Unlike languages written with phonetic alphabets, such as English, comprehending written Chinese characters relies more heavily on visual-spatial processing areas in the brain. In other words, for a speaker of English to read and comprehend written Chinese, the reader must be trained to engage an entirely separate area of the brain in addition to what would be used to read a sentence in English. Looking at Xu Bing’s characters, however, reconfigures the most basic language-processing functions in the brain for speakers of English and Chinese. The Chinese-speaker will recognize the character as an image, a familiar ideogram, and attempt to decipher it as such, only to find that the strokes have no meaning because they are composed of Roman letters. The English speaker will approach Xu Bing’s Rise Free from Care (2009) with the immediate assumption that the characters are foreign and incomprehensible, yet, upon closer inspection, will realize that Xu Bing’s ideograms are instead a reorganization of familiar letters into readable words.

Xu Bing’s work forces the hybridization of these two languages in such a way that confuses communication and understanding through both. At the same time, even with this deliberate misuse of the written form, the resulting crossover does not exclude based on knowledge of one language or the other. Rather, Xu Bing incites an investigative, curious reaction in all of those who take a few seconds to really look. His work allows the inherent differences in how speakers of different languages process the written form to shape how they experience his art.

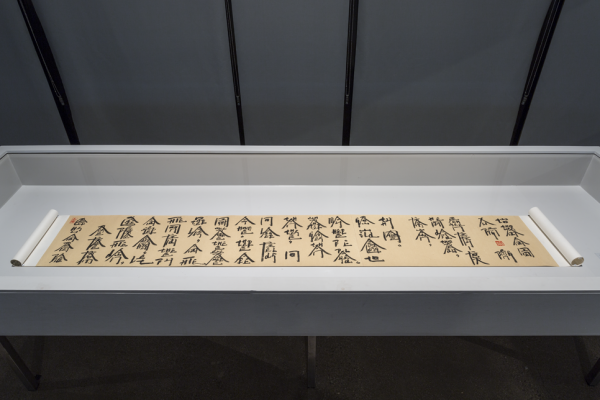

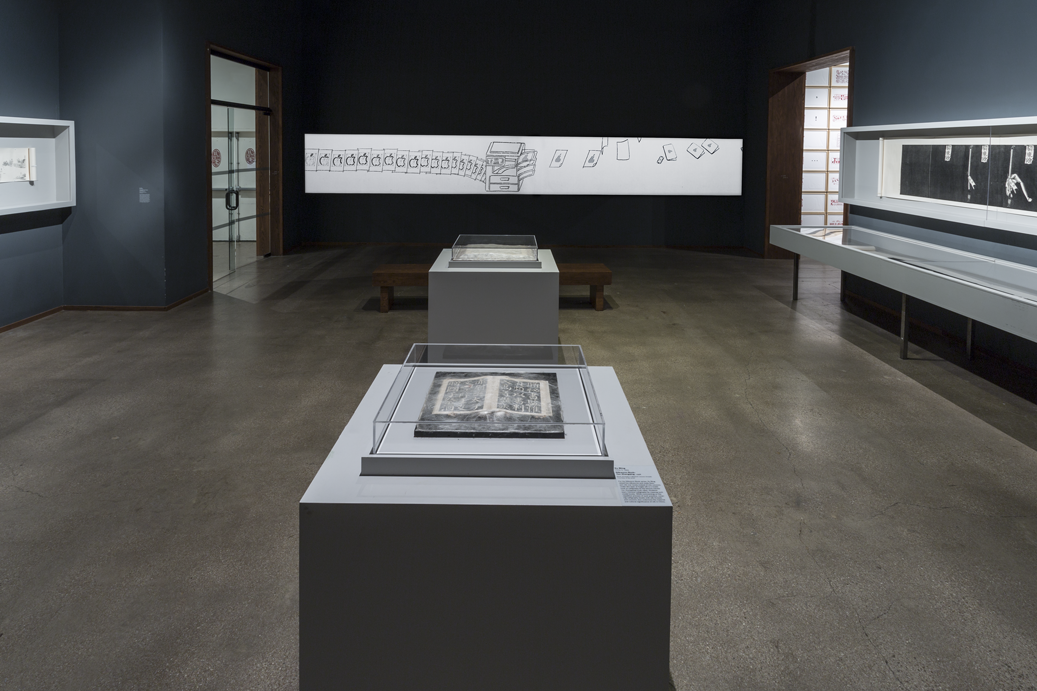

Regardless of how we approach an individual work, calligraphy remains a constant in the exhibition. Xu Bing conveys calligraphy as visual art, as writing, and as cultural symbol, all often within a single work of art. Highlighted works such as the Silkworm Book (1998), which investigates the significance of silk and paper as mediums in practicing calligraphy, it is through this kind of exploration of the many layers and channels through which meaning can be expressed that calligraphy attains its prominence within the exhibition, and within Xu Bing’s broader practice. The copying of the Tang dynasty master calligrapher Yan Zhengqing connects Silkworm Book to a tradition of imitation of the masters in Chinese fine art practice, integrating another perspective for interpretation. The video Character of Characters similarly references Chinese art historical tradition—as explored in depth in Wan Kong’s essay— and continues the presentation of calligraphy in such a way that language becomes an invitation to rethink a known language (or languages) beyond their sole communicative function. In these works, the multi-faceted significance of calligraphy in Chinese art expands to accommodate and engage a truly international audience. No matter what language one speaks, or how Xu Bing manipulates his brush to confuse written communication, the exhibition maintains the high aesthetic value of calligraphy as a visual art—every visitor can appreciate the beauty of the artist’s calligraphy.

Despite grand claims of Xu Bing’s work creating a universal language, LACMA’s exhibition (and arguably the artist’s work in general) does not invoke immediate, visceral, intense reaction—nor, I think, is that the aim. Communication between art and audience is at once international, because of the increasingly widespread use of English, as well as the rising importance of Mandarin Chinese, yet deeply personal to the artist, who has lived in the United States and experienced language barriers first-hand.

The artist’s ability to focus on language as universal communication, while translating his own experiences living in a globalized world, fits in almost perfectly with the constant talk of globalization and transnational movements in contemporary art. This ability has therefore allowed Xu Bing to become a widely recognized and highly acclaimed contemporary artist, particularly among his contemporary Chinese artist peers. But with Xu Bing’s art, there often remains the initial assumption that this is the kind of Chinese art one would expect in a museum, a deception of his audience (Chinese or not) that differentiates Xu Bing’s practice from the experimental pioneering of much of contemporary Chinese art. Compared to the energetic, intensely critical works of other contemporary Chinese artists of Xu Bing’s generation—with Ai Weiwei or Wang Guangyi likely the first to come to mind—Xu Bing’s art is quiet. At the same time, his work inspires thought and contemplation on the part of his audience, from the simplest realization that what one sees is different from what one expected to see, to the invalidation, and subsequent confusion of, the processes that we all use to communicate.

In this exhibition particularly, Xu Bing questions what it means for art to be Chinese using the most traditionally Chinese of mediums and formats, such as handscrolls, ink, calligraphy, silk, and woodblock prints. In light of the rise of a younger, so-called post-Mao generation of contemporary Chinese artists, who often challenge the search for what is “Chinese” about their work, or themselves, Xu Bing subtly, yet powerfully, inserts himself into that dialogue. He is wildly experimental, but he works with long-standing traditional mediums. His works speak for themselves; his calligraphy inspires wonder, awe, and introspection. And that is the beauty of this exhibition, that in this intimate space we are invited to experience truly great art through our own means of understanding, or, in keeping with the exhibition’s title, art that we can understand through our own language.

The Language of Xu Bing is open through July 26 in the Hammer Building.