Inspired by historical objects, Michael Eden combines new technologies with traditional craft skills to create illuminating works of art that explore visual perception and the relationships between two- and three-dimensionality. I invited him to consider the design legacy of the Stowe Vase, a monumental marble antiquity in the museum’s collection, and create a new work for the exhibition The Stowe Vase: From Ancient Art to Additive Manufacturing.

Following the arrival of Michael’s work at the museum, I asked him to share his thoughts on the commission from the comfort of his studio in England’s picturesque Lake District. Audio extracts from this conversation, accompanied by images of Eden and the stages in his creation of the Innovo Vase, now appear in the exhibition beside the finished work. What follows is an expanded version from our recording session with LACMA vice president of technology & digital media, Amy Heibel.

How would you describe your practice?

I would describe myself as a maker rather than what I used to be, which was a potter, for 25 years or so. I call myself a maker because it allows me to explore the sort of gray areas in between art, design, craft and technology.

Did you gain specific insights from researching the history of the Stowe Vase?

I found contradicting stories, one being that it wasn’t an original vase—it was something that the Italian etcher and sculptor Giovanni Piranesi had created. Other information alluded to the fact it had been reconstructed from parts that had been excavated from Hadrian’s Villa in the 18th century. I was on a bit of a detective hunt. And, during that process, I was becoming more and more interested in the work of Piranesi, and the fact that, in looking at these objects in museums, perhaps you’re not looking at quite what you think you may be looking at, and that there are lots of really fascinating stories attached to these objects.

What were your overall goals for the LACMA commission?

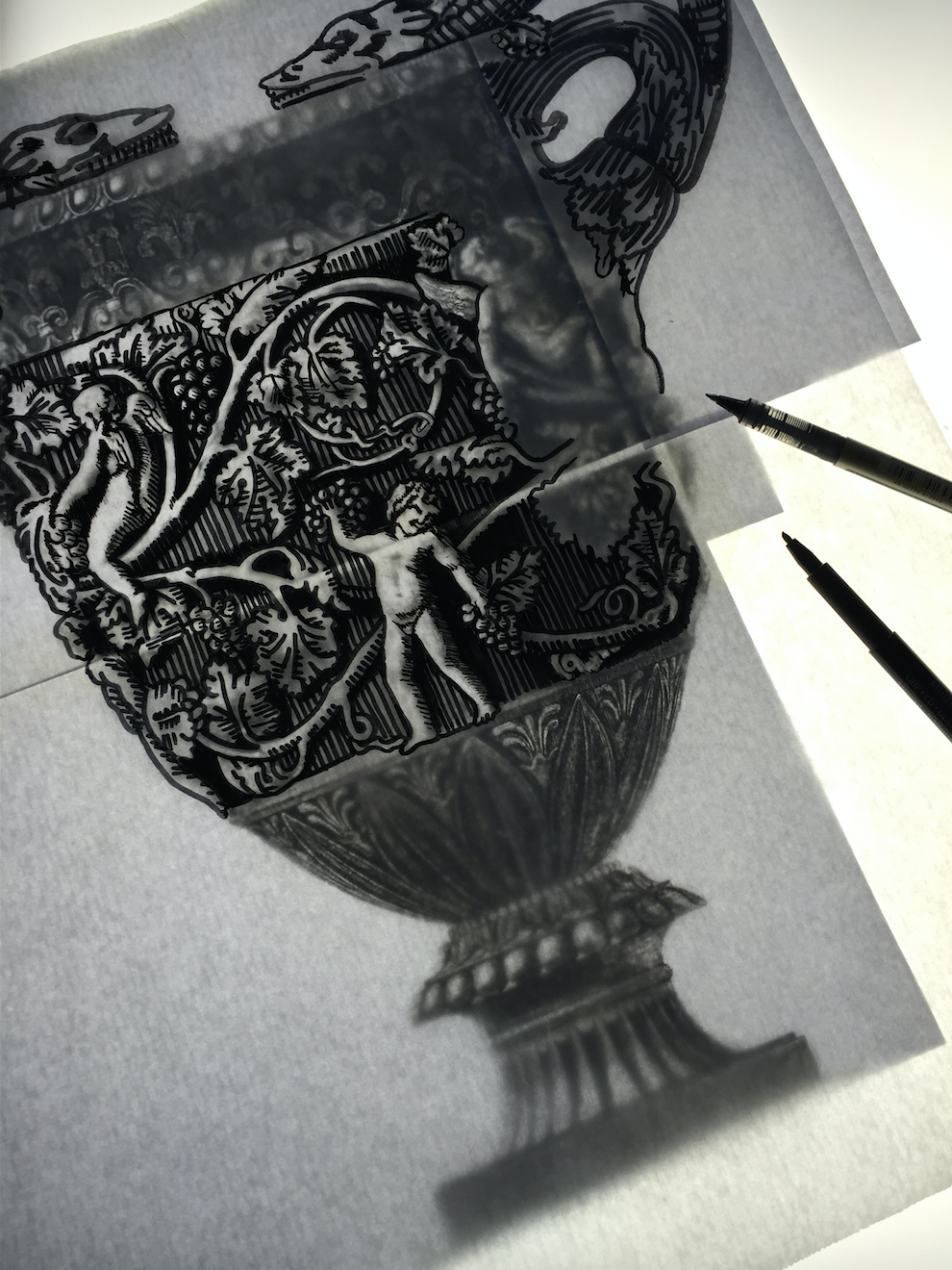

My goal in the recreation of the Stowe Vase was not to try to reproduce it, but to reinterpret it—to bring it into the 21st century, based on the way that I have been working for the last 10 years or so, using new tools which are becoming increasingly available. I was particularly interested in Piranesi’s etchings of it. There’s a strong resonance between the 2D etching process and 3D printing, so it was an opportunity to continue my exploration of the relationship between 2D and 3D.

How do you start to work on a piece?

I actually start with my sketchbook—in which I write notes, collect information and images that I’ve been sent, or images that I’ve found—and I “doodle” to explore this material I’ve gathered. But very soon, I move over to the computer, and I employ 3D CAD [computer-assisted design] software, which allows me to draw objects in three dimensions. But the idea leads the way, and always starts in the sketchbook, and then moves over, in a fairly formed state, to the CAD software.

I don’t let the tools dictate the outcome of the piece. 3D printing—it’s fashionable, it’s cool. But it’s only a tool, it’s only technology, it’s only the same as a sophisticated hammer or a chisel. It’s what you use it for that’s important.

What stages did you go through in designing the Innovo Vase?

Initially, I used the CAD software to create a simplified version of the main features of the Stowe Vase that would act as a framework on which I could apply the much more detailed decoration. I then reinterpreted the Piranesi etchings, taking into account the 3D printing technology that will only allow a certain minimum thickness of material. Any detail that was going to be less than, say, 1.5 mm wide had to be excluded. Taking a small section, in the CAD software, I extruded this, turning it from a 2D image into a 3D form, and I used that to cut through the simplified version of the vase I’d previously constructed. I spent probably the next four weeks very, very carefully extruding each section of the drawing, and cutting through the vase shape to create the “blueprint” to produce what you see in front of you today.

The selection of the color came quite late in the day. Because I’d been looking at the Piranesi etchings for days and weeks, I thought I should create my interpretation of the Stowe Vase to reflect them. The natural color was therefore a matte black. I also thought that the black would enhance the piercing and the three-dimensionality of the piece.

What was it like to finally see the real, finished work?

I’d spent five or six intense weeks staring at the screen until the design work was completed. Even though I’m looking at a virtual 3D object on the screen, and can explore it in the minutest of detail, it’s not the same as engaging with a real object. That’s why I think it’s important to have been a potter, to have made ceramics for 25 years, before evolving my practice to the use of these new technologies. When I’m looking at objects on the screen, I’ve got to imagine what they’re going to be like in real life.

But even so, seeing the Innovo Vase for the first time, when it came back a couple of weeks later, was an absolute revelation. I carefully unpacked the box when it came, and it was like Christmas. It was just more—much, much more—than I ever expected. I was really pleased that we created a piece that does look really imposing, far more imposing than it looks on the screen.

What does the title mean?

The decoration of the Stowe Vase incorporates snakes, and vines, and grapes [which are all Bacchic symbols]. Bacchus, in Roman mythology, is associated with dying and rebirth, and it seemed to tie in with the history of the Stowe Vase—that it had been buried at Hadrian’s Villa, it had been excavated, it had been restored, it had been reinterpreted once or twice during its history, and now it was being reinterpreted again. In Latin, innovo translates as renew, or innovate, or start again, or return. So I thought it was the ideal word.

Michael Eden will be chatting about his work with LACMA curator Bobbye Tigerman in LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab tomorrow, June 21, at 7 pm. Following the conversation, Rosie Mills will lead a tour through The Stowe Vase: from Ancient Art to Additive Manufacturing. The event is free, reservations required.