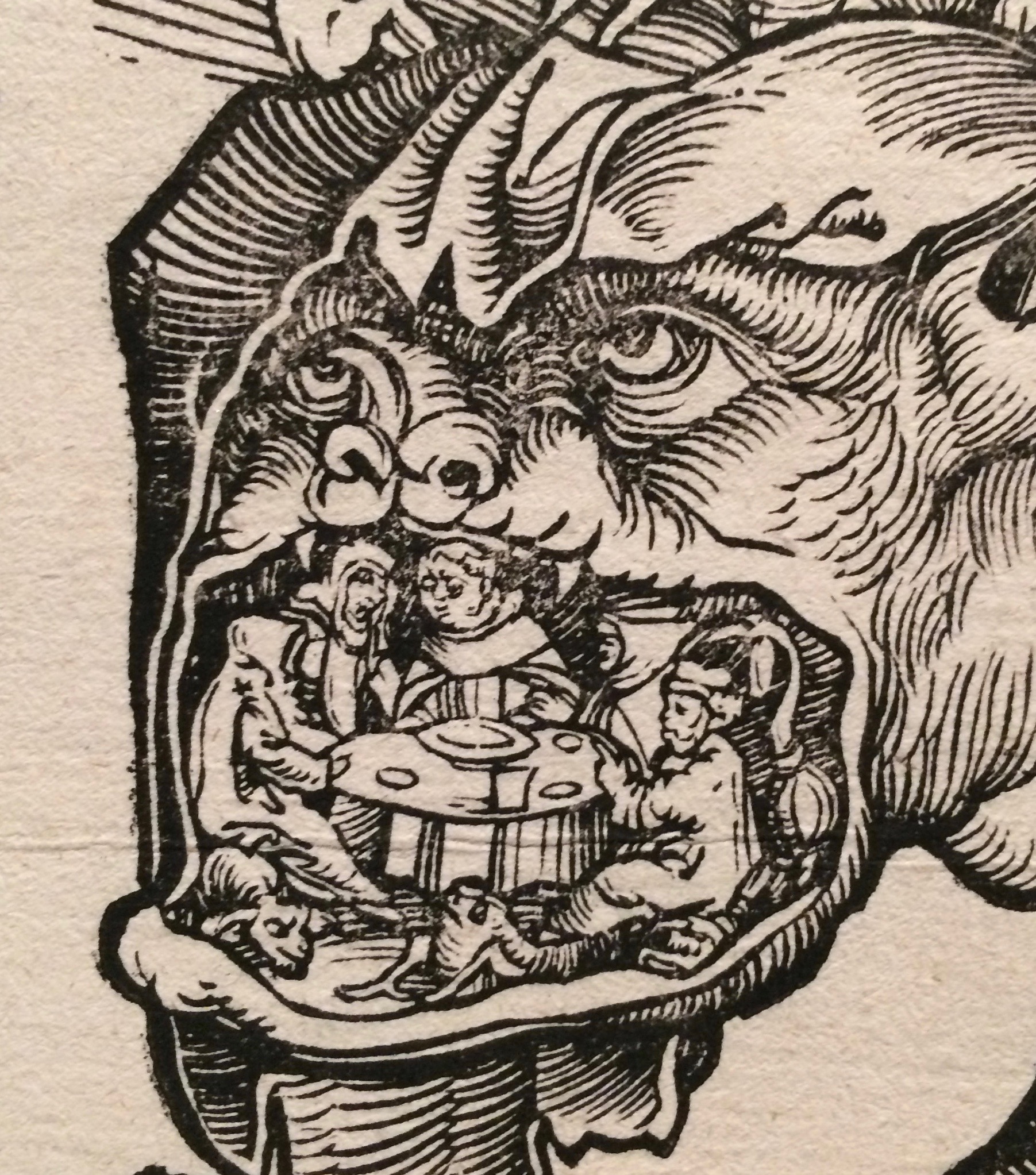

I had seen this image a thousand times without knowing who had made it and only the vaguest idea of its origins. I had seen it in textbooks, lectures, and in the form of countless JPEGS floating around the internet. So when I got to see it up close in LACMA’s exhibition Renaissance and Reformation: German Art in the Age of Dürer and Cranach, you could imagine my sense of déjà vu.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised. The Protestant Reformation, historians often tell us, was the world’s first modern media event. Without the incredible deluge of printed propaganda spreading the gospel of Martin Luther, the movement would never have had the impact that it did. After all, Luther wasn’t the first to complain about the corruption of the Catholic Church, nor the first to call for the Bible’s translation into the common tongue. (John Wycliffe tried during the 14th century. Jan Hus tried during the 15th. Neither attracted a fraction of the following that Luther did.)

But the fact that more content was churned out of German-speaking cities and towns doesn’t explain the media’s real significance to the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther put a premium on the written word—reading the Bible for oneself was one of his most radical and important teachings—but the objects through which his ideas were transmitted spoke just as loudly as the messages.

The printing press had been around for about 70 years by the time that Luther posted his 95 Theses on a Wittenberg church door. Pre-1517 publications, however, were poorly equipped to spread ideas quickly. For the most part these books were long and expensive tomes written in Latin, directed at a tiny scholarly audience. Reformation printers changed all of that. First, they unleashed a flurry of cheaper, shorter, German-language volumes, putting books into the hands of millions of people who had never owned them before. Nor were these even “books” in the traditional, leather-bound sense of the word. The 16th century was the golden age of the unbound pamphlet or “quarto folio”; in other words, a sheet or two of paper folded into four or eight smaller pages. Thin, cheap, and easily stuffed into a shoe or a coat pocket, folios were designed to go viral. Pettegree argues that German printing presses churned out over 7,000 editions of new pamphlets between 1520 and 1525, more than double the number from the entire decade before.

None of this would have happened without an artist’s help. As historian Andrew Pettegree has pointed out in his recent book, Brand Luther (2015), the new publications’ design was one of the Reformation’s most critical yet understudied legacies. For this we have Luther’s artist friend, Lucas Cranach the Younger, to thank. Cranach ensured that Reformation publications were visually distinctive, with elegant title pages framed by intricate allegorical woodcuts of his design, and an unmistakable “made in Wittenberg” stamp. (It was a once-in-a-lifetime partnership, with Cranach playing Jobs to Luther’s Wozniak.)

Pamphlets weren’t the only kind of new media that benefitted from an artist’s touch. Broadsides, woodcuts printed on only one side of a sheet of paper, were the cheapest and most shareable news form of all. Visceral, shocking, and illustrated in incredible naturalistic detail, broadsides resonated powerfully in a society where only a fraction of the population could read, even in the wealthy cities and university towns. And given the broadside’s penchant for symbols and stories already percolating through popular culture (fairies, demons, legends of miracles and monstrous births) it’s hard to ignore their likeness to the memes and rumors that saturate today’s media landscape. Indeed, Gerung’s woodcut is a powerful image of an enduring 16th century conspiracy theory. It strips away the arcane trappings of ritual and tradition, exposing the Catholic church, Protestant reformers believed, as the rapacious monster that it really is.

Luther was a complicated and contradictory figure, and as long as the political winds continue to change, historians will continue to reevaluate his legacy. In this light, it feels particularly fitting to look more closely at his impact on modern media culture. Luther died long before the first newspaper saw the light of day. Yet by finding new ways to fuse art and design with the emergent technology of print, the Protestant Reformation created an audience and appetite for information that was, in Pettegree’s opinion, “every bit as dramatic as the fundamental questions of theology his movement posed.” Renaissance and Reformation: German Art in the Age of Dürer and Cranach reaffirms the power of art—whether created in support of the status quo or in resistance to it—to both inform and disseminate the messages that we create.

Renaissance and Reformation: German Art in the Age of Dürer and Cranach is on view at LACMA through March 26.

For further reading:

Andrew Pettegree, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation. New York, Penguin Press, 2015.

Robert Scribner, For the Sake of Simple Folk: Popular Propaganda for the German Reformation. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.