For many viewers the subject of most Indian paintings is understandable even without a specialist’s knowledge of the identity and history of the figures portrayed. For example, images of a princely couple listening to music on a palace terrace can be appreciated without needing to know the historical or literary identity of the protagonists. Beyond this basic intelligibility, however, many works feature complex subject matter, symbolic nuances, and/or compositional substructures that require an in-depth explanation to understand their layers of meaning.

Allegories

Inspired by the iconography and mythology of Western divinity and sovereignty featured in the European prints brought to India, the Mughals and other Islamic dynasties of India soon appropriated the visual attributes of the divine and the regal for their own glorification. Chief among these emulated personages were Solomon and David, kings of ancient Israel; Orpheus and the philosopher Plato, both legendary musicians and poets of ancient Greece; and Majnun, the famous Arabic poet and unconsummated paramour of his beloved Layla. The unifying thread in the stories of these influential personalities was that each was graced with the ability to tame and control animals by means of his musical ability and/or spiritual authority.

Perhaps the most important Mughal allegorical images are a series of portraits of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605-1627). During his later years, characterized by political turbulence, regional famine, and his protracted poor health, Jahangir was inspired by a self-exalting dream to commission these allegorical portraits in order to extol his righteousness and imperial supremacy. The dream portrait in the exhibition, Emperor Jahangir Triumphing Over Poverty, has an inscription that explains the Emperor's symbolic act of shooting arrows at an emaciated old man emblematic of poverty. The chain stretching from heaven to earth represents God's justice manifested in Jahangir, and would have been a recognizable allusion to the golden "chain of justice" hanging from a tower in the imperial palace at the Agra Fort that had been installed for citizens wanting to appeal to the Emperor.

Metaphors

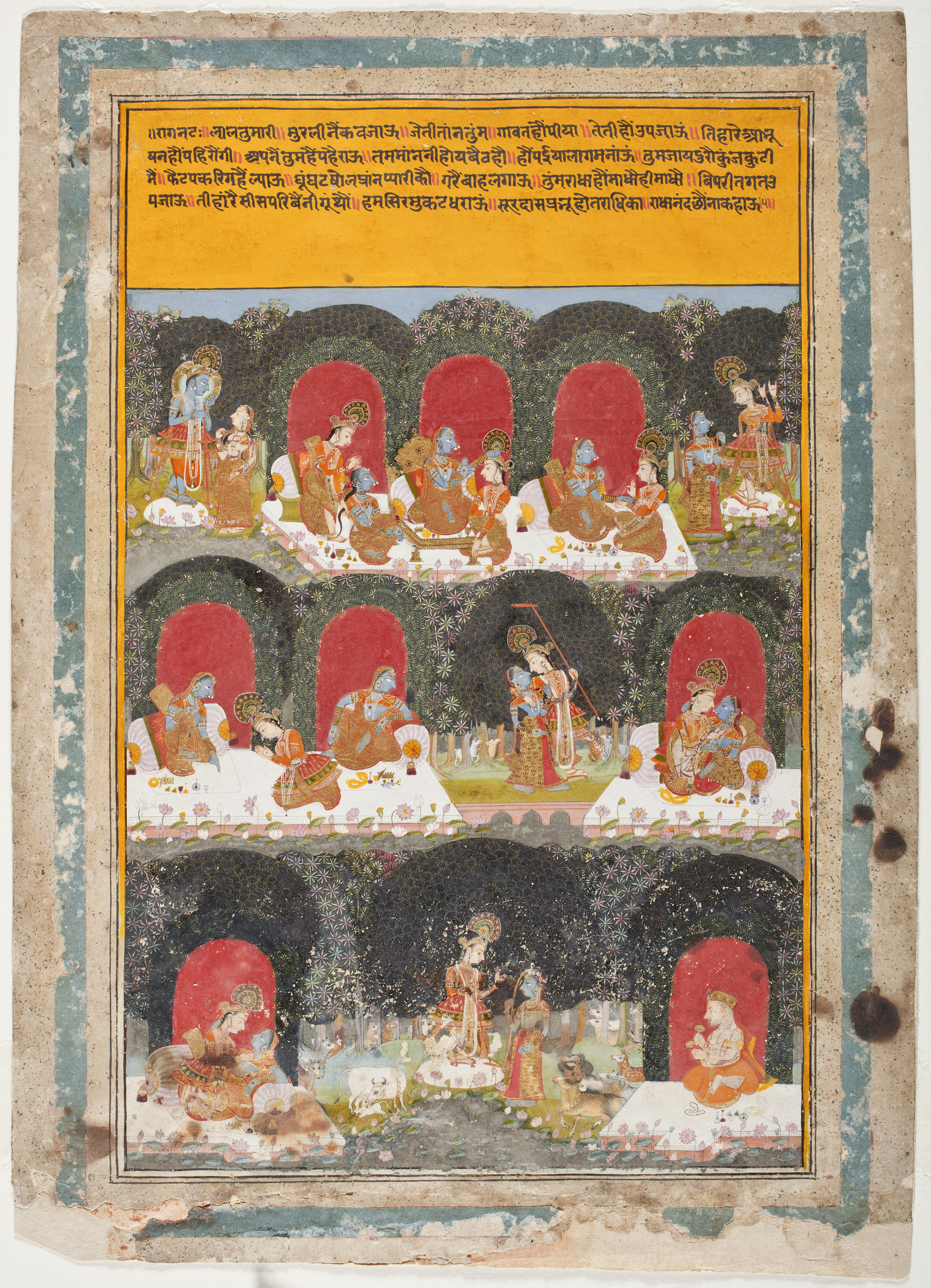

The use of visual metaphors in Indian art was especially prevalent in images associated with Vaishnava Bhaktism, a form of worship focusing on the Hindu avatars Krishna and Rama that was popular in northern India during the 14th–17th centuries. Numerous poems and prose expressed the core belief of the Bhakti movement that a devotee's loving adoration for one's personal deity was a metaphor for the ultimate union with a transcendent god.

The Reversal of Roles, Episodes from the Krishna Lila (The Play of Krishna)'s three registers of multiple images of Radha and Krishna wearing each other's clothes and grooming each other in role-reversal scenarios brilliantly express the intrinsic identification of the worshiper and the worshiped as theorized in Vaishnava Bhaktism. The painting's inscribed poem is drawn from the enormous corpus of devotional poetry ascribed to the preeminent Hindi poet Sur Das (1478-1573) and his followers. This is one of three best-known paintings from this series. Intriguingly, in each painting the blind poet Sur Das is shown seated and singing his verses to the accompaniment of golden hand cymbals.

Outlanders and Caricatures

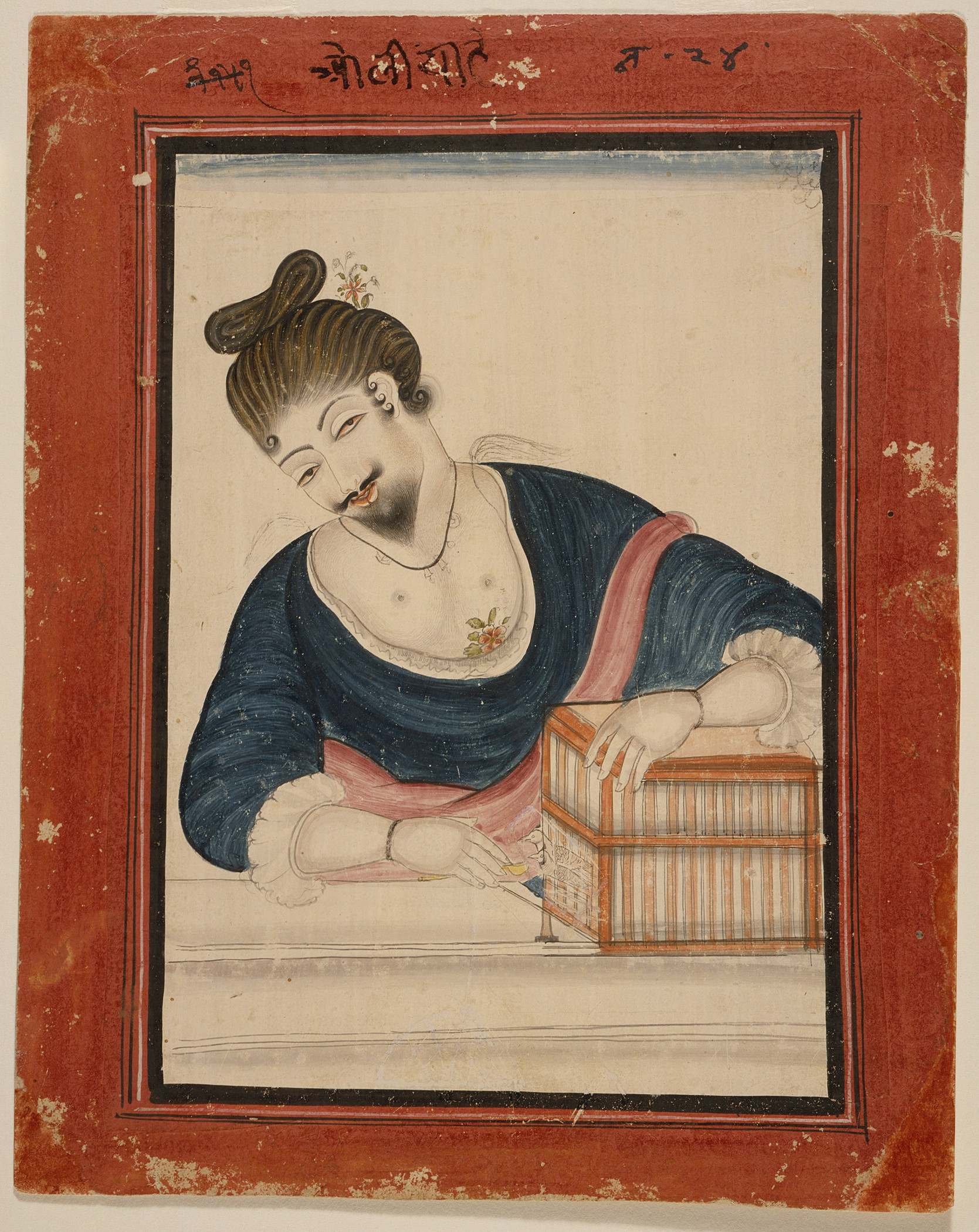

Since the earliest periods of South Asian art, exotic foreigners and otherworldly anthropomorphized creatures have been often depicted as caricatures with exaggerated features and convoluted postures, and frequently wearing misunderstood foreign or hybrid garb. In Indian paintings of the later 16th through 19th centuries, there was a renewed interest in portraying bizarre-looking outlanders, as well as comical Indians. Based primarily on the distinctive figural forms found in European prints and engravings circulating in India during the time, and from personal observation of the many European merchants, travelers, and political and religious emissaries that were increasingly commonplace throughout India, painters took evident delight in depicting such literally "outlandish" characters, often as stereotypes and stock motifs. These seemingly humorous or satirical observations of the “Other” could be termed Occidentalism, an Asian corollary of Orientalism, the artistic vogue in 19th-century Western painting for romantic images expressing the exoticism and allure of Middle Eastern culture. Among the most popular of these Occidentalist subjects were the foppish “Farangis” or Franks, a name used generically and often disparagingly to refer to the French, Portuguese, Dutch, and English alike.

Bestowed with a topknot, mustache, and goatee, the figure in European Fortune Teller Feeding Pet Birds wears a loose shawl over a shirt with a lace collar and folded cuffs, both features inconsistent with Indian fashion. The fortune tellers’ birds would pick a playing card to tell the customer’s future or fortune, thus making his occupation seem equally bizarre to his audience.

A peculiar subset of the farangi genre features a pair of grinning buffoons. The visual source of these enigmatic expressive figures was apparently the representation of fools in 16th- and 17th-century European paintings and prints that illustrated the Dutch proverb, “the world feeds many fools.” The figures’ gesticulation of touching their nose with their forefinger has been said to suggest the use of snuff, but the gesture may have also found resonance in the Indian cultural context from its resemblance to the well-known hand position expressing astonishment where the index finger and sometimes the middle finger are held touching the chin or lips.

Subtleties, Complexities, and Obscurities

Sometimes subtle nuances of the painting can confirm the identification of the subject. Dedicatory inscriptions often convey the underlying rationale for an enigmatic work, but works with multiple, esoteric, effaced, intrusive, and/or incorrect inscriptions make the interpretation far more complex, especially when variant translations are rendered. Even more perplexing are works with pseudo-inscriptions, which cannot be translated, such as those on an ivory manuscript cover. Images with obscure or atypical subject matter are also confounding, insofar as it is difficult to determine relevant comparisons or related works from the same series. To muddy the waters even further, these various categories of obliqueness can also be combined in a single work, such as when earlier images are reworked in a pastiche, which renders a new composition that can be both complex and obscure.

An example of obscure and grisly imagery, this double-sided folio of A Demon with Two Chained Men (recto), Man Bitten on the Arm by a Tiger (verso) is likely from a Jain karma series depicting the punishments in hell of evil doers. The Jain pictorial tradition of such hell scenes of torment and torture includes murals, manuscript folios, and the better-known large-scale representations on cloth of the cosmic man (loka-purusha) whose compartmentalized body symbolizes Jain cosmographic views of the structure and nature of the universe.

The didactic inscriptions on this work, albeit somewhat cryptic and inexact per the painted imagery, have been translated as follows:

Recto (Demon with enchained souls)

Do auspicious Dharma, occasionally would be hit.

Later does bad deeds, thus get hit.

Observe Dharma.

To get result of it

Do Karma, offer Daan [offerings] to God and reduce sins.

Verso (Tiger biting arm)

Follows wrong path, head would be striked.

Observe religion and Karma.

Deciphering enigmatic images successfully often depends on a combined approach involving the close examination of the work's features, an understanding of its historical milieu, a full reading of the inscriptions and determination of their viability, and, if available, a scientific analysis of the materials and methods used by the artist. These works of art and many more on view in The Enigmatic Image: Curious Subjects in Indian Art in the Ahmanson Building. Visit the exhibition before it closes on March 12 to take a closer look.

This post is excerpted from a longer essay on asianart.com and lightly edited.