Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, the recent HBO documentary on the life and work of Robert Mapplethorpe, starts and ends with archival footage of the controversies that made him a household name shortly after his death from AIDS at the age of 42. For anyone unfamiliar with the events, here is the Cliff’s Notes version: in 1989, the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., canceled an exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s photographs that had already been shown in Philadelphia and Chicago without incident. The museum had made such a drastic move in response to threats from Jesse Helms, a senior senator from South Carolina, who had used Mapplethorpe’s images as Exhibit A of the scandalizing art being shown in American institutions with the support of federal funding. (He also famously attacked the work of Andres Serrano, particularly his 1987 photograph Piss Christ.) Despite—or perhaps in spite of—the hiccup at the Corcoran, the exhibition The Perfect Moment continued its tour, landing at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati a few months later, where local law enforcement officers presented the director with obscenity charges the very day the show opened. He was acquitted of all charges after a week-long trial, but the episode rattled the art world and remains a frightening case of attempted censorship and prosecution that no doubt had the effect, mentioned quietly by one participant in HBO’s documentary, of museums and curators censoring themselves pre-emptively.

In the context of the Culture Wars, which engulfed American society in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the uproar over photographs of sadomasochistic gay sex was unsurprising. At a time when raunchy rap lyrics were also being read aloud and condemned in Congress, the Mapplethorpe controversy offered yet more evidence of clashing values, generational conflict, and debates over conservative paternalism. But art has provoked outrage at virtually all times and in all places throughout recorded history; indeed, Mapplethorpe’s are not the only images currently on view at LACMA that have been the subject of controversy and censorship. A number of works in the exhibition The Seductive Line: Eroticism in Early Twentieth-Century Germany and Austria, which I organized for LACMA’s permanent collection galleries, were also provocative to the point of illegality, with even greater consequences for their makers.

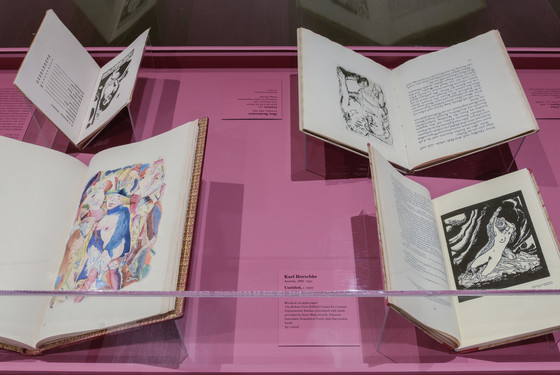

George Grosz, for example, found himself in trouble after the publication of his 1923 book Ecce Homo, which brings together 100 images that document the lurid street life of early Weimar-era Berlin. With the immediacy of a sketchbook, Grosz’s black-and-white lithographs present crudely rendered prostitutes, wounded soldiers, and bourgeoisie, all crammed into scenes that alternate between innocuous encounters in cafés and clandestine orgies. The addition of watercolor enlivens his drawings but invariably paints his figures as pallid, diseased, and dirty, with sex characterized as a source of delirious, dangerous pleasure. Objecting to the book’s graphic content, censors took Grosz to court on charges of immorality, resulting in the confiscation of copies of the book and heavy fines levied against both Grosz and his publisher, Wieland Herzfelde. Unfortunately, it was neither the first nor the last time that Grosz was persecuted for his work: in 1921 he had been accused of insulting the German army with his portfolio Gott mit uns (God with Us), a crime for which he eventually paid heavy fines; and in 1928 he was arrested and charged with blasphemy for irreverent, socially critical images that appeared in his portfolio Hintergrund (Background). Grosz’s repeated arrests have become part of the mythos of his prints, rendering them important not only as documents of Germany’s political struggles in the Weimar era, but also as artifacts of authoritarian rule and its repercussions for the cultural avant-garde.

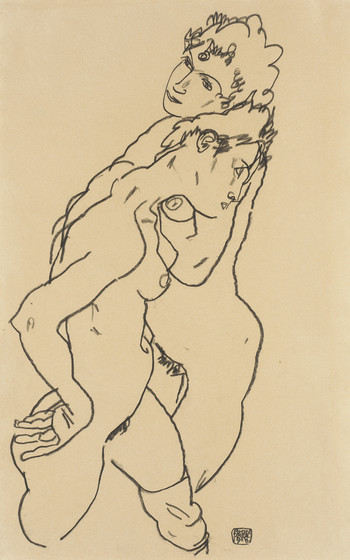

In Austria, Egon Schiele suffered similar persecution for his erotic work. Schiele’s oeuvre, which includes several thousand drawings, a handful of lithographs and etchings, and more than 300 oil paintings, is rife with images of the naked body—making it perhaps inevitable that he would draw the attention of censors. Schiele obsessively drew nudes from life, using the quavering, antic line of his pencil to invest even the most haphazard sketch or study with existential angst and longing. Young women, pregnant women, and heterosexual and homosexual couples numbered among his models, though he is perhaps best known for his many probing self-portraits, his near-emaciated, deformed body externalizing a tenuous subjectivity.

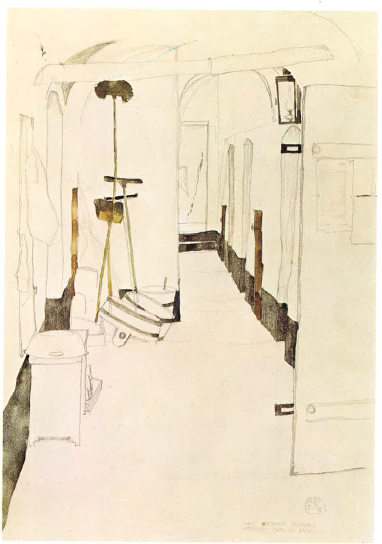

In a round-about way, however, it was Schiele’s use of underage models, a practice he shared with the artists of the Expressionist group Die Brücke, that upended his life, landing him in jail on immorality charges in 1912. The case originated in Neulengbach, a tiny village 20 miles from Vienna, where Schiele’s bohemian lifestyle had quickly rankled his conservative neighbors. A young girl infatuated with Schiele tried to run away from her parents to live in Schiele’s studio; the artist, who had a live-in mistress at the time, rejected the girl’s advances but agreed to allow her to stay at his home while she figured out how to reconcile with her parents. The girl’s father caught wind of her whereabouts and a police raid at Schiele’s home uncovered hundreds of drawings filled with provocative nudes. Charges related to the runaway girl were dropped when the court realized the misunderstanding that had occurred, but prosecutors saved face by continuing to argue that the drawings in the studio posed a threat to the morality of the children who visited as models. In the end, Schiele served 24 days in jail, paid a fine, and endured the humiliation of a judge publicly burning one of his drawings at trial. (If you’re interested in reading more about Schiele’s time in jail, I highly recommend Alessandra Comini’s 1973 book Schiele in Prison, which includes an English translation of his angst-filled diary entries.)

![Egon Schiele, Männlicher Akt (Selbstbildnis) (Male Nude [Self-Portrait]), 1912, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies](/sites/default/files/attachments/M82_288_383L-20151216.jpg)

Shortly after being released, Schiele made a series of self-portraits showing himself as a hermit and a monk, signaling a period of reclusion and social anxiety that would persist until his death from influenza just a few years later, in 1918, at the age of 28. Nearly a century has passed, and images that once appalled their straight-laced Austrian audience now hang nonchalantly on museum walls and above dorm-room beds; drawings once seen as ugly and vulgar are now largely perceived as strikingly poignant, even beautiful explorations of human fragility. Like Mapplethorpe and Grosz, Schiele is now firmly planted in the canon of Western art history, in part because mores and attitudes change over time, and what was considered inappropriate or lacking in aesthetic value in the past is judged differently today.

For many visitors to The Seductive Line, that point becomes most obvious when they confront excerpts of banned pornographic films from Vienna, which now hardly read as pornographic, especially when considered relative to Mapplethorpe’s photographs, or even some of the more explicit prints and drawings on view. I find that when artists push the bounds of what is deemed proper in their own time and place, they push potential viewers, present and future, to examine their own values and assumptions—exactly the kind of introspective reflection that museums, on their best of days, hope to foster.

Visit The Seductive Line: Eroticism in Early Twentieth-Century Germany and Austria before it closes on July 24.