Dedicated to bringing an international group of artists into LACMA’s collection, Contemporary Friends was formed in 2013 by LACMA trustee Viveca Paulin-Ferrell. In the last four years, Contemporary Friends has helped the museum to successfully acquire 29 works. This year, the acquisition group gathered to discuss a diverse group of works proposed for acquisition, then voted on which works would enter the collection. Below is an overview from this year’s acquisition; also check out highlights from 2015, 2014, and 2013.

Piero Golia has lived and worked in Los Angeles since 2003 and in that time he has ostensibly become the padrone of the Los Angeles art world. His presence is acknowledged most directly with his installation on top of the Standard Hotel on Sunset Boulevard: appropriating the bright-light vernacular of the city, a large glowing orb is lit up only when the artist is in town. With artist Eric Wesley, Golia conceived of, founded, and continues to run the highly selective and tuition-free Mountain School of Arts. One of Golia’s most recent projects was Chalet Hollywood, a space for gatherings and conversation that featured commissioned works by artists including Pierre Huyghe, Jeff Wall, and Mark Grotjahn, as well as a range of unexpected occurrences including a marching band, acrobatic performances, and an alpaca zoo.

Elements of humor, interference, and mythmaking characterize Golia’s varied artistic contributions. He has climbed up a palm tree and stayed there until a collector agreed to buy his work; rowed across the Adriatic Sea, becoming the first illegal Italian immigrant to Albania; and received the invitation to do his first exhibition with Gagosian Gallery after he had already announced the opening date on Facebook. With a tongue-in-cheek impetus to disrupt the accepted order of things, he challenges the economy of the art world by interlacing it with personal narratives of both optimism and disappointment.

Studio is a bronze cast of Golia’s fictionalized and nonexistent studio in miniature scale. Without one of his own, Golia came to understand that a studio is more than a workspace; it is a means to create a narrative for one’s practice. He started to build his first studio maquette using cardboard and toys, which he updated daily from his living room so at any time it reflected all of his works in production, even if works appearing side by side were in reality separated by hundreds, if not thousands, of miles. Over time, the model evolved into a sort of mania and Golia started simulating reality down to the smallest detail. It was at this point that he decided the ultimate gesture would be to cast it and eventually put his privileged and private workspace on the market.

Instead of using the inexact process of poured bronze, Golia worked with an expert who plated the mold with thin layers of copper that absorbed its every detail. The bronze casting involved 210 pieces that were then welded together. By assembling a number of discreet artworks in one place, this single work provides an overview of the artist’s career. “This work is way more than just itself,” Golia says. “With one work you cover a huge span of my career...so economically, it’s a great deal.” Created just before Golia participated in the Venice Biennale in 2013, the cast was an attempt to freeze time so that Golia could remain in a continual state of anticipation, rather than having to confront the reality and disappointment of this milestone. Though Golia continues to work with a foam and paper studio maquette, this is the only bronze he has made. This is Golia’s first work to enter LACMA’s collection.

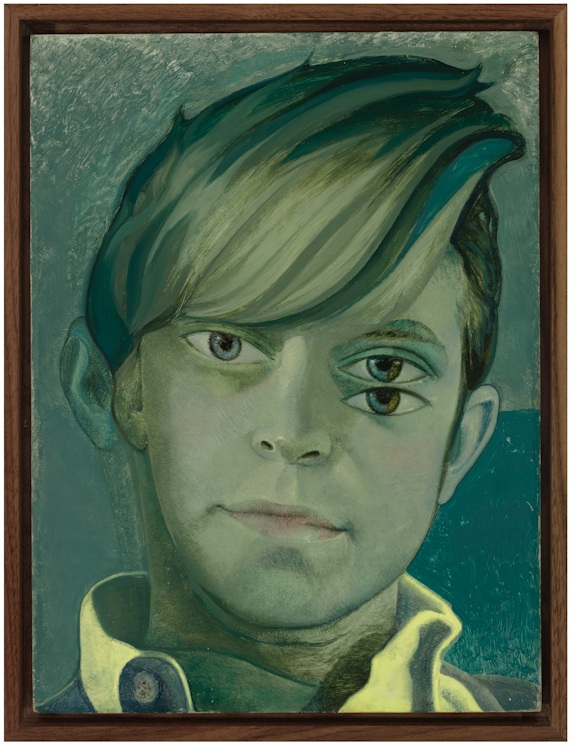

Victor Man’s mesmerizing paintings resist easy interpretation—he intermingles literary references, media sources, as well as his own biography. Man’s constellation of images includes portraits and still-lifes as well as occult-like and erotic subjects. In his work, animate and inanimate, human and animal, and male and female appear to be in constant exchange and fusion, leaving the viewer aware that a shift in meaning is still possible. Influenced by contemporary photography, Man’s closely cropped compositions further obfuscate his subject matter while his layered compositions reveal his technical prowess. With their finely applied layers of paint, the surfaces create a rich threshold between the reality of the viewer and that of the painting. Grafting/ or Lermontov Dansant Comme Saint Sebastien is miniscule, but its slight size does nothing to take away from its impact; even in a compact space with a seemingly straightforward subject, Man creates a welcome state of dreamlike disorientation. The scale is that of a sacred, talisman-like object, a portrait of worship, of romantic love. The face depicted—with his falling or refracted eye—is both a double portrait and a self-portrait: the artist’s self-portrait with that of a past love. Upon inspection, variances in technique as well as seeming miscalculations in the composition convey the two-ness of separate individuals, merged but not with exactitude. A flop of hair seems suspended over the head, as if it is too large for its cranium, and the eye on one side is crystalline blue, while the other two carry a weight of brown across them. Simultaneously visceral and barely there, the painting engages in a precarious seesaw between presence and absence.

In 2014, Man was awarded Deutsche Bank’s “Artist of the Year” prize. His work has been the subject of solo exhibitions in Haus der Kunst, Munich; the National Gallery of Art, Warsaw; and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, among others. He was most recently included in the central pavilion of the 56th Venice Biennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor. This is Man’s first work to enter LACMA’s collection.

Since the 1980s, Vancouver-born multimedia artist Stan Douglas has used history and place as muses for his films, photographs, and installations, often enlisting new as well as outdated technologies in his time-traveling works. Douglas’s monumental film, Luanda-Kinshasa, presents an aural essay on jazz as an expression of the black consciousness of the 1970s. The setting is imagined in the landmark Columbia 30th Street studio, which witnessed among the most pivotal, genre-spanning recordings until its closing in 1981. Artists who came through the studio include Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Pink Floyd, Johnny Cash, Billie Holiday, and Aretha Franklin. Douglas expands his interest in the African origins of the music scene in New York and the seismic global changes that took place in the 1970s, specifically the creative production in an era of mass culture. Luanda-Kinshasa documents a fictitious recording at the famed studio, featuring a band of professional musicians improvising together. Details of the performance serve as an investigation rather than a prescribing thesis; the ethnicity of the band members, the gender dynamics in the band, and the fashions on display create a space and time for broad-reaching ruminations on the transitional nature of 1970s. Curiosity in synthesizing sounds and genres, as well as an affinity with Afrobeat, are reflected in the musical variations that take part during the six-hour-and-one-minute performance, during which multiple permutations of two improvised songs titled “Luanda” and “Kinshasa” are played.

Similar to Douglas’s previous films involving arbitrary loops that take days to unfold, Luanda-Kinshasa defies a linear expectation of narrative in favor of the compositional process itself. Over the past decade, Douglas’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at museums and institutions worldwide. In 2012, he received the prestigious Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography, New York. Douglas was recently the recipient of the third annual Scotiabank Photography Award in 2013. The first work by Douglas to enter LACMA’s collection, Luanda-Kinshasa was jointly acquired with the Perez Art Museum Miami, where Franklin Sirmans, formerly LACMA’s Terri and Michael Smooke Curator and Department Head of Contemporary Art, is now director.

Hayal Pozanti was born in 1983 in Istanbul, Turkey, and received her MFA from Yale University in 2011. Her work takes a variety of forms—paintings, sculptures, collage, and digital imagery—in order to navigate the intersections between new media technologies and the handmade. Pozanti’s paintings, such as Charms In The End (2013), feature imagery that is generated through a combination of hand-drawing and Photoshop, an abstract language of symbols painted in acrylic on panel with the proportions of an iPhone 5. The symbols are arranged in different configurations, their standardization undermined by the whimsical depiction, with irregular edges painted in warm tones and unexpected pops of color. Pozanti’s paintings are a hermetic, introspective system that uses abstraction rather than appropriation to respond to the hyperconnectivity and image saturation of a globalized culture.