In December 2014, when the Whitney Museum of American Art contacted Stephanie Barron, LACMA’s senior curator of Modern Art, to inquire about the possibility of including Frank Stella’s St. Michael’s Counterguard in their upcoming retrospective, she was hesitant, and for good reason. The artwork, which had been damaged from previous loans to other museums many years ago, was not in good shape. Much conservation work needed to be done and new crates would need to be fabricated to protect the artwork during travel. All of this would be costly. In the end, LACMA saw it as an opportunity to finally restore this wonderful work of art and there was no excuse—the Whitney stepped up to the plate and agreed to pay the crating costs, which were substantial. And Frank Stella, an icon of postwar American art, would be there. The deal was done.

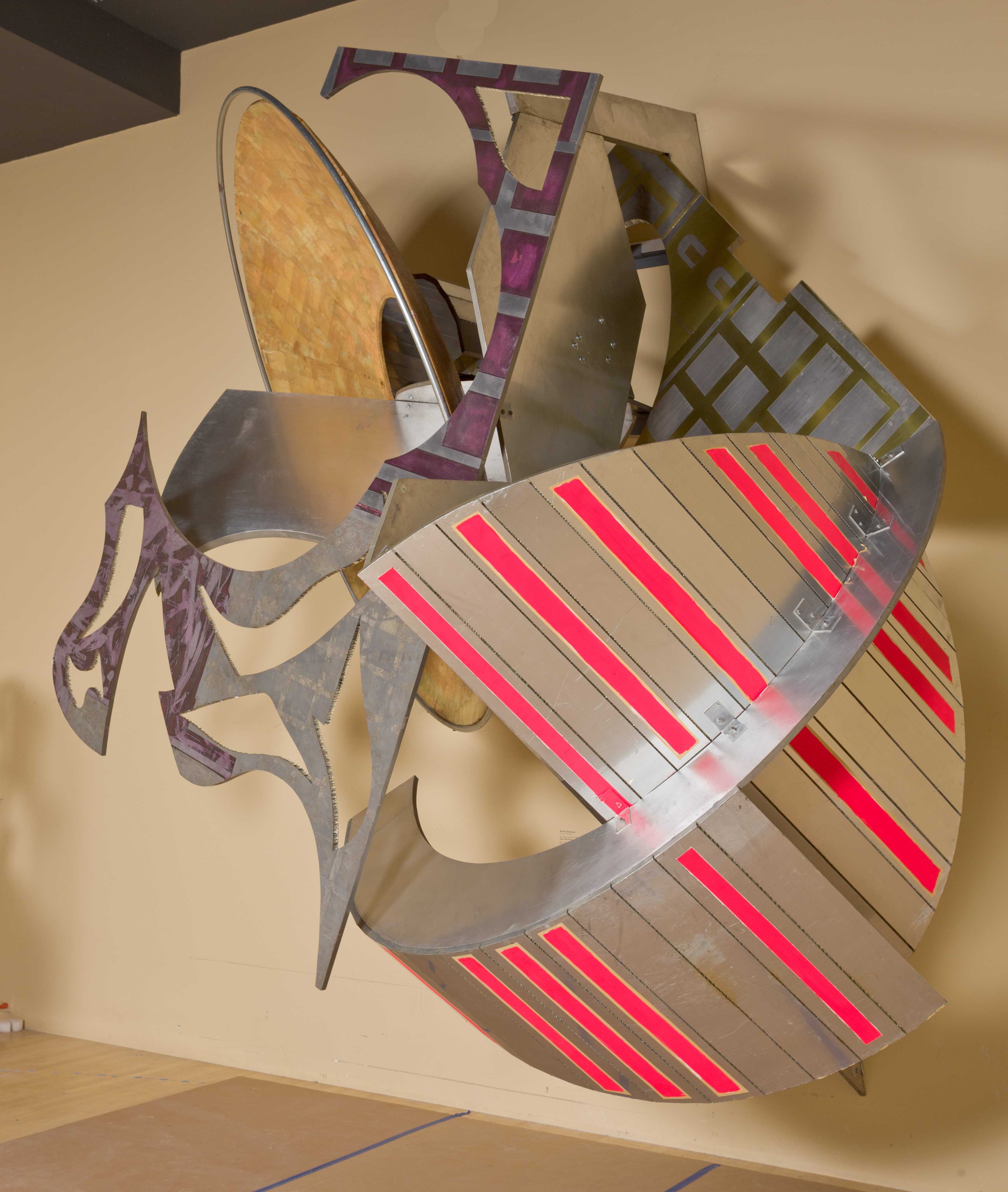

In the 1980s and '90s, Stella turned away from Minimalism, and the deep reliefs of his paintings gave way to monumental multi-colored wall reliefs and sculptures made from metal and decorative architectural elements. One of the earliest works in this new genre is Stella’s St. Michael’s Counterguard. Fabricated in 1984 and acquired later that year by LACMA (gift of Anna Bing Arnold), the sculpture is literally impossible to describe in words. It consists of honeycomb, aluminum sheets of various shapes and sizes decorated with stencils, connected together as one unit projecting outward from the picture wall, suspended in mid-air from a single cleat. Last shown at LACMA in 1989 where it was placed on exhibit following its return from loan to Museum of Modern Art in New York, the museum’s institutional memory of the current condition of the artwork largely resided in the Conservation Center’s long time conservator, Don Menveg. Not having seen the artwork in over 20 years, his recollection of St. Michael’s Counterguard was that “it’s a difficult installation.”

With some apprehension, conservators pulled the artwork from storage and opened the crates. Yes, all the parts were there (with the exception of the original wall cleat), but could we put them together? The only way to make sure was to temporarily install the artwork ourselves at LACMA before repacking and crating it for transport to the Whitney. Easier said than done, given the need for a vacant wall space big enough to accommodate an artwork that is over thirteen feet tall, eleven feet wide, and nine feet deep. After several months of looking at both public and non-public spaces throughout LACMA’s campus, including underneath exterior overhangs in the Ahmanson Building, a suitable space was found in one of the empty galleries in the Arts of the Americas Building that was undergoing renovation. There, the sculpture was cleaned, the correct sequence of installing the interlocking cutout forms was confirmed, and missing or damaged hardware was replaced and repaired.

Due to the complexity of the installation and the fragility of the artwork, Don traveled to the Whitney to supervise its installation by the museum’s expert art handling staff. As you can see, it went without a hitch under the watchful eye of the artist himself.