Primeval forests, nocturnal flights of fancy, and a fire-breathing dragon are a few of the themes featured in the "Myths and Legends" section of Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s. Harkening back to earlier times from German art history, legend, lore, and literature, the two films that are highlighted in this section are Fritz Lang's The Nibelungen: The Death of Siegfried (1924) and F. W. Murnau’s Faust (1926). To complement the mysterious and dramatic atmosphere that is illustrated in the works on view, the exhibition installation design by Amy Murphy and Michael Maltzan of Michael Maltzan Architecture, Inc., pays homage to the subject matter with column-like structures to display the artwork, evoking a forest of trees within the museum galleries.

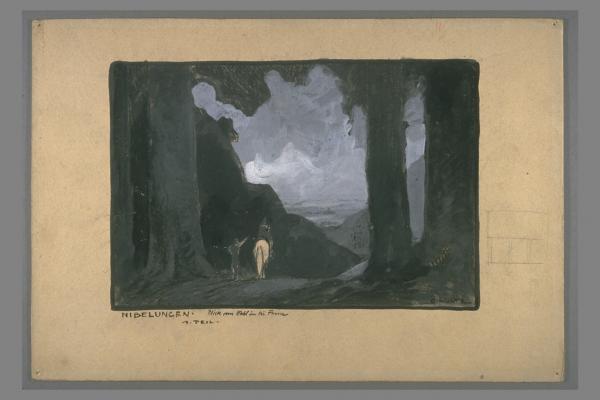

The story of Siegfried, the hero of Teutonic myth, is depicted in a group of drawings, done primarily in gouache and ink wash, by artist Otto Hunte, as well as in black-and-white photo stills from the film. Hunte was one of the set-design artists who worked for film director Fritz Lang, and his drawings display the initial ideas that led Lang to form the iconic compositions for specific scenes in his film. Lang is perhaps best known for his later German films, Metropolis and M—also featured in the exhibition—as well as for the American film noir features he made in Hollywood in the 1940s and 1950s. It was the early German films, however, such as the two-part Nibelungen, which introduce us to Lang's successful working method in collaborating with artists to bring epic stories to life.

Here we see the spindly birch trees that surround the doomed hero as he kneels to quench his thirst at the forest stream. With his backside facing his unseen assailant, Siegfried is unaware of the terrible fate that awaits him. Despite the moment of extreme violence suggested in the story, Hunte has instead placed emphasis upon the organic forms of the slender, wraith-like trees within the landscape rather than upon the foreground figures of Siegfried and his assassin. Our eyes are first drawn to the towering trees and the dappled play of light upon their trunks, rendered in variants of white and gray gouache on the sheet.

In all of Hunte's drawings for The Nibelungen, the landscape is predominant, similar to the painting style of the great 19th-century German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich. The drawings convey nature as all powerful (and often threatening), and the human and otherworldly figures within the environment are subservient to the omnipotent force of the natural world.

In addition to the many drawings on view, The Nibelungen is supported by a number of silver gelatin print film stills that capture the rich contrasts in the black-and-white film. All the drawings and photographs are from the collection of La Cinémathèque française in Paris, a bequest to that institution by German cinema historian Lotte Eisner. Also included in the exhibition is a jewellike book focusing on the Nibelungen saga from LACMA's Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies , with brilliant color and gold-leafed lithographic plates created by the Austrian artist Carl Otto Czeschka.

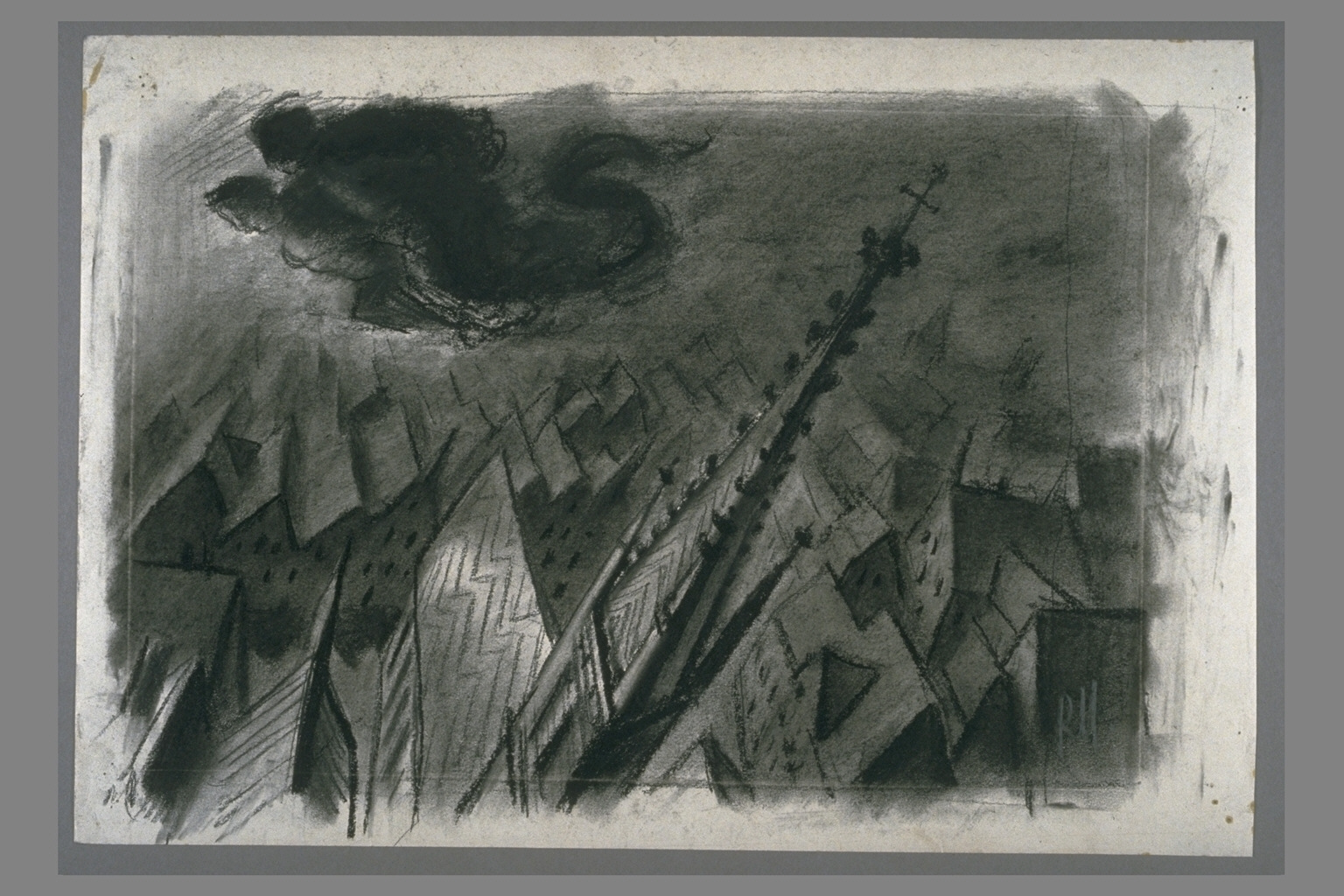

F. W. Murnau envisioned the tragic legend of Faust through the drawings done by Robert Herlth and Walter Röhrig, two artists who collaborated with him on the realization of his film. Although they formed a working partnership, Herlth and Röhrig were also competing against each other to produce the final drawings that Murnau would ultimately select for translating the specific scenes within his film. In this drawing by Herlth, Faust is accompanied by Mephisto on a journey above the earth, the billowing folds of the figures' cloaks producing the illusion of a giant bird soaring across the sky. The image conjures the illustrations found in children’s fairy tale books, such as for the tales written by the great German fabulists Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm.

Röhrig's more introspective composition depicts Faust as he contemplates his predicament upon a barren landscape that is visible from an aerial view that cuts off the horizon line at a skewed angle, reminiscent of the more "expressionist" lines and minimal forms that were evident in earlier films such as Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). This abstract formatting adds to the drawing's purpose as a document for the visual arrangement of the scene—it also succeeds in conveying the Stimmung, or the mood and atmosphere—that pervades the psyche of the alienated protagonist.

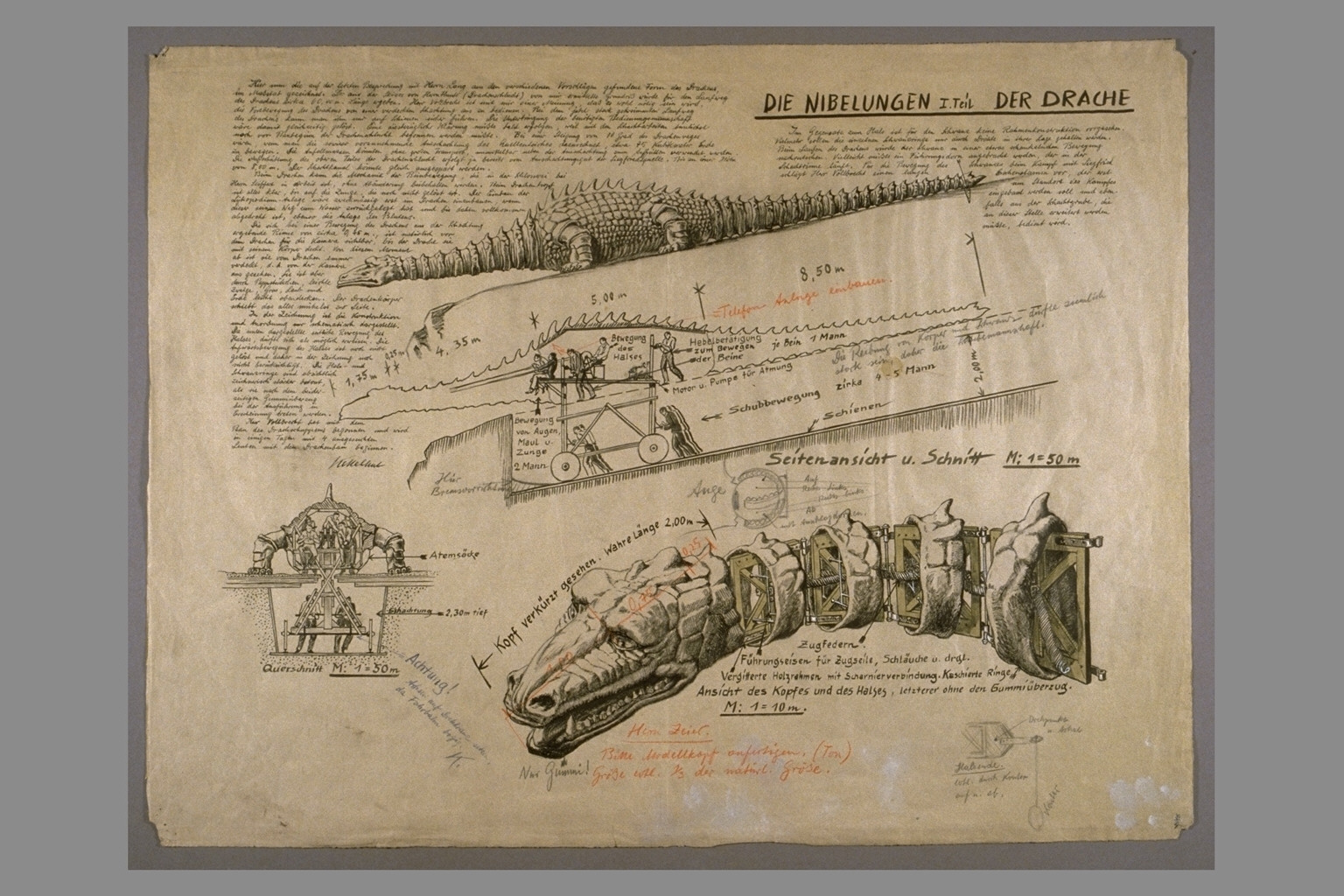

A spectacular working drawing for the model of the dragon in The Nibelungen is one of the masterworks in the exhibition. It was created by set-design artist Erich Kettelhut and includes detailed handwritten notations that describe how the dragon was manipulated in order to make it appear "alive." Each component of the dragon's constructed form is carefully delineated, showing the working mechanisms that were installed by the production designers. There is also a cross-section view of the dragon’s upper body. Especially intriguing is the red-penciled description, which indicates where a telephone connection should be installed inside of the dragon’s body for the person operating the interior machinery to communicate with the film crew outside—a hint of practicality within the fantasy that is being formed! This drawing may constitute one of the earliest studies related to cinematic special effects—showing the ingenuity of early filmmakers and their collaborators in the 1920s, realized without any of the computer technology that is taken for granted in the making of films today.