Visitors to the fourth floor of the Ahmanson Building will find a bright surprise waiting for them. For the first time since 1993, the Islamic art galleries have undergone a renovation that saw the removal of outdated cases and a low vaulted ceiling, the construction of new rooms, and the addition of benches and fresh carpet and paint. The changes in the galleries, however, are much more than just a facelift. Visitors will also find a selection of never-before-exhibited artworks on view in Islamic Art Now: Contemporary Art of the Middle East (part one is on view through January 3, 2016; part two opens on January 24, 2016).

The exhibition, which focuses exclusively on contemporary art of the Middle East, is a first for LACMA. Since 2006 curator of Islamic Art and department head Linda Komaroff has actively collected such art and, through the generous support of donors and the Art of the Middle East: CONTEMPORARY Council, the collection has rapidly grown to include nearly 200 artworks by artists from throughout the Middle East and its diaspora communities, becoming the largest collection of its kind in the United States. Over the years, works from this collection were exhibited alongside the historical Islamic art collection where space would allow.

Luckily for me, in 2008, a portion of the galleries was dedicated to exhibiting Shadi Ghadirian’s Untitled (Qajar) series. I instantly fell in love with Ghadirian’s photographs, which ultimately set me on the path to pursue a curatorial career in contemporary art of the Middle East. Five years later I joined LACMA’s staff and was thrilled to be a part of the planning and installation of Islamic Art Now.

The opportunity to realize a larger scale exhibition of LACMA’s contemporary Middle Eastern art collection came in 2013 when the historical collection began a world tour. Conceived as a two-part exhibition, the first iteration consists of 27 works by 21 artists and addresses a range of themes, cultural contexts, and artistic approaches that highlight the diversity of the region and its diaspora communities and the art emerging from both. Despite (or perhaps because of) being an ever-present subject of American news, the Middle East remains one of the least understood areas of the world. While not a cure-all for the misunderstandings and misrepresentations that plague the region, contemporary art of the Middle East does provide a visual alternative to what is typically covered in the nightly news and morning paper. It also gives voice to individual artists’ perceptions of their cultural origins, local politics, and history. In this way art provides new angles and avenues for understanding a complex region that ultimately expands and enriches a viewer’s perspective.

To this end, Islamic Art Now was designed to be largely open ended and without themes in order to create space for the inclusion of a range of artistic voices, subjects, and media. A few examples (and some of my favorite artworks) highlight this diversity. Entering the exhibition, viewers are met by Nasser Al Salem’s God is Alive, He Shall Not Die (blue), a stunning work made of neon, a material most often associated with convenience stores and Las Vegas, but that is used here to convey the deeply spiritual concept of the infinite nature of God.

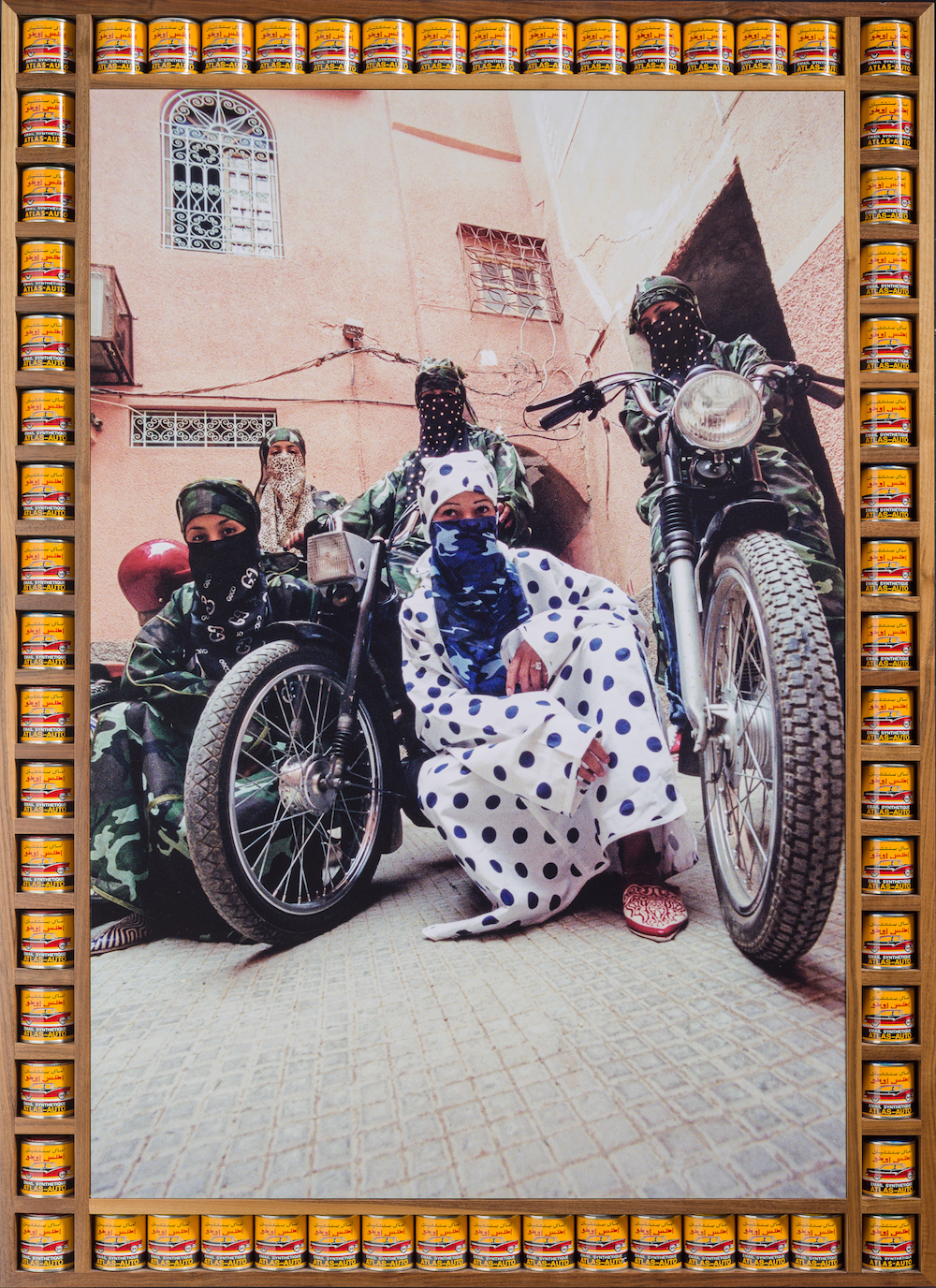

Moving further into the exhibition, viewers will find Gang of Kesh Part 2 by Hassan Hajjaj, which depicts a group of women clad in the traditional Moroccan djellaba, head scarf, and veil (playfully made in polka dots, camouflage, and leopard prints) posing as a biker gang, cheekily challenging stereotypical images of veiled women. Nearby, The House That My Father Built by Sadik Alfraji deals with the passing of the artist’s father and speaks to the universal concept of the evolving bonds between parent and child, generating an emotional charge that will resonate with any viewer.

Around the corner, Ahmad Aali’s Untitled (‘Down with Communism’), documents the turbulence of the Iranian Revolution, but rather than focus on the streaming crowds of protesters that have become so familiar through the news, Aali records in this photograph the revolution’s physical mark on Tehran through political graffiti, generating an almost serene composition that subtly alludes to the ensuing violence through dripping red paint.

It is my hope that these works and others in the exhibition will find as much resonance with visitors as they have for me. Perhaps another visitor will be inspired to similarly pursue a career in the field of art history. Most of all, I hope that every guest to Islamic Art Now will see the exhibition as both a challenge and an invitation to be curious and to further explore the history, cultures, and art of the Middle East.