showcased in how cultures are dependent on one another. Van Gogh to Kandinsky traces the relationship between French and German artists—one that is sometimes fraught with tension. German artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had what Benson termed as an essentialist identity. They saw themselves as a Nordic people interested in interiority in art practice. This differed with how they viewed artists in the south, such as France and the Mediterranean, who expressed verisimilitude and exteriority. Despite this contrast, German artists of the Brücke and the Blaue Reiter nevertheless absorbed French artistic aesthetics, appropriating it for their own practices.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Reclining Nude in Front of Mirror, 1909–10, courtesy Ingeborg & Dr. Wolfgang Henze-Ketterer, Wichtrach/Bern Photo © Brücke-Museum, Berlin

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Reclining Nude in Front of Mirror, 1909–10, courtesy Ingeborg & Dr. Wolfgang Henze-Ketterer, Wichtrach/Bern Photo © Brücke-Museum, Berlin

The relationship between Japan and China, on the other hand, was based not on a contrasting view of each other, but deep respect. Little outlines the main differences between Chinese and Japanese painting styles: virtuosity in Chinese painting was judged on the execution of deliberate and clear line and symmetry, whereas Japanese aesthetics prized mystery and elusiveness. Elements of Chinese painting were nonetheless important for centuries to Japanese artists.

The two exhibitions point out the cultural dependence of Japan and Germany’s artistic production on Chinese and French art, respectively. Both exhibitions trace the nature of intercultural relationships and their profound effects on works of art produced.

Moving beyond the works of art themselves, there’s also a link to tradition in the way the exhibitions were designed and installed. The designers of Chinese Paintings worked with Little on their inventive installation. The fruits of the collaboration resulted in something that has a high-tech look, an appearance that seems anathema to the delicate scrolls mounted on silk on view in the exhibition. Coincidentally, however, the installation hinted at the tradition of how the scrolls were originally displayed, in tokonoma, or recessed spaces.

Installation view, Chinese Paintings from Japanese Collections, May 11–July 6, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation view, Chinese Paintings from Japanese Collections, May 11–July 6, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Van Gogh to Kandinsky, designed by guest architects Frederick Fisher and Partners, borrowed its dark walls from the spaces in which the paintings were originally hung. The notion of the sterile, white gallery/museum box was an invention of the 1960s—before that, sumptuous colors aided (or even influenced) the viewing experience. The blue bands that serve as the backdrop to a number of paintings do more than just provide a contrasting color to the deep dark found throughout the exhibition: the hue also marks the fact that a particular painting was also on view in Paris.

Installation view, Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky, June 8–September 14, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation view, Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky, June 8–September 14, 2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA

While on view on opposite ends of the Resnick Pavilion, Chinese Paintings from Japanese Collections and Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky do share distant relations. The exchange between cultures, the role of the collector, and even the conversation between Asia and Europe, can be traced in these presentations.

Isabel Frampton Wade, Communications Intern

Linda Theung, Editor, Communications