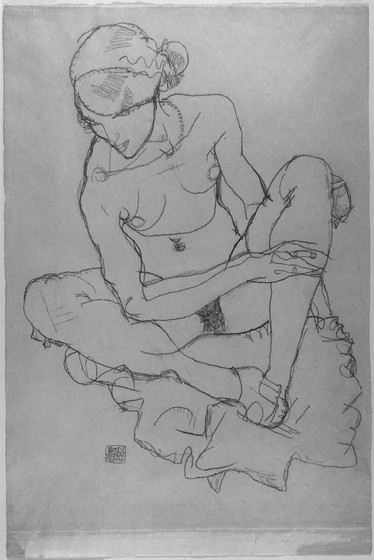

As part of my quest to collect intriguing appropriations of Art Nouveau, I found myself once again at the art house theater Cinefamily, this time to see the 1973 full-length animated film Belladonna of Sadness. Originally titled Kanashimi no Belladonna, the film, directed by Eiichi Yamamoto, was recently restored and re-released, debuting in Los Angeles and New York more than 40 years after its commercial failure in Japan. It’s a difficult film to stomach: the story revolves around a woman evocatively named Jeanne, who, after being raped by a village lord, turns to witchcraft and sorcery to avenge her assault, with catastrophic repercussions. Orgies, rape, and other scenes of sex and violence punctuate the film; even innocuous imagery is rendered vulgar, as when flowers bloom into exaggerated forms of human genitalia. Belladonna is also hypnotically beautiful, with watercolor sequences of undulating animation that morph from one frame to another. At moments the animation is painterly in a way that recalls Wassily Kandinsky’s early, Fauvist-inspired work, with an emphasis on color over form. (Kandinsky’s 1910 painting Landscape with Factory Chimney, in the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, is a good example of this period in his work.) At other times, the film’s imagery is rendered with a thin, antic line and only partially in color, lending it a sense of immediacy and rawness strongly reminiscent of the drawings and paintings of Egon Schiele and those of his mentor, Gustav Klimt.

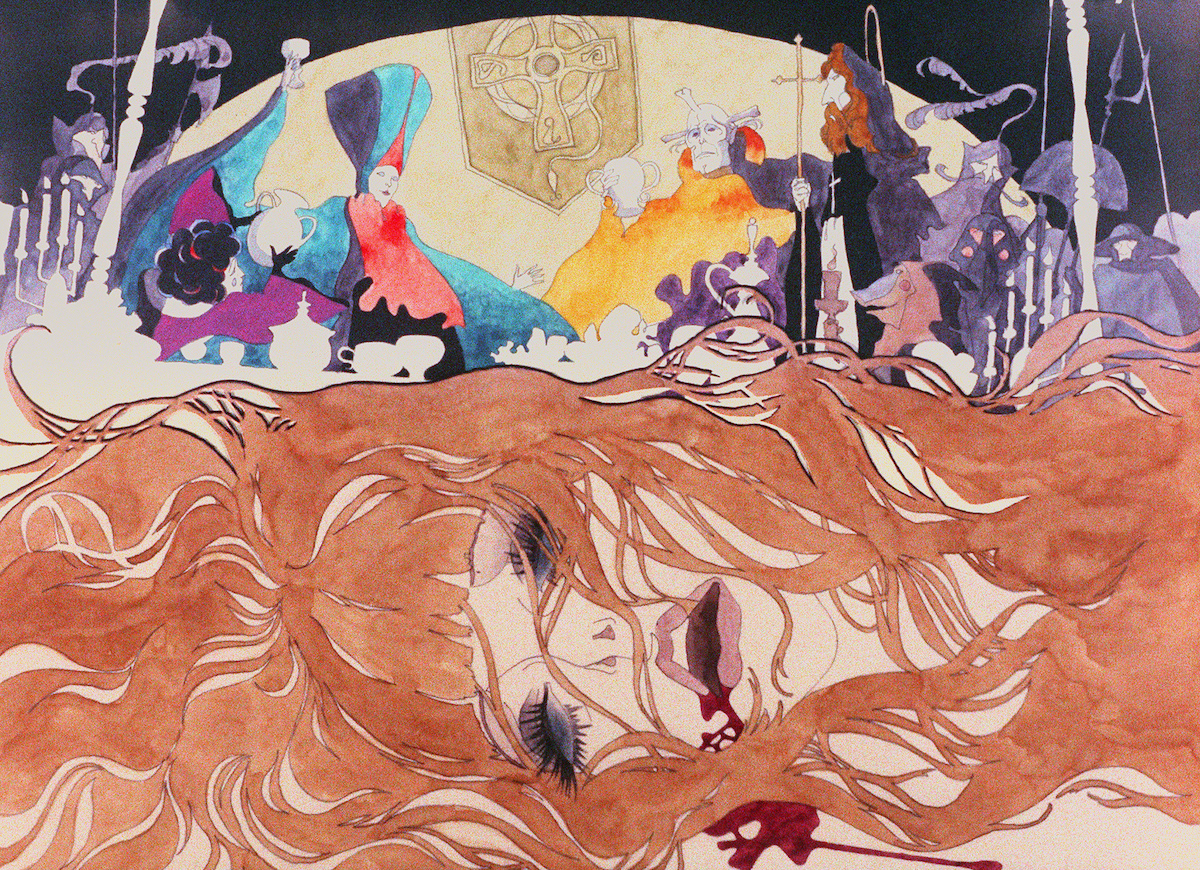

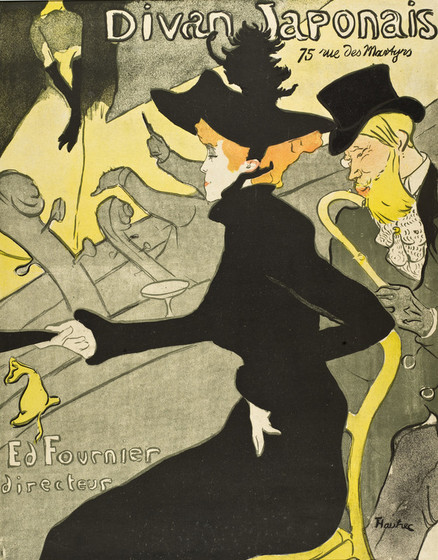

Klimt in particular shared many concerns with Art Nouveau, chief among them a desire to marry the figurative and the decorative, as his French contemporary Alphonse Mucha did so expertly. Evoking those commonalities, Belladonna is indeed rife with stylistic references to Art Nouveau, albeit filtered through the drug-fueled, free-love lens of the 1960s and 70s. Most strikingly, Belladonna sets into motion the wild tendrils of hair that metaphorically animate many Art Nouveau works on paper, from Alphonse Mucha’s prints and posters (as I highlighted in part one), to one of the most iconic Jugendstil woodblock prints, Peter Behrens’s Untitled (The Kiss), which appeared in the lushly illustrated periodical Pan in 1898. Currently on view at LACMA, the print is dominated by prodigious hair in three shades of brown, which encircles an androgynous couple kissing at the center of the composition. It’s impossible to tell whose hair is whose as it swirls around the edge of the image in all directions, symbolizing the spiritual and corporeal communion of the two figures.

Hans Christiansen’s iconic cover illustrations for Jugend, the magazine that inspired the term Jugendstil, used to describe the German cousin of French Art Nouveau, also employ wind-blown locks to lend static images a sense of exaggerated, cartoonish movement. (His designs are also frequently colored with what we might think of today as the psychedelic neons of the ’60s and the autumnal oranges, yellows, reds, and greens of the ’70s, leaving little doubt that Christiansen, alongside other fin-de-siècle illustrators, influenced the graphic tendencies of both decades.)

Belladonna transforms the dynamic coifs of Art Nouveau and Jugendstil into an occupying force. Cinematically activated, Jeanne’s hair writhes frame by frame, sometimes consuming half of the screen and threatening to overtake the image entirely, like a parasitic invading species. The film thus turns the romantic waves of Mucha’s seductresses into frightening serpents, invoking Medusa, the ur-femme fatale of Greek mythology.

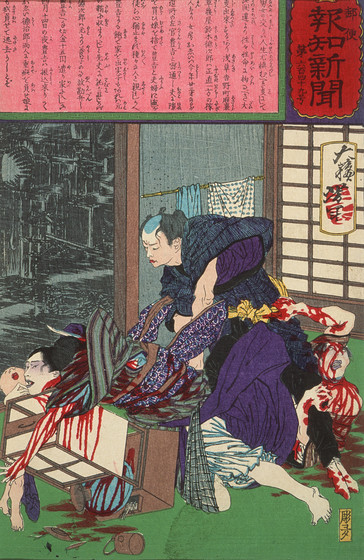

As much as Belladonna of Sadness points to Western European artistic influence, it undoubtedly also builds on the legacy of Japanese animation and what is in many ways its precedent: the tradition of Japanese woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e, and its subgenres of muzan-e and shunga. Ukiyo-e prints were first produced during the Edo Period (1603–1867) and marketed as a cheap art form for the merchant classes, despite the incredible technical skill required to make them. Such prints often pictured what was called the “floating world,” scenes of leisure and entertainment that referenced pleasure quarters, kabuki theater, and romanticized landscapes. Under the rubric of ukiyo-e, some artists, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi chief among them, drew scenes of extreme violence, called muzan-e, illustrating contemporary events and imagined warfare with exaggerated spurts of bright red blood—also a recurring motif in Belladonna (and of course in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill series, which was partly set in Japan).

Shunga, another sub genre of ukiyo-e, traded in explicit pornographic imagery, an obvious extension of the implied eroticism of relatively tame depictions of courtesans. Though “unauthorized” shunga was banned by the Japanese Shogunate in 1722, it remained a popular art form for over a century, generating several thousand publications that were mass-produced and widely circulated.

In Belladonna, shunga meets Schiele, which, oddly enough, brings us full circle. While a number of Japanese prints had arrived in Europe in the early Edo Period via Dutch traders, who had exclusive rights to trade with Japan (a period in Japanese history most recently dramatized in Martin Scorsese’s film Silence), prints flooded the Western market and had their greatest impact on European art in the 1860s and 70s, following Japan’s gradual opening to the West in the 1850s. Ukiyo-e prints and paintings had a profound impact on the trajectory of Western modernism, particularly through their flattened perspective, radical foreshortening, and graduated fields of color, which influenced the development of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Art Nouveau and Jugendstil, and many movements that succeeded them.

In bringing together the aesthetics of Japanese print culture and late 19th century European fine art and illustration, Belladonna subtly highlights those connections at the time of their broader re-emergence in 1960s and 70s design.

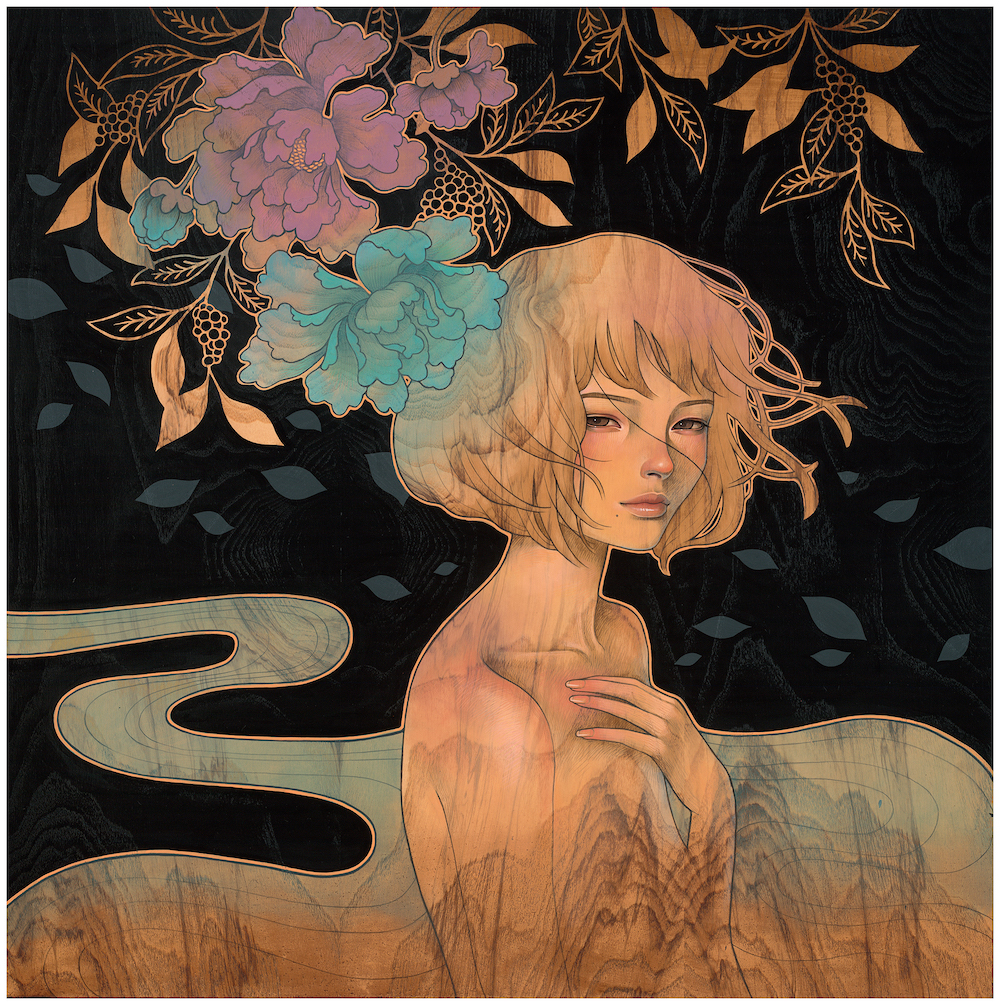

More recently, a number of Japanese and Japanese-American artists have self-consciously borrowed from Art Nouveau for works in a variety of formats, including graphic novels (Sana Takeda’s intricate illustrations for Marjorie Liu’s 2016-17 series Monstress come to mind) and countless digital illustrations freely available online (such as these Mucha-inspired portraits of characters from the films of Hayao Miyazaki). The rich fabric of references that makes up Belladonna of Sadness is also apparent in the paintings of L.A.-based artist Audrey Kawasaki, who paints portraits of young women in a style that effortlessly melds manga with hints of Art Nouveau—two art forms Kawasaki appreciates all the more, she told me, for being historically related through the tradition of ukiyo-e prints.

Kawasaki commonly paints on finely grained wood panels, and in works where the wood is allowed to show through, her paintings also nod to the many applications of Art Nouveau and Jugendstil in decorative design, including exquisite objects crafted in wood with inlaid floral patterning.

I asked Kawasaki how she developed what has become her signature style, and she named Schiele, Klimt, and Mucha (in that order of discovery) as important touchstones, largely for their strong handling of line and subtle use of color. When I asked how viewers respond to her work, especially its Art Nouveau stylistic flourishes, she described how they react to the specific character of her female figures, who have the ability to “exude sensuality, independence, and strength, yet seem so fragile and vulnerable.” It is, of course, no coincidence that Mucha’s women could be discussed in precisely the same terms, elucidating the complexity that has given them enduring appeal for more than a century.

Apostles of Nature: Jugendstil and Art Nouveau is on view in the Ahmanson Building only through Sunday, April 23, 2017. Don’t miss your chance to see it one last time!