In March 1976, two months after starting work at LACMA, I read the Los Angeles Times obituary of John McLaughlin, an artist whose work had been unfamiliar to me before I moved from New York to L.A. My interest had been piqued by a recent acquisition, McLaughlin’s #5 (1974), which was then hanging in the modern galleries at the museum. I was drawn to the startlingly simple white canvas with two parallel black rectangles, and I wanted to know more about the artist and his work. As I began to visit studios around town, several artists were quick to tell me what a remarkable painter he was and how important his work was. While preparing a show of six of Ed Moses’s new red abstractions for that summer, I listened as Moses spoke eloquently about McLaughlin, calling him one of his heroes of abstract painting. James Hayward and John M. Miller, with whom I was in discussions for a small show of four L.A. nonobjective painters at LACMA in 1976, both said McLaughlin’s example was critical to them as well; they spoke with reverence for his reductivist painting on a human scale and for his resolute approach, which managed to captivate the mind without relying on metaphor. Tony Berlant, Joe Goode, and Robert Irwin also spoke with conviction about the significance of McLaughlin’s work.

So it was not surprising that, a few months later, McLaughlin would be one of the artists my colleague Maurice Tuchman and I sought to feature as we conceived of a series of one-room historical exhibitions grouped together under the title California: Five Footnotes to Modern Art History, which would coincide with the 1977 meeting in Los Angeles of the College Art Association. We chose to revisit the seminal 1959 Los Angeles County Museum exhibition Four Abstract Classicists, curated by Jules Langsner, which had presented the Hard-Edge paintings of McLaughlin, along with those of Karl Benjamin, Lorser Feitelson, and Frederick Hammersley. Two of our mini-shows—Los Angeles Hard-Edge: The Fifties and the Seventies and John McLaughlin: Letters and Documents—introduced him to a national group of art historians and served as a memorial for an L.A. audience that so esteemed him.

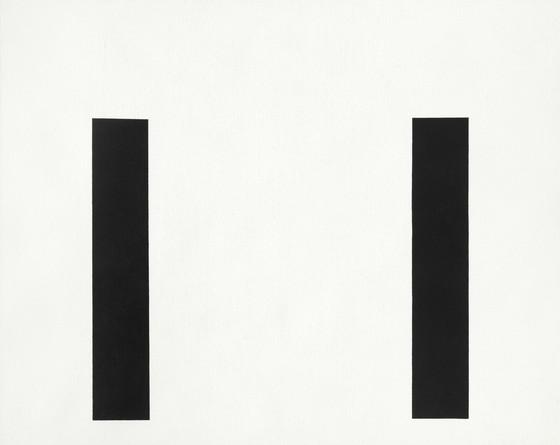

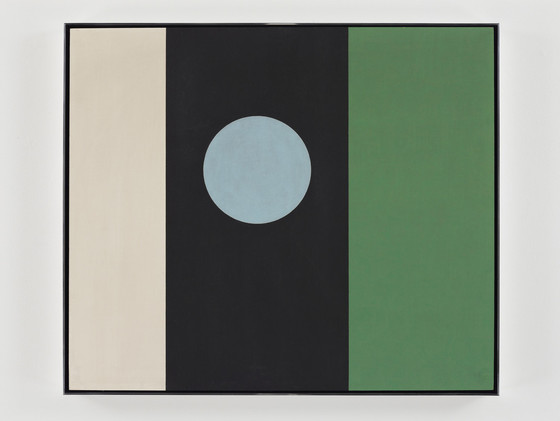

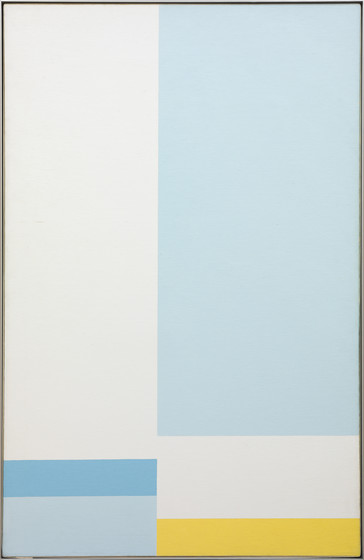

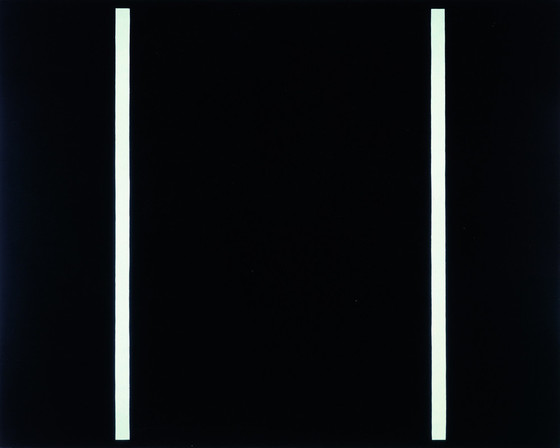

With only casein or oil paint on canvas or Masonite, McLaughlin constructed intimately scaled paintings that defied traditional notions of perspective, depth, and dimensionality. Compositionally, his canvases usually have equal numbers of rectangular bars on the left and right sides, or they are constructed horizontally with wide bars that cut across the full width of the picture plane. The spaces between the bars—the “empty” spaces—seem to take on a weight equal to the painted rectangles, upending conventional designations of foreground and background. Our eyes are repeatedly drawn to the vacant space. This “perceptual void,” as Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight has described it, was something that McLaughlin admired in the scroll paintings of Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506), which sought to draw the viewer into the space of the picture.

Born in Massachusetts in the last years of the nineteenth century, McLaughlin was a self-educated artist who never went to college. He was well read, had a deep knowledge of Japanese and Chinese art, and explored literature, aesthetics, philosophy, and Eastern spiritual texts on his own, in addition to keeping up with art magazines. He only began painting serious abstract works when he was in his late forties and pursued an art practice while living in two small seaside towns south of Los Angeles, where he and his wife had settled following World War II. He remained mostly isolated for his thirty years as an artist and was never part of the L.A. contemporary art scene that emerged around the Chouinard Art Institute, which closed in 1961 (later reopening as CalArts); the Ferus Gallery, which operated from 1957 to 1966; or the Dwan Gallery, which was active in Los Angeles from 1959 to 1967. McLaughlin died in 1976 at age seventy-seven, just as his paintings were beginning to gain wider recognition.

McLaughlin’s reputation seems to have languished after his death, perhaps partially the result of his living and working outside the mainstream L.A. art world. Although his work was included as part of the Four Abstract Classicists show in 1959, McLaughlin never really fit neatly into any group of artists. Unlike many prominent L.A. artists, he did not teach at any of the area art schools and had infrequent contact with fellow artists. In the 1950s the two leading painters of his generation in Los Angeles were figurative artist Rico Lebrun (1900–1964), who taught at the Chouinard Art Institute, and abstract painter Stanton Macdonald-Wright (1880–1973), who taught at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). McLaughlin was a generation older than two of the three other artists who were part of the 1959 show Four Abstract Classicists —Fred Hammersley (1919–2009), who studied with Lebrun, and Karl Benjamin (1925–2012), who taught at Pomona College and Claremont Graduate School—but he was an exact contemporary of Lorser Feitelson (1898–1978), who was instrumental in the organization of the show.

In the 1950s and 60s, artists like expressionist-style painters Lebrun and Howard Warshaw and Ferus Gallery artists such as Ed Kienholz, Ed Ruscha, Billy Al Bengston, Ken Price, Ed Moses, Wallace Berman, Larry Bell, and Irwin exhibited frequently. McLaughlin, in contrast, exhibited regularly at the Felix Landau Gallery beginning in 1952 but was the lone resolutely abstract painter in Landau’s program, which was aligned more with European artists Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, and Henry Moore and with more figurative California artists like Richard Diebenkorn, Jack Zajac, Paul Wonner, and James Gill. Unlike Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and Kazimir Malevich, McLaughlin did not begin with naturalistic imagery that he progressively reduced to abstraction; rather he began as a full-fledged nonobjective painter. His resolutely abstract paintings were marginalized in the familiar story of L.A. painting in the 1960s, eclipsed by young artists working with new and experimental materials, creating assemblages from detritus, and using Pop imagery.

Although he had no formal training, he had a lifelong interest in and was deeply knowledgeable about Chinese and Japanese art, particularly Japanese prints of the fourteenth through sixteenth century, which he both collected and sold. He most particularly admired the work of the Zen monk-painter Sesshū, whose austere black-and-white landscapes with large expanses of white were familiar to McLaughlin from his boyhood in Massachusetts, when he saw them at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He traveled not to the familiar European cultural destinations of Greece, Rome, Florence, Paris, and London but instead spent two years during his thirties touring Japan and China with his wife, continuing his study of Japanese and assembling a collection of Japanese artworks, many of which he sold to support the couple.

While it might be tempting to locate McLaughlin’s paintings within a European Constructivist tradition, his work does not follow in the history of early twentieth-century abstraction, which itself was rooted in nineteenth-century landscape painting by way of Cubism and a distinct application of perspective. Although works by Ad Reinhardt and Barnett Newman may share some visual similarities, they come from a different source, reducing experiences to essential forms. McLaughlin, by contrast, avoids any form that might suggest experience, emotion, or anything recognizable. McLaughlin was drawn to the abstract paintings of Mondrian and Malevich but he likely never saw the works in person; his familiarity was based instead on reproductions. (No museum in Los Angeles or Boston, where he grew up in the suburb of Sharon, had work by either artist on view during the 1950s.)

At a time when the large, bold, gestural, colorful paintings of the Abstract Expressionists were the focus of critical attention, McLaughlin’s spare, clean, easel-size abstractions—composed mostly of rectangular shapes with smooth, uninflected surfaces and crisply defined edges—stood in sharp contrast. Similarly, his palette of black, white, and gray, offset occasionally by pale blues and soft greens, along with striking yellows and reds, differed from that of his peers. His works are resolutely two-dimensional; they express no content. Although they may appear simple, these paintings richly repay concentrated looking; the issue of meaning is left open-ended, to be completed by the viewer. As such, they could be considered precursors to the work of artists including Irwin, James Turrell, and Doug Wheeler, who were associated with the Light and Space movement.

McLaughlin wrote often of the demands that his work places upon the spectator: “The painting is not intended to be understood in the sense that the regard is in figuring out what it ‘means.’ On the contrary, the acceptance is in participating in the act of coming to grips with reality.” These essentially phenomenological concerns were shared by the Light and Space artists, whose works are conceived to be completed by the presence of the viewer and often require significant time to appreciate. That experience cannot be rushed, as it takes time for the retina to adjust to adequately see the artwork.

In the forty years since McLaughlin’s death, he has remained something of an “artist’s artist,” held in high esteem by a coterie of artists, critics, collectors, and curators but otherwise virtually unknown. He arguably ranks as the first great artist to emerge in Southern California after the war, and his modest, rigorous, and tough abstract paintings are poised to be appreciated by new audiences.

This essay is excerpted from the exhibition catalogue for John McLaughlin Paintings: Total Abstraction, which is on view in BCAM through April 16, 2017.