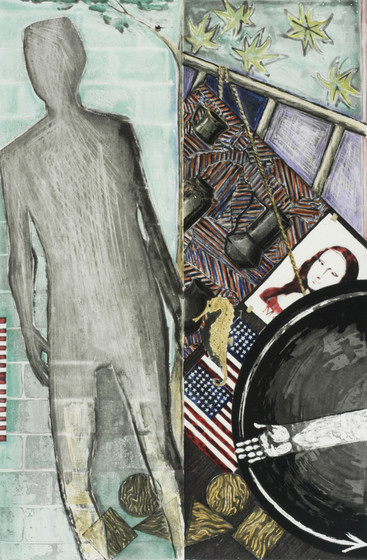

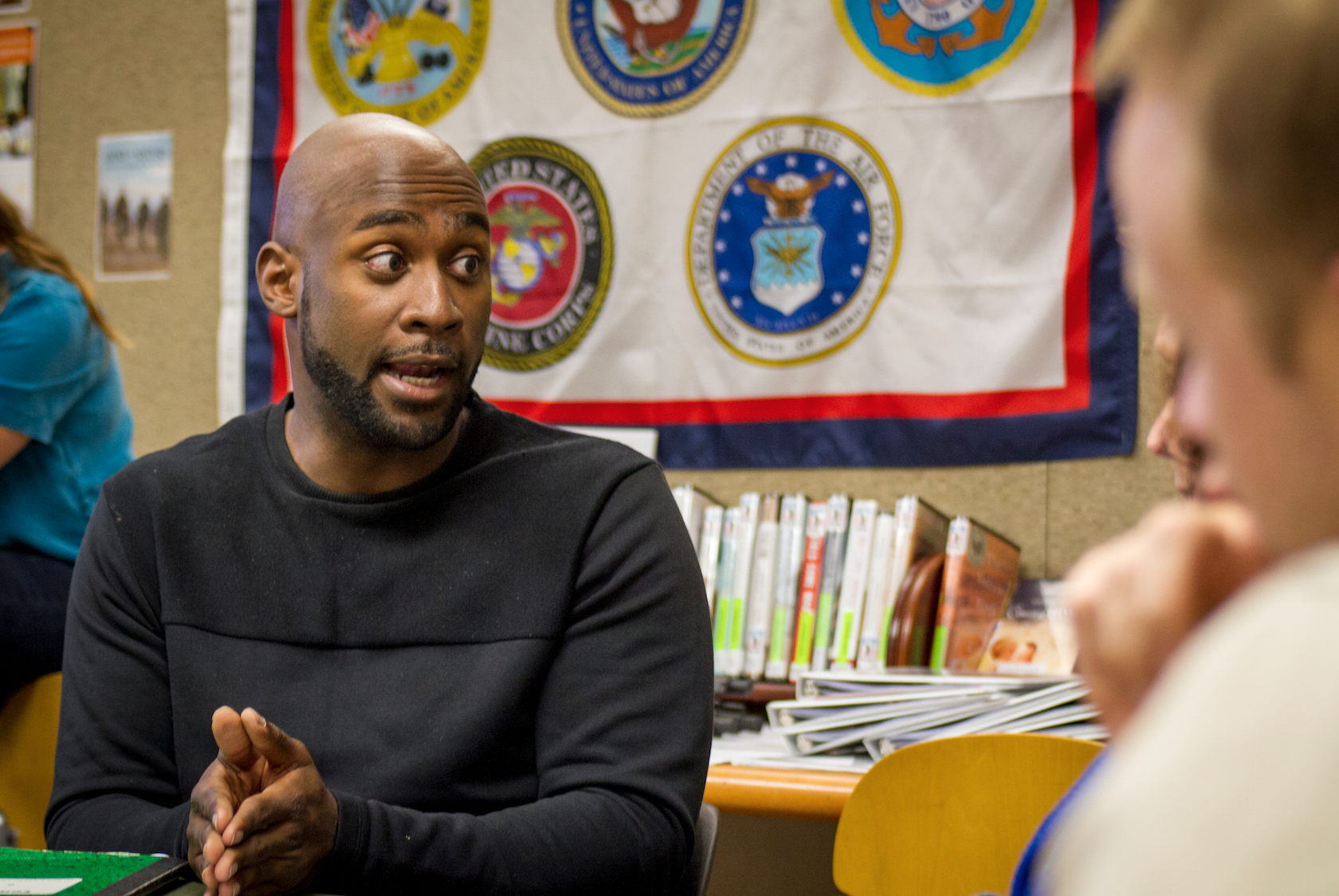

It’s Saturday afternoon in the Veterans Resource Center at Exposition Park Library, week two of LACMA’s pilot Veterans Make Movies(VMM) program. Launched with a federal grant, the three-year initiative teaches veterans how to tell their story in film and shares their films via screenings and an online archive. Sixteen participants in the inaugural class gather around a table in the darkened room, discussing fellow serviceman Jasper Johns’s The Seasons (Summer), which is projected onto a large screen. As the title hints, the print is part of a series that uses the four seasons as a symbol to reflect on the passage of time, life cycles, and, presumably, key moments from the artist’s own life.

At this point, though, the veterans are not aware of these details. During this initial phase of conversation, Hank Hughes, a veteran and one of the museum’s teaching artists for the program, is careful not to reveal any information about the artwork. This method frees participants from preconceived notions about the work. They can formulate questions and insights based purely on what they see, building on what their peers notice and drawing from their own experiences. There’s a good deal of ambiguity and symbolism in the print, making it well-suited for this approach.

After dissecting the imagery within the artwork for some time, a veteran muses, “I wonder how [the components in the painting] relate [to one another]. I know I’m supposed to understand something. It means something.”

Hughes asks the group to share interpretations based on their observations.

“It’s a journey into [military] service. It’s faceless. It could be anybody’s journey into service.”

“Maybe he’s leaving behind something. Maybe he came from war and that’s what he left behind.”

“It feels like time [for the figure depicted in the print] doesn’t matter anymore. That fog feeling you get from being in the military…I have that. Just kind of existing.”

Though brief, the exchange highlights the crux of the VMM initiative—art and film have tremendous capacity to communicate to the viewer. Without pre-existing knowledge or any obvious military references in the painting (other than, perhaps, the American flag), the veterans tapped into feelings associated with service and Johns’s own background in the armed forces.

Experiences as profound as serving our country no doubt color one’s point of view, but how? Civilians are generally not well versed in what it’s really like to go to war or the nuances of veterans’ coming-home stories. In some ways, this is to be expected, given that only one percent of the current population is enlisted. In contrast to the draft days when a higher ratio of men and women served, today’s all-volunteer force means that it can be quite common for a civilian not to personally know anyone active in the military. Due, in part, to this, sensationalist stories about post-traumatic stress disorder, homelessness, and substance abuse tend to get the most media attention. Without a multitude of other perspectives balancing out the narrative, the veteran experience can appear excessively negative, one-dimensional, and monolithic.

Just as there are countless motivations and factors behind why people enlist, there is not one archetype of who joins. Today’s military might be one of the most diverse institutions in the world. Satinder Kaur, LACMA’s teaching artist for the VMM program and former preventive medicine specialist for the U.S. Army in Baghdad, relays: “I moved to this country when I was 11. Because I’m an immigrant and a woman, I’ve been told innumerable times that I do not ‘look like’ a veteran.”

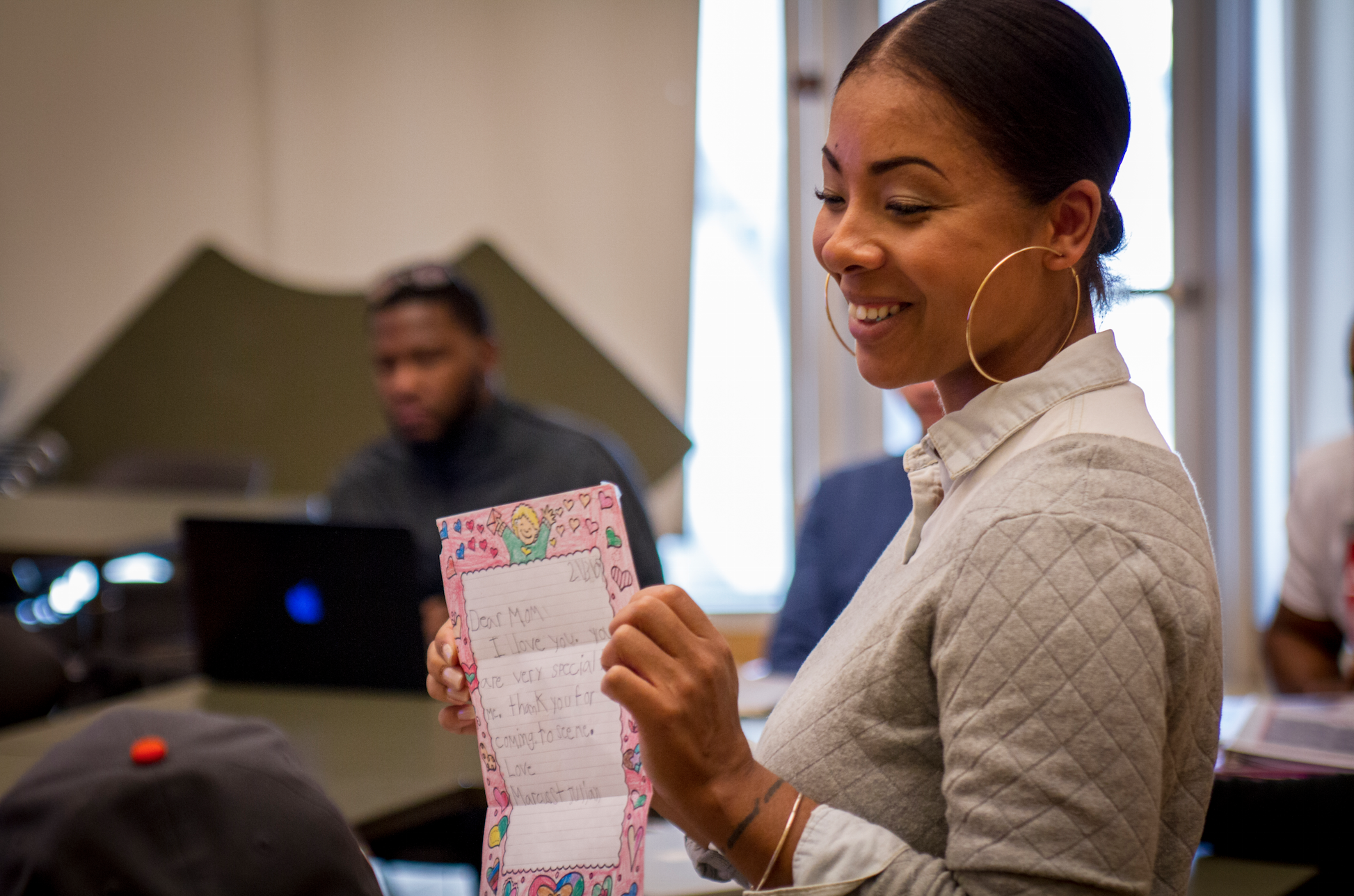

Similarly, the veteran experience is far from universal. While many service members face varied physical and mental health conditions and find that readjusting to home life, reconnecting with family, finding work, or going to school is an ongoing struggle, others return relatively unscathed. Most often, veterans fall within a gray area between two ends of the spectrum and report having conflicted feelings about their time in the military. It’s possible that they are unsure of how to process their extraordinary experiences or characterize it to themselves, much less to a non-veteran.

Irresolution, tension, complexity, ambiguity—this is a kind of “sweet spot” for art and film. The open-ended nature of The Seasons is precisely what enabled the veterans to personally connect to it. The power of the art- and film-making processes to spur its creator to examine unresolved feelings is something that LACMA teaching artist Hughes understands firsthand. The Oscar-nominated filmmaker and former paratrooper explains, “For me, life at war was hyperbolic. After entering a fight-or-flight mode a few times, your perspective changes as much as your physiology. There is a sublime quality that permeates my memories that cannot reconcile the beautiful and the awful. It’s hard to describe, and this breakdown in language calls for creative expression.”

Kaur also recognizes the value of the creative process in making sense of the otherwise inconceivable: “Creativity arises from desperation; that aching need to find a means through which to express something that moved us, inspired us, or even frightened us. The veteran experience is unique in that we have been forced to confront our morality because we’ve been in places where we had little to no security. Experiences like that set you on a path to wrestle with the meaning of things and purpose in it all, and that wrestling manifests itself in the creative expression.”

Hughes, Kaur, and the other LACMA teaching artists, Shawn Spitler, Brigid McCaffrey, and Tuni Chatterji, help the veterans transition from viewers to makers of their own short films. They learn the technical aspects of filmmaking: how to write, shoot, and edit. But most importantly, they learn how to hone their point of view and exploit the capacity of the medium to communicate, even if the message isn’t always clear-cut.

One participant uses film to explore the guilt he feels for having never experienced combat by asking, “What makes a veteran?” Another veteran wrestles with the uniform as a symbol of what is both lost and gained when individual identities morph into a collective body. One film is told from the perspective of the veteran’s unborn child, while another is expressed by a Vietnam War-era veteran who served in the all-female branch of the Army at a time when women were not allowed on the front line. The diverse content of the films reflects the heterogeneity of the veteran community.

The films produced in the VMM program create a richer, more nuanced view of the veteran experience. There is potential for these films to lessen the gulf between veterans and the remaining 99 percent of the population, which often include family and friends who struggle to relate. This is the power of art and film for both the maker and viewer, and the essence of LACMA’s VMM initiative.

A selection of these veteran-made films will screen at LACMA on Sunday, October 30, to celebrate Veterans in the Arts and Humanities Day. Following the screening, Norman Lear, World War II veteran and revolutionary television writer, producer, and director, will discuss his latest projects.

Are you a veteran interested in participating in the winter session of the VMM program? Apply on our website through December 2.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Sony Pictures Entertainment, and The Albertsons Companies Foundation and The Vons Foundation.