Unframed is taking a look behind the scenes to profile the creative, dedicated people who make LACMA special. We sat down with curator Stephen Little to talk about how his science background informs his curatorial work, his fascination with copies and forgeries, and that precious moment when he realizes he doesn’t know something. Check back tomorrow for Part Two.

Tell us what you do at LACMA.

As a curator [and department head of Chinese and Korean art] I and my staff research and exhibit the permanent collection of both Chinese and Korean art. I devote a lot of energy into developing special exhibitions.

A lot of what we curators do is to take a work of art and try to reconstruct the world around it. Why did the artist choose those materials? What was the audience for a particular work of art? This involves a lot of research in disciplines outside of art history—language, architecture, literature, economic history, military history.

With the right questions in your interpretive material and your choice of objects, your audience will hopefully come out of an exhibition with an interest in something they might never have imagined they’d have. One can grab people’s attention with the sheer beauty of something. Once you have their attention, you can drop any number of concepts into the mix.

What special exhibitions are you working on now?

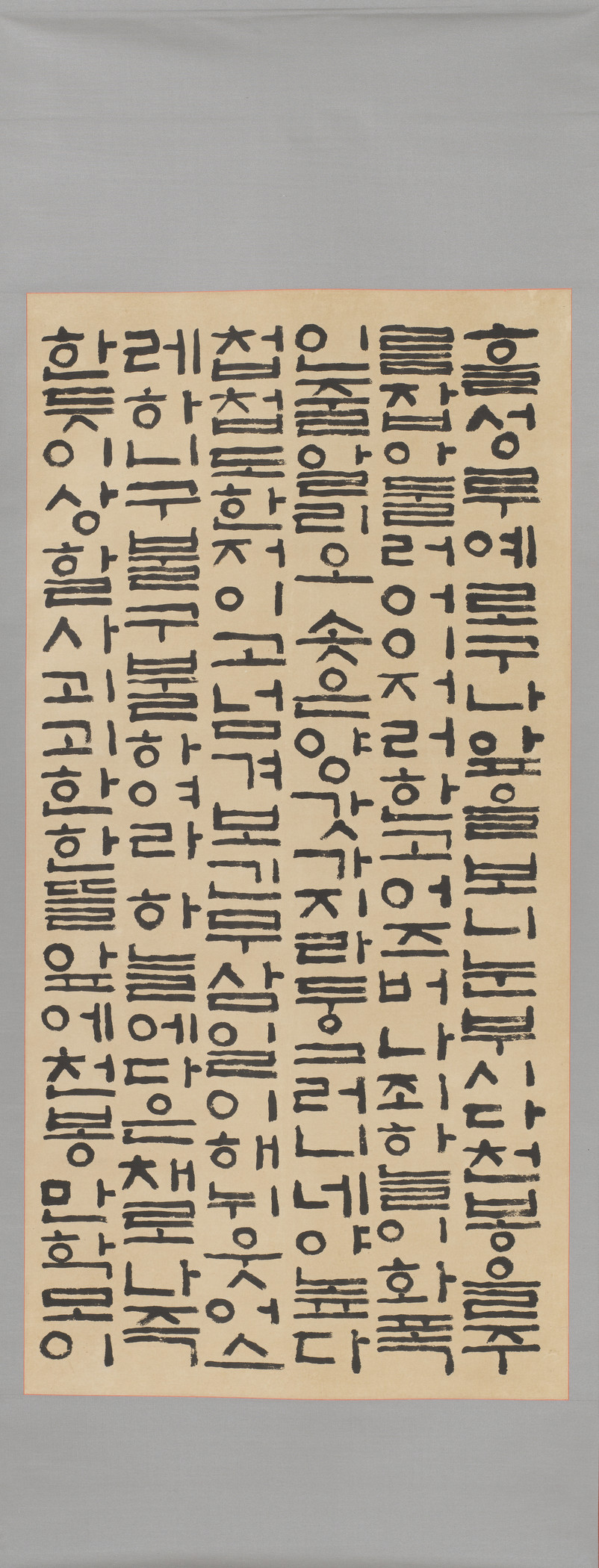

Right now, [associate curator] Virginia Moon and I are planning a big Korean calligraphy exhibition for 2019. This is the kind of show I get really excited about. It’s never been done before outside of Korea, certainly not on this scale. We’re looking at everything, from the earliest writing in the Three Kingdoms period to the first hangeul (the Korean phonetic writing system) typewriter, and focusing on works in both Chinese characters and hangeul. This show will be a window into Korean culture and Korea’s relationship with other countries.

Another show I’m really excited about is The Art of Qiu Ying, scheduled for the autumn of 2019. This Ming dynasty painter is deeply misunderstood—he painted in many different styles, and few of his works are dated. He’s also likely to be the most forged painter in Chinese history. There has never been a show about him outside of China or Taiwan. I’ve been working on this since 1978. Among the questions I’m asking is this: What does it mean to copy another painting in China? Copying could be a straightforward exercise as a primary way painters learned to paint, and it could also be the creation of something made to deceive. Among other things, I want to look at both aspects of this phenomenon, the history of forging in China, and some of the problems one encounters when studying Chinese painting.

Can you talk about those problems?

What happens when one encounters a painting that is genuine, but doesn’t resemble the artist’s other known works? That can be a problem—when scholarly consensus is against something but it just happens to fall outside of people’s experience of that artist. Qiu Ying was a painter who could do anything. He could paint in myriad different styles, and none of them look alike. To determine authenticity, it takes confidence in one’s own judgment, which one gets from looking at as many genuine and as many fakes as possible. I’m a student of fakes; I love copies and forgeries, and I’m interested in exploring the differences between the two concepts in this show. These are aspects of art making that are rarely explored in museum exhibitions.

With this show, we have a chance to present these issues of authenticity to the general public. The whole issue of plagiarism as problematic is a fairly recent idea. In Shakespeare’s time, copying was fairly common.

How do you tell the difference between a genuine and a fake painting?

The same issues occur in European painting. You might have a painter like Lucas Cranach, known to have done multiple versions of a painting, then his studio did several versions, and then his son does several more versions (and not all of them are signed). Where do you start? No matter what part of the world you’re dealing with, the questions of authenticity you ask of any work of art are basically the same. What is it made of? When was it made? Does it look like other things made in that time? Does it show its age? Does it reveal traces of wear and tear, or damage?

Anyone can ask these questions of any work of art. The minute you ask, you begin to understand something new. It seems mysterious and remote, but it’s not. We all know the difference between a Volkswagen and a Mercedes, because we’ve seen thousands of them. It’s essentially the same with Chinese painting; one just has to look, and ask the right questions. Of course, to do it well requires decades of learning and study, but the basic questions don’t change.

There are very few studies in English on how to distinguish a real from a fake Chinese painting. The most brilliant study of this subject was written in 1958—Chinese Pictorial Art as Viewed by the Connoisseur by Robert Hans Van Gulik, printed in Rome in a limited edition of 950 copies. This book is a discussion on traditional Chinese techniques of determining authenticity, of how one presents scrolls, and how they are conserved. In the back, the original edition has an appendix with samples of ancient silk and paper. Van Gulik actually took an 18th century Chinese painting, for example, and cut it up, and he also includes different Chinese papers that were used by painters, calligraphers, and book binders. To me, this book is a kind of Bible.

Did you know you wanted to be a curator when you were in school?

I really wanted to be an astronomer. I was an undergraduate at Cornell when Carl Sagan was head of the Center for Radiophysics and Space Research. I was working on the first discovered black hole in 1974 with a professor—not Sagan, he was far too exalted and didn’t talk to undergraduates. My downfall was calculus. I won’t even tell you the grades I got. I took an art history class in my sophomore year and immediately recognized that this was something I loved.

I then got a work-study job in the university museum at Cornell, which happens to have an excellent Asian art collection. I catalogued Chinese jades and ceramics. And that was it. I knew I had to work in a museum. I found the proximity to actual works of art so intellectually stimulating. You also really start to understand an object when you touch it, when you feel its weight and texture—that’s an entirely different level of knowledge from what one learns from books or slides.

How does your science background inform your work as a curator?

A physics professor told me two things that still influence me as an art historian and a curator. One day, he said, “Whatever I’m telling you today, be prepared to throw it out the window.” He meant we should be prepared to challenge our teachers—not that what he was teaching was wrong, but that it could always be refined and improved on.

The other thing he said was, “Don’t be afraid to ask big questions, to be ambitious in the questions you’re asking. But when you’re looking for the answer, look in the shadows, look in the places other people have forgotten to look.” When you try to answer a really big question, a cosmology question, you shouldn’t be afraid to look for the answer on the atomic level, because, as he said, in physics the structures of the macrocosm and the microcosm are similar—they’re not the same thing, but their structures are truly similar.

When I arrived in the world of art history, the history and ideas of art tended to be monolithic, especially in Asia. One was not encouraged to challenge one’s teachers. But I was encouraged in science to be subversive. In every museum I’ve worked at—and I’ve been lucky to work at many fantastic ones, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Honolulu Museum of Art—I started spending time in storerooms, looking for works of art that had been forgotten, overlooked, or marginalized in one way or another. Every museum has such works of art. I’ve discovered incredible, important, and beautiful things that had been sitting on a shelf for fifty years.

When you see something you’ve never seen before, you can either keep walking or you can stop and take it seriously for a minute. One of the most difficult things for a curator is to admit you don’t know something, that you’re truly ignorant about something. We put such stake in knowing. So when a curator who has years of experience sees something they’ve never seen, that’s the moment of truth. Are they going to keep walking, or are they going to stop and say, this is the moment I realize the depth of my ignorance? I love the challenge of that moment. That, to me, is what it’s all about.

Check out Stephen Little’s latest exhibition, Alternative Dreams: 17th-Century Chinese Paintings from the Tsao Family Collection, which is on view in the Resnick Pavilion through December 4.