As a medium of self-expression and a foray into certain social circles, men’s fashionable neckwear—the cravat and its descendant, the tie—has long been a signifier of identity. During the 18th century, the stock, jabot, or cravat, often of fine linen, served to effortlessly elongate the neck to accentuate the fine silk textiles that made up a gentleman’s suit. The 19th-century cravat was the “face” of an ensemble manifested in a meticulously prepared and tied bow or knot, and the 20th-century tie added an inflection of the wearer’s personality in the form of a flash of color and pattern to a staid business suit.

In 1828, H. Le Blanc observed the significance of neckwear in his treatise, The Art of Tying the Cravat, stating:

When a man of rank makes his entrée into a circle distinguished for taste and elegance, … he will discover that his coat will attract only a slight degree of attention, but that the most critical and scrutinizing examination will be made on the set of his Cravat. Should this unfortunately, not be correctly and elegantly put on—no further notice will be taken of him…”

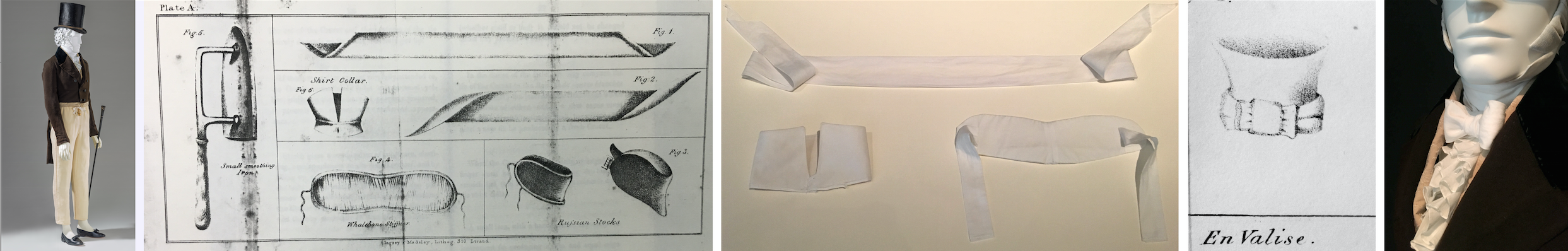

Le Blanc’s advice guided and inspired the dressing of 131 full ensembles in Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715–2015. The 1820s dandy ensemble is reminiscent of the styles idealized by that of Englishman Beau Brummel. The recreated neckwear, informed directly from LeBlanc’s manual, includes a standing shirt collar and a collar stiffener (made of whalebone in the period, but here of buckram). After practicing the Nœud Gordien, the simplest knot in the manual, and looking at fashion plates, I transformed the cravat into a simple low bow tie, similar to the Cravate en Valise knot depicted in the book. The high, firm stiffener gave a base for the wrapped, traditionally linen cravat, here made of fine cotton (fine linen weaves are hard to find in today’s marketplace) with a hand-rolled hem, and acted to elongate the neck.

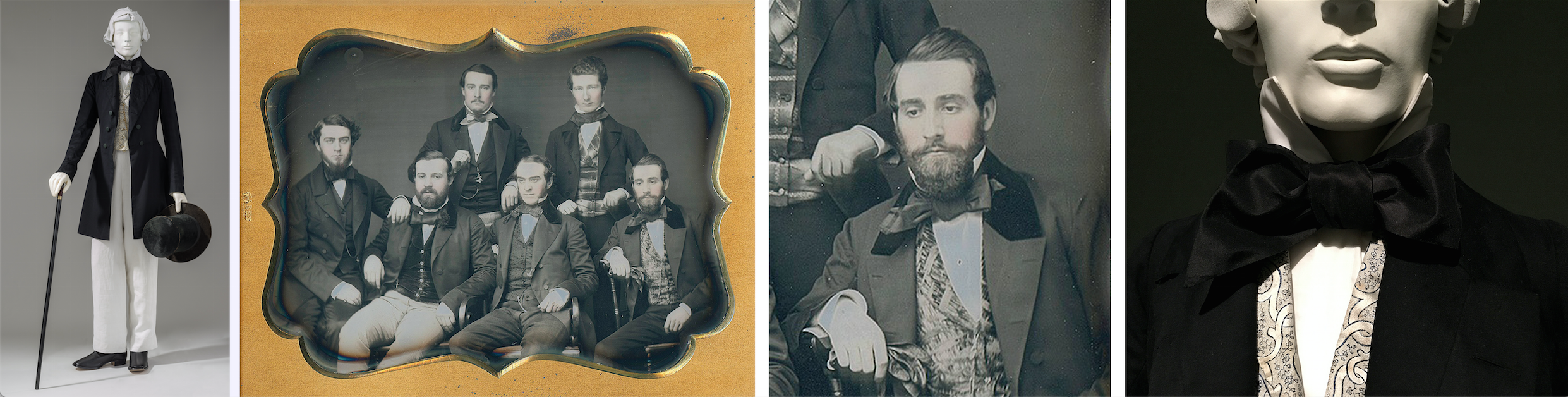

Accessorizing ensembles with neckwear took thoughtful consideration. During the 300 years covered by the exhibition, the cravat and tie, or the omission of one, was an integral element in conveying the social status and individuality of the wearer. Furthermore, tie styles followed the prevailing fashionable silhouette and were a crucial component to balance the overall appearance of an ensemble. For example, the large bow tie popular in 1850 countered the hourglass silhouette of the period’s full-skirted jacket. The frock coat, circa 1852, represents the hourglass silhouette fashionable to that period. The daguerreotype, used as inspiration for the look, shows six young men with oversized bows tied around their necks. The width of the bow balances the width of the jacket’s skirt and took on many forms—from loose and jauntily tied, to straight and tidy. Ours, reproduced in a black silk satin, was tied in a bow with one side asymmetrically tied with one end left at its point.

Many of the ensembles in Reigning Men used neckwear from our prop or permanent collection. Although LACMA’s permanent collection of men’s neckwear is strong, many of the ties are too fragile to be exhibited on mannequins or weren’t exactly correct for the ensemble being accessorized, due to the textile or the occasion and time of day the ensemble was worn. Several neckwear pieces were carefully reproduced from primary sources, such as manuscripts, books, paintings, fashion plates, daguerreotypes, photographs, and extant examples in LACMA’s permanent collection. For example, the brown frock coat ensemble, circa 1840, was extensively researched by assistant curator Clarissa Esguerra, who styled the ensemble as an informal dinner suit. I conducted further investigation into the neckwear that would be appropriate for this time of day, researching tie color, materials, and shape in period fashion plates and journals. It was revealed that pastels in silk were commonly used for this occasion, and a diamond pattern was also often pictured. After sourcing and purchasing a modern textile that could approximate the period —a yellow silk self-patterned satin cut on the bias to form the diamond pattern—I used an extant example from LACMA’s permanent collection as a guide for the pattern, and this ensemble was accessorized with a stock-style bowtie.

Other examples of neckwear in the exhibition include one attached to the wig. The bag wig, with attached pouch at back, had ribbons that wrapped around the front of the wearer’s neck. More strictly considered part of the wig, it was treated as an accessory to emphasize the neckwear. Depicted in period paintings and drawings, the ribbons of the bag wig were illustrated using a variety of styles, often loose or tucked into the jacket, with their black hue setting off the white cravat, shirt ruffles, and lace. In Reigning Men, we tied the ribbons in a variety of ways to animate a sense of individuality in each ensemble.

The red and purple silk smoking ensemble, circa 1880, also has a tie recreated from an example from LACMA’s permanent collection, and an image found in a historical periodical. The dark black satin, a more subdued choice, balances the brightly colored suit.

The complex task of mounting menswear on historically accurate mannequins is not complete without thoroughly researched neckwear. Today, neckwear is often optional. A decision to exclude a tie, even in formalwear, can be a statement of one’s personal taste or a mandate of the designer’s vision. A contemporary suit by Alexander McQueen, Spring 2010, shows the absence of a tie, in order to respect the designer’s original look, and results in a casual interpretation of a traditionally formal style.

One blog post cannot include the very many neckwear styles fashionable through the past 300 years—come by to view these and others in Reigning Men, on display until August 21.