It’s a strange thing to be invited to rifle through someone else’s mail, to litter it with alphanumeric sequences, to conceive of descriptive titles for innocuous (though somewhat mangled) envelopes, and to restore said articles of postal communication to their proper protective sleeves, sandwiched between gossamer-like sheets of glassine and finally housed in sturdy, acid-free boxes. This is an especially odd task for a student of the Middle Ages, a period during which paper was considered a novelty and correspondence was transferred by means of lone, stalwart horsemen. Thus, when charged with cataloguing the feedback received in response to Eleanor Antin’s series of 100 Boots postcards—a project carried out between 1971 and 1973—I felt out of sorts and positively medieval. Upon further acquaintance with LACMA’s collection, the archival material transformed from intimidating and foreign to intriguing and delightfully inscrutable.

But first, a bit of context: during those early years of the 1970s, Antin embarked on an extended journey with her 50 pairs of trusty boots. She staged the boots in various settings across California and had the whimsical photographs fashioned into postcards, which were then distributed to all manner of folk from the art world and beyond. The response was staggering—to the extent that the letters, art pieces, change of address cards, and exchanges with museums like the Met and the Whitney now occupy 14 boxes in LACMA’s archive. Most engagingly, the contents of the boxes read like a capsule of those critical years of the mail art movement. The collection is replete with specimens by mail art luminaries such as Ray Johnson, John Evans, Glenn Lewis, and Fletcher Copp, among others. All these names were entirely unfamiliar to me at the outset of my fellowship, as can only be expected from someone more intimate with the roster of Catholic saints than with the living, breathing artists practicing in our contemporary world.

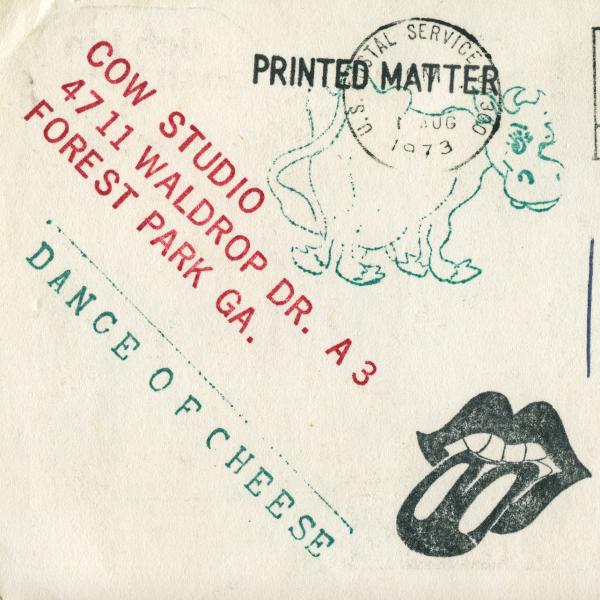

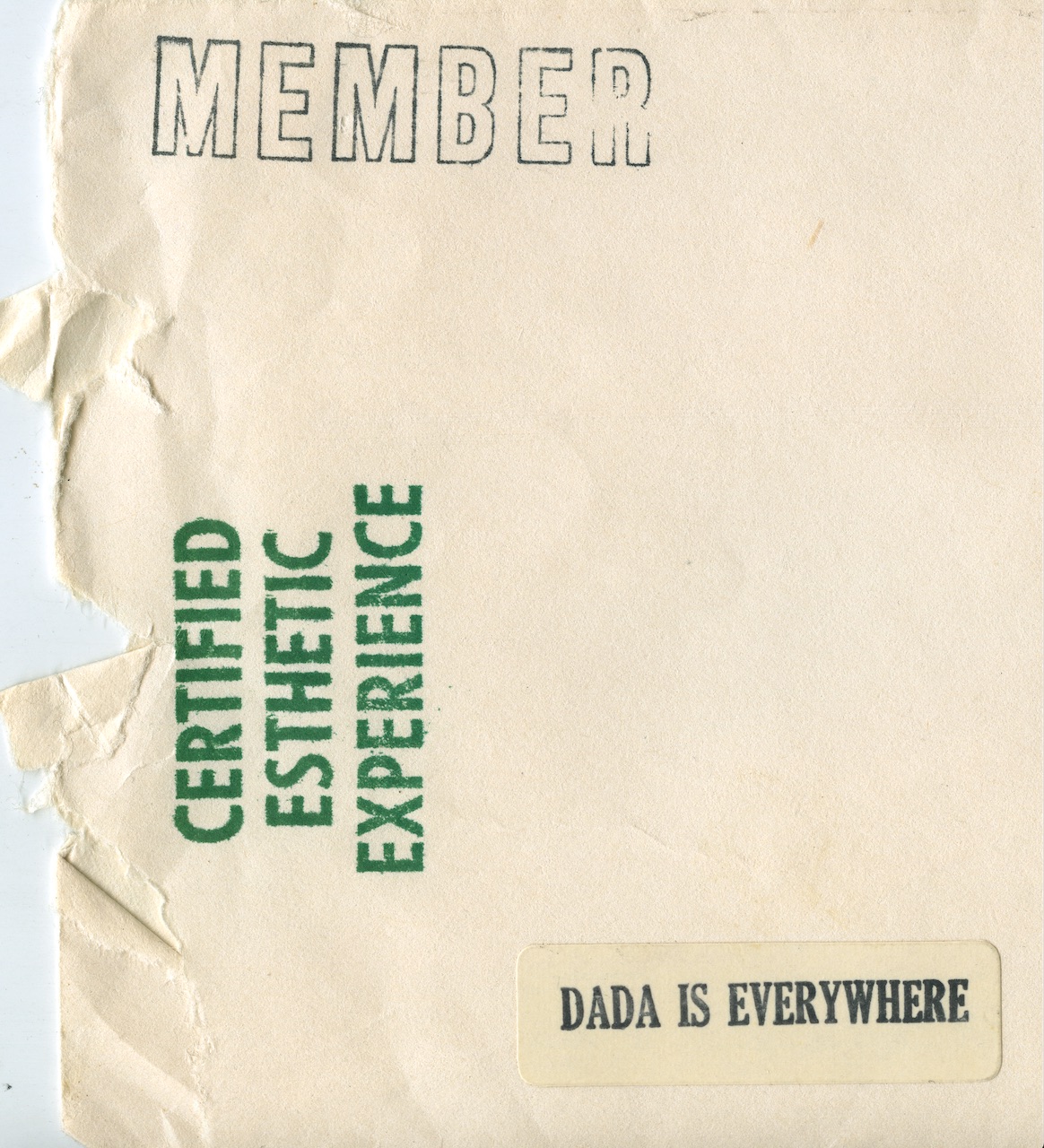

In spite of my (seeming) disciplinary and temporal isolation, I was soon entranced by mail art and its ethos of democratizing the conventional channels of artistic dissemination, even more so by its rather prescient enactment of a global network, one in which identities and communal sensibilities could be fostered in the complete absence of face-to-face interaction. I was especially taken with the repeated and lively use of stamps. In their essay “The Stamp and Stamp Art” (found in the 1984 book Correspondence Art: Source book for the Network of International Postal Art Activity), critic Georg M. Gugelberger and mail art practitioner Ken Friedman assert that the advent of the rubber stamp “coincides with industrialization, mechanical reproduction and the rise of the modern nation state.” Its creative usage in the arena of mail art could therefore assume any number of associations, be they cultural, political, metatextual, or what have you. Mostly, I saw the stamps as coded winks from one mail art co-conspirator to another, bearing enigmatic messages such as “CERTIFIED ESTHETIC EXPERIENCE,” or, a personal favorite, “DANCE OF CHEESE.”

What was certainly not lost on me was the impression that these perhaps diminutively called “ephemera” actually constituted and reconstituted the “primary” work of the postcards. Belonging to an idiom where “send and ye shall receive” was the modus operandi, Antin’s feedback grew weightier by the box. So, out of the box and into the vitrine?

A selection of items from the “100 Boots Feedback” collection is now on view at LACMA’s Balch Art Research Library, open to the public by appointment from 11 am to 4 pm Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday.

Rachel Daphne Weiss is a graduate student specializing in medieval art and architecture in the UCLA Department of Art History and a 2015 fellow of the UCLA-LACMA Art History Practicum Initiative.

To make an appointment with the Research Library, call 323 857-6118 or email library@lacma.org.