Just over two months ago, Leslie Jones, Curator of Prints and Drawings, had decided upon the final placement of the works included in her exhibition, Drawing in L.A.: The 1960s and 70s. After the registrars and prep crew from Art Preparation and Installation (API) had finished the installation, I went into the galleries to review the final layout. I thought I would be alone that afternoon since the show wasn’t going to open to the public until the following week.

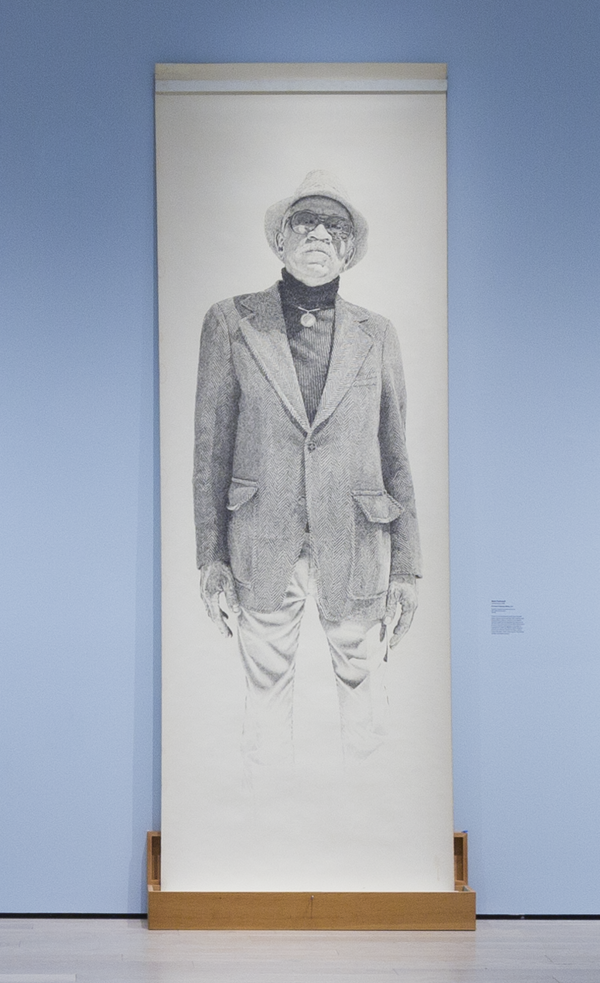

Entering the second gallery room, I was surprised to see one of my LACMA colleagues, Senior Art Preparator Cedric Adams, quietly sitting on the bench that is placed directly in front of the monumental graphite drawing by Kent Twitchell of fellow artist Charles White. White’s own drawing, Seed of Love is also included in the exhibition and is on view just a few feet away from Twitchell’s portrait of White. Unaware that I had entered the space since his back was to me, Cedric was completely absorbed, looking intently at Twitchell’s gigantic graphite drawing, which had been unrolled upwards from its wooden box, secured onto the wall. I was struck by the effect that this powerful and over-life-size image was exerting on Cedric. Rather gingerly I approached Cedric, not wanting to disturb him, yet wanting to let him know that I was in the room with him. Becoming cognizant of my presence, but still looking straight ahead at the drawing, Cedric whispered four words: "He was my mentor."

I was moved by Cedric’s emotional response to this drawing and thought it would be insightful to learn a little bit more from Cedric about the history of his relationship with Charles White (who he refers to interchangeably as “Mr. White” or “Mr. Charlie”) and his thoughts about Twitchell’s drawing. Little did I know how much more our conversation would teach me about one of the artists in Drawing in L.A. and about Cedric himself.

Claudine Dixon: How and when did you first become aware of Charles White?

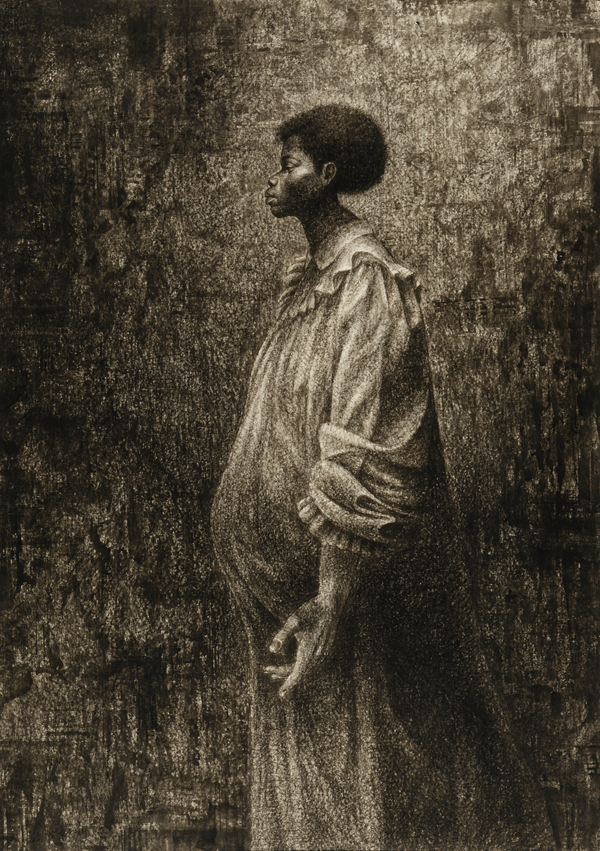

Cedric Adams: It was back in the ‘60s, during the time of the Civil Rights and Black Arts Movement. There was an awareness of “self” in the black community: “Black is Beautiful.” People wanted to see themselves. I had moved to Los Angeles in 1966. Mr. White’s works were reproduced and placed on bus stops, telephone poles, and made as posters to be seen by the public. He didn’t mind—he was glad to see his art disseminated amongst the people. This is one of the things he insisted upon when one of his images was purchased through the Graphic Arts Council at LACMA, the I Have a Dream lithograph of 1976, published by Cirrus Editions. Mr. Charlie wanted reproductions made available at an affordable price. I was thus aware of him and met him through his art.

CD: When did you then meet Charles White in person?

CA: At the time I wasn’t a practicing artist. My first formal art classes were in 1968 in high school and I was made aware of Charles White at Compton High School through Wes Hall, who was my first mentor. Hall was a former president of Art West Associates, Inc., a professional art group, created and founded by Ruth Waddy [LACMA’s collection includes Waddy’s sketchbook as well as a graphite drawing of Waddy by Cedric Adams]. Wes and I did a short video shoot on this for Unframed. I became aware of White in 1968 in Wes Hall’s art class. I met him in 1974 when he presented me with the first place graphics professional award when I exhibited at the Watts Summer Festival. In the fall of 1974 I was asked, as a representative of Art West, to present an award to Mr. White and William Hanna of Hanna Barbera Animation at a presentation at Compton College, where Hanna had been a student. I later worked at Watts Towers Arts Center, where artist John Outterbridge was director. I met Outterbridge when I was 17. In 1978, the artists Charles Dickson and Greg Pitts came by Watts Towers and said, “We’re going to see Mr. White. Wanna come with us?” And I said, “No, not now, I can see him later, he’s right up the freeway. I’ll catch up with you all later.”

You can’t take people for granted. Charles White died not too long after that day. I later learned how Charles, Greg and Mr. Charlie had visited one of White’s neighbors, Richmond Barthé, the Harlem Renaissance sculptor, and they had a wonderful time. The four of them together, can you imagine? And I had said, “No I’ll catch up with you later.” Jeez…both White and Barthé passed away soon after that.

CD: Do you know Kent Twitchell?

CA: I met Kent Twitchell, I cannot remember exactly when. But I’d see him out and about. I knew he was an understudy or disciple of Mr. White.

CD: The Los Angeles Times featured an article on Kent Twitchell earlier this month. Various future mural portrait projects were mentioned, including plans for a new Charles White mural to be installed on the wall at Charles White Elementary School near MacArthur Park. You knew Mr. White as a person. I look at Twitchell’s drawing and feel I can understand what that man was like. I can imagine what he sounded like.

CA: It gives me goose-bumps. Kent Twitchell was able to capture Charles as a teacher…well, it’s pure talent too. I’d say that he’s a disciple or understudy of Charles White, along with Kerry James Marshall and Richard Wyatt, Jr. Wyatt’s murals are all over the city, and his drawings, I think, are just a little more refined and detailed than mine [chuckle].

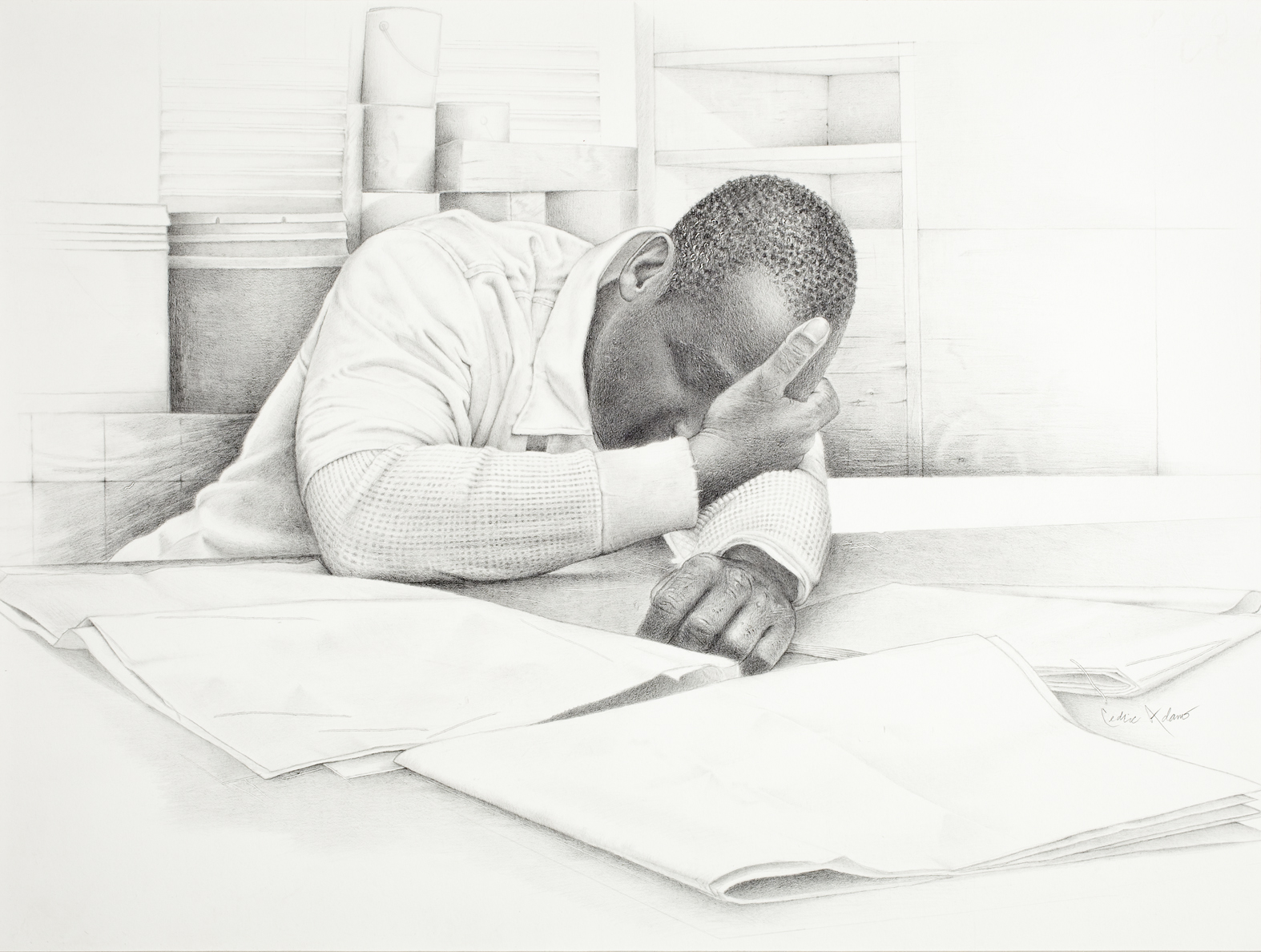

CD: What does your own art look like? Does it draw upon what you see in Charles White or Kent Twitchell, or is it completely different?

CA: How can I articulate my answer? I started art classes in high school, with two electives. French was one. The first thing I saw alphabetically was “art” under “A” so I took art class as my other elective. That was at the beginning of the semester. All the supplies had not yet arrived, so teacher Wes Hall said, “Just start drawing with a pencil until supplies come in.” I stuck with that pencil. Although I was probably first influenced by Charles White, I may have been influenced more by another American master, the late Raymond Lark. But from Mr. White, I tried to draw upon his strength. Charles White personifies “POWER.” There is strength in his drawing. It is technique too, but with the way he uses the light, there is something remarkable there.

CD: There’s a dignity to it. It takes your breath away.

CA: It gives me goose-bumps. I look at my work and I want that power. When Mr. White and Mr. Hanna spoke at that award ceremony at Compton College in 1974, Mr. White ended up preaching, really preaching. It was a verbal manifestation of what he does on the drawing board.

CD: It seems like Twitchell’s technique in doing things larger than life is perfect for conveying the spirit of Charles White.

CA: I don’t think there’s anyone more qualified to do this than Mr. Charlie’s former students, like Kent Twitchell. I didn’t know LACMA owned this drawing—I thought it was a loan for the exhibition. I had seen it once before with other large scale artist drawings by Twitchell when they were on loan to Otis.

I have four artist mentors in my life. Wes Hall, my art teacher, who was also my track coach at Compton High School. If you came into class too quiet, he would talk about you: “YOU’VE GOT TO SPEAK UP”—he worked on either toning you down if you were too loud, or making you talk up if you were too quiet, based on your personality. He didn’t want his students to be a clone of him—he wanted to help them discover who they were as individuals. He was a mentor to me by keeping my motivation going. I met Raymond Lark through Art West, I met John Outterbridge at the Communicative Arts Academy in Compton in February of 1971, and then I met Charles White. Those four were my mentors.

I didn’t want to draw exactly like them. I wanted to do it my way. Along the way I developed a technique that is uniquely mine. I would work with a pencil and the edge of the pencil wood would wear down if I didn’t sharpen it and in my zest and zealousness, it would scratch into the paper. That went on for maybe fifteen years. Then I stopped and remembered words of John Outterbridge, who was known, of course, for using found objects (like Noah Purifoy and Judson Powell). “Cedric, throw nothing away.” A light bulb went off, and I realized I can use that mistake and turn it around. I got a ballpoint pen with no ink and purposely etched into the paper. About ten years later I saw someone else working like that. But for a long time I saw no one else. My work was different by how I was doing it. But I’m not there yet. To get the strength and the power the way Mr. Charlie uses light—I’m not there yet.

.jpg)

CD: Your relationship to this drawing is so important and singular. The relationship you have with the artist, the person is unique and I wanted to give you the space to have that time. Spend some more time with this drawing while the show is still up. It is not something you can have a quick look at later. It takes some work to look at this drawing, both mentally and physically.

CA: I was sitting here and looking at it because it is not something I can just walk by and say, “Oh yeah.” It’s like a special gravy that has simmered for hours, it becomes refined, you savor it for those distinct thirteen or fourteen spices. You just don’t eat it—you dine. The same way those flavors wake up your taste buds, the same thing happens visually each time I look at this drawing. The coat, the hands, those glasses…The same way his work is strong and powerful, I am immediately brought into the presence of the man and who he was. Kudos to Kent Twitchell for conveying that. He knew the man, and I had met him. That came first. The awareness of his strength conveyed then an awareness of the technique, which followed.

CD: That’s a wonderful observation. You are one of the truly lucky people who have that experience. That’s definitely a gift.