For the past 25 years Frances Stark (b. 1967) has been making and exhibiting work in painting, collage, photography, time-based media, books, and other art forms. Widely respected in Los Angeles as a professor and a mentor, she has collaborated with a remarkable range of individuals including writers, dropouts, virtual partners in online video platforms, and, more recently, Bobby Jesus on the seminal video installation Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater B/W Reading the Book of David And/Or Paying Attention is Free (2015). Her recent works demonstrate novel ways of storytelling, with sexual overtones, poetic verve, and comic timing. My Best Thing (2011), for example, a film which premiered at the 54th Venice Biennale, derives from transcripts of her exchanges with partners online. In these works, Stark’s unusual approach to lyricism and her signature economy of means are employed in full force. Her unique balance of light-hearted jest and philosophical inquiry ventures into the bawdy while remaining elegant, often probing prickly issues of race, class, and gender with joyous and agonizing sincerity.

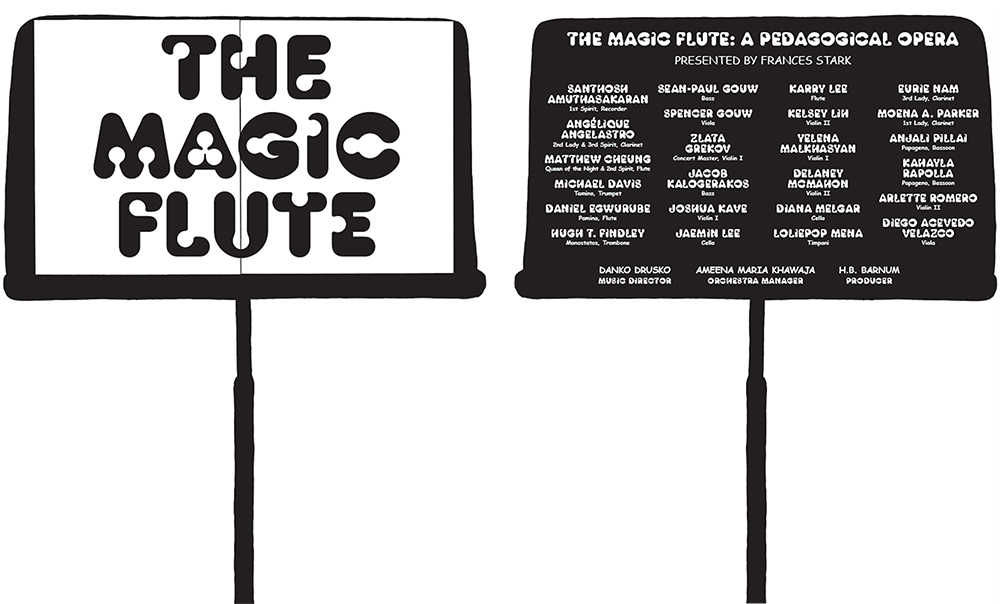

Premiering at LACMA on Friday, April 28, Stark’s newest work, The Magic Flute (2017), is an approximately 110-minute film adaptation of the popular 1791 opera by composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and librettist Emanuel Schikaneder about a prince and a bird catcher who cross paths and endure various tricks and trials in search of love. For the project Stark collaborated with a set of people from disparate parts of the music world. Conductor Danko Drusko, a PhD student at the time of the production, adapted the entirety of Mozart’s score. The revised version removes the vocal element, allowing for all songs besides the overture to be played by a 13-person string plus timpani section, accompanied by solo instrumentalists playing the melodies originally composed for singers. He also oversaw each rehearsal and conducted the players during each recording session. The legendary producer and arranger H.B. Barnum recorded and mixed the music; cellist and mezzo-soprano instructor Ameena Maria Khawaja organized the audition and the student players throughout the entire process; and percussionist and film composer Greg Ellis added rhythmic effects and finalized the soundtrack. The music in the film is performed by a group of young musicians (ages 10 to 19 years old) who auditioned for the project and came together to form a string section orchestra and a collection of solo instrumentalists. Stark’s adaptation of The Magic Flute confronts notions of power, cultural capital, and institutions (i.e. the museum, the university, the opera) with an invitation to a more humanized experience of beauty, kinship, and art.

Stark says of the film: “I’m trying to make The Magic Flute unfold for people very directly and joyously; it isn’t about clever redressing or anything, it’s really about the bare bones of the opera having the capacity to engage you, the original accessibility of the opera was based on its high-low conceit.”

Stark began working on The Magic Flute following the opening of her critically praised mid-career survey UH-OH: Frances Stark 1991–2015 (2015–16) at the Hammer Museum and receiving the 2015 Absolut Art Award. It also developed in the wake of a highly publicized controversy at USC’s Roski School of Art and Design where she had been tenured professor. Stark resigned from her position several months prior to the very public withdrawal of the entire class of MFA students amid administrative changes that she felt “flaunted an egregious disregard for the fundamental human endeavor we cherish as Art.” She remarked, “I believe what is at stake here is not confined to the academy but involves the entire fractured cultural landscape of Los Angeles, the fragile role of the individual artist, and the un-commodifiable human voice itself.” Perpetually invested in speaking to socio-political concerns through the lens of the personal and via her art, it is no surprise that Stark would follow this departure with a work that attempts to underscore the experience of music as art and not industry.

The Magic Flute attends closely to the “fragile role of the individual artist,” while reminding us that “the un-commodifiable human voice” is something we all possess. The vocalists—the defining characteristic of the genre—have been substituted with soloists who play the vocal melodies, demanding close viewing, reading, and listening. The lyrics have also been updated through Stark’s creation of an amalgam libretto derived from the study of numerous translations that were then adapted to both fit the instrumental melodies and speak to a contemporary audience. These animated lyrics appear onscreen, immersing the viewer in the words themselves, allowing the libretto to unfold in the mind of each viewer and enabling a deeper understanding of the wit and relevance of the lyrical content. “With the libretto as the central visual focus,” Stark asserts, “the melody becomes the bouncing ball in the viewer’s head, and therefore the viewer inhabits each character.” This shift places the audience in a position other than straight spectator; they are instead a reader, a receiver, a beholder inside the art.

While many have heard of The Magic Flute, the opera remains relatively unfamiliar to most people. Stark’s film attempts to channel the narrative and underlying meaning into a beholder’s consciousness. By unpacking and restructuring the vocals, the instrumentation, the lyrics, and the form, the audience is invited to experience the work as a “pedagogical opera;” in other words, an opera that is closely read and/or taught. This artistic impulse reflects past breakthroughs in Stark’s work which have consistently reflected her attempts “to understand and manifest an erotics of pedagogy capable of voicing my poetics and challenging the art audience while also engaging youth.” By taking the original 18th-century The Magic Flute and reshuffling the conventions that are supposed to tell us the story, she produces a work of art that can show or teach us about meaning and the possibilities of art.

Concurrent with this premiere of The Magic Flute at LACMA, the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, presents a new suite of paintings by Stark in the Whitney Biennial. Recent solo exhibitions of her work include UH-OH: Frances Stark 1991–2015 which also traveled to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as well as Intimism, a survey of her video and digital works at The Art Institute of Chicago. Stark’s work has been included in exhibitions at many of the most prominent museums in the world. She participated in the 2017 and 2011 Venice Biennale, the 2017 and 2008 Whitney Biennial, and the 2013 Carnegie International, among many others. Her work first came into LACMA’s collection as an Art Here and New (AHAN) acqusition in 1997, and has been exhibited in installations such as Lost Line: Contemporary Art from the Collection (2013).