In 1983 artist Sarah Charlesworth (1947–2013) observed, “Photography has become almost a second language, integrated as the written and spoken word into almost every aspect of social production.” At that time, she was referring to magazines, newspapers, television, and films, all of which relied on photographic images to convey information. Today, the visual landscape has shifted and image-based social media platforms rely on photographs to behave as a primary language, often in place of written and spoken forms of communication. Throughout her 40-year career, Charlesworth examined the role that photographic images play in contemporary culture—as coded forms of representation, as symbols, and as icons. Recognizing and understanding these nuances is particularly critical today as we continue to navigate our image-saturated world.

Charlesworth was closely aligned with a group of artists in the 1980s known as the Pictures Generation, which included Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, and Laurie Simmons, among others. First identified by curator Douglas Crimp in his 1977 exhibition Pictures at Artists Space in New York, these artists were concerned with how pictures mediate and govern contemporary life, specifically as we experience them through mass media. Charlesworth explored representation and symbolism, first through rephotography and by collaging found images, and later by creating stylized arrangements for the camera. Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, which opens at LACMA on August 20, includes photographs from 10 discreet series made between 1977 and 2012, arranged to accentuate her continued interest in color, form, and light.

In Charlesworth’s series Modern History, made over two years in the late 1970s, she worked with found newspapers using a systematic method of removing text, which she called “unwriting,” to produce works that explore the power of images in mass media. She focused on key news events and collected the front pages of newspapers from around the world to trace their coverage. By redacting the text but keeping the masthead, date, and photographs, a separate narrative emerged through size, placement, and angle. Installed serially, these works remind the viewer that news is shaped by its presentation and certain news stories are privileged as a result of economic, cultural, and political influences.

For her 1980 series Stills, Charlesworth clipped and rephotographed press images of people falling or jumping from tall buildings, titling each with the name of the person and the location of the incident, if known. Here the images represent a fixed moment within a continuum, excluding whatever actions may have preceded and followed the snap of the camera’s shutter. The incomplete narratives leave viewers to ponder the circumstances surrounding the images and consider possible motivations—whether a desperate act of suicide or an attempt to escape from danger. The vagueness of these images reveals the fundamental ambiguity of photographic reproduction.

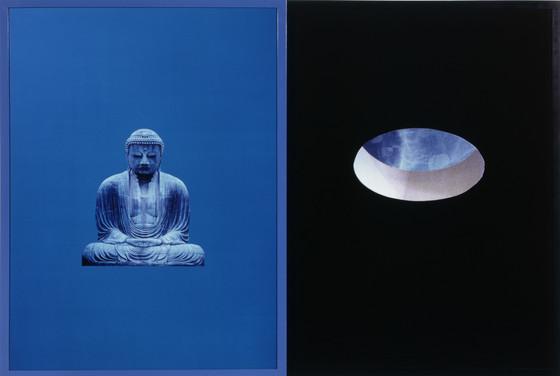

Made from 1983 to 1989 Charlesworth’s series Objects of Desire is longest running and the one for which she is best known. In it, she explores representation and the way desire is communicated in mass media and popular culture through shape and color. As a starting point, Charlesworth began with found images of fetish objects, figures, statues, vessels, and architectural fragments clipped from fashion magazines, pornography, and archaeology textbooks. In works such as Figures, she cut the clothing off the model to isolate the shape of the garment and how it embodied that person’s role in society, for instance the evening gown of the glamorous movie star contrasted with the bound figure laying on her side. Mimicking the conventions of advertising, she collaged them onto bright color backdrops like those used for product photography, and produced them in high gloss Cibachrome with matching lacquer frames. The saturated color signifies a particular type of desire: red for sexual passion, black for dominance or death, green for natural growth, yellow for material wealth, and blue for metaphysical or spiritual desire. Not only do the objects depicted elicit desire, but the conventions by which they are presented also seduce the viewer.

In Renaissance Paintings (1991) individual figures and objects from disparate, mostly 16th century paintings were isolated and rephotographed against monochrome backgrounds. Charlesworth looked specifically at the emotional thrust of the figures’ gestures and placed them in spatial relationships to evoke new meanings. The works in this series were inspired by the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, emphasizing representations of father, mother, and child. Combining conceptual precision with spiritual and emotional intensity, this series provides opportunities to reinterpret iconic paintings as open-ended narratives that evoke feelings of longing, loss, madness, and fear.

In 1992, Charlesworth transitioned from collaging and rephotographing found images to creating stylized arrangements for the camera. In her 1995 series Doubleworld, she assembled still lifes of antique cameras, stereoscopes, and telescopes—all optical instruments from the 19th century, when photography was invented and viewers were faced with navigating between the real world and its representation. The photograph Doubleworld presents two 19th-century viewing devices, each with a stereograph of two women standing side by side. The image emphasizes that representation is shaped by mechanical devices.

The works in the series 0+1 (2000) test the threshold of visual perception. White sculptural objects—a Buddha, a monkey, and a lattice screen—are set against a white background, and the scene is flooded with bright light so that only the finest edge reveals the form. Charlesworth was continuously interested in emptying out the picture plane, challenging our expectations of photographic representation. Rather than seeing sharp, distinct objects, viewers are presented with quiet and subtle images that demand focused attention. The series title alludes to the 1953 book Writing Degree Zero by influential French literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes, who extolls writing that is devoid of literary tropes and free of style and conventions. By keeping the visual information in her images to a bare minimum, Charlesworth aims to achieve what she calls “image degree zero,” formulating her own question: Where do images begin and end?

Available Light (2012) is Charlesworth’s final series and it incorporates many of her techniques utilized over the course of her career: photographing isolated objects in front of monochromatic backgrounds, arranging objects and images in the studio, and testing the possibilities of photography’s central component—light. Relying solely on the available daylight from her studio window, Charlesworth photographed glass spheres, prisms, metal objects, and other reflective materials to produce luminous images with a subtle palette of whites, silvers, and blues. By placing a sheet of vellum over the window, Charlesworth evenly diffused the light and controlled its direction using a series of reflectors. She adhered segments of blue paper to the window to produce bands of blue light. Charlesworth emphasizes that all images are constructed and even the “spontaneous” photograph is composed by the artist’s hand, framing choices, and available light. This message is increasingly important for a contemporary audience who is awash in a sea of images that test, expand, and challenge visual literacy.

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld opens in the Art of the Americas Building on August 20. Member Previews begin August 17. Join now to experience this exhibition before it opens to the public!