As we in the United States have witnessed so recently, the power and fury of rainstorms can be devastating. The ancient Maya contended with these natural forces, too. They envisioned the awesome strength of wind, rain, and other natural phenomena as animate, supernatural beings. Through worship, prayer, and offerings, such beings were communicated with, called to action, and appeased. These animate beings, embodiments of the natural world, were represented in art, painted in ceramic vessels, drawn on screenfold books, and sculpted in stone. This post describes one such being, of lightning, rain, and wind, that was sculpted 2,000 years ago. That it feels relevant today helps forge a meaningful connection between ourselves and people who lived far away and long ago. They, too, experienced the destructive capability of the natural world and sought, in their own way, to protect themselves against it.

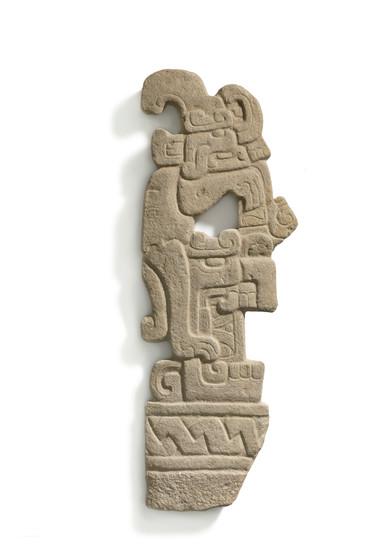

Sculpture with Rain Deity was likely carved during the Terminal Preclassic period (c. 100 BCE–CE 150) at a site called Kaminaljuyu (ka-mee-nal-hu-YU). The majority of Kaminaljuyu is now destroyed, as the site has been buried beneath modern-day Guatemala City. During its heyday, Kaminaljuyu dominated the Valley of Guatemala, a key trade and migration corridor that cut through the Sierra Madre mountain chain, connecting the Pacific Coast to the lowland areas and riverine systems that lie northward.

.jpg)

I have spent more than a decade documenting sculptures from Kaminaljuyu. The vast majority of these were broken in antiquity, so my study has predominantly focused on fragmentary bits and pieces. To find a complete monument from Kaminaljuyu, and one that is so well preserved, is remarkable. Dr. Megan O’Neil, LACMA’s associate curator in the Art of the Ancient Americas, rediscovered this sculpture in the museum’s holdings in early 2016. Recognizing its style as diagnostic of Kaminaljuyu, Dr. O’Neil invited me to visit. I arrived a few months later and, confirming the monument was, indeed, from Kaminaljuyu, I spent a few delightful hours photographing and drawing it.

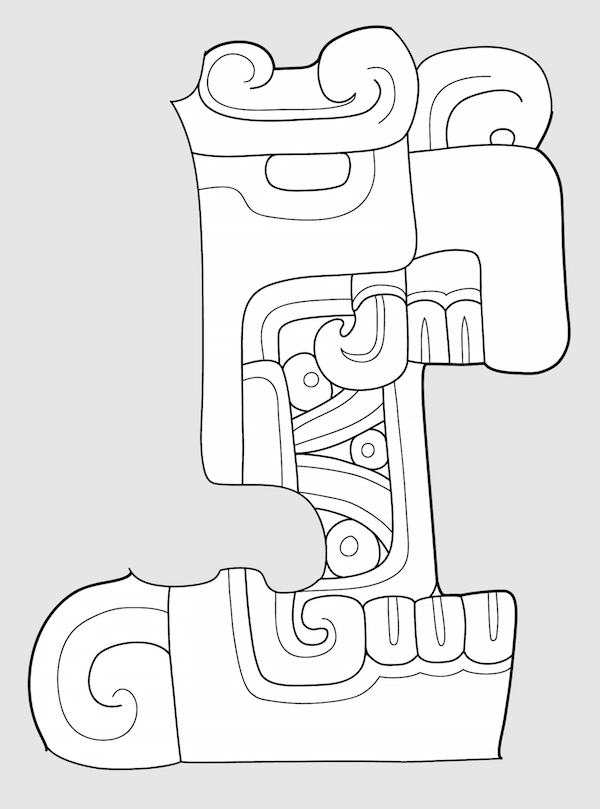

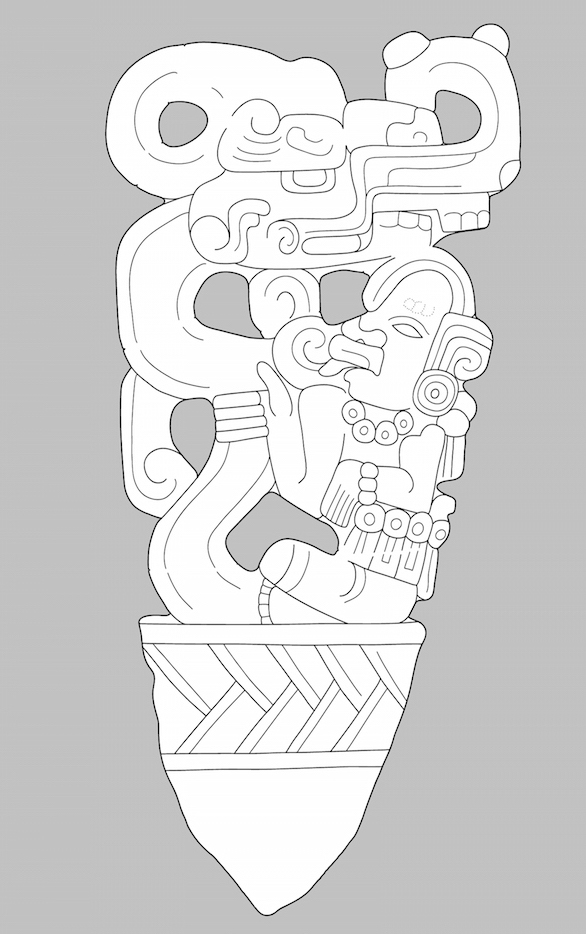

The photographs and sketch from that visit were combined to produce the illustration you see here. Maya scholars often rely on drawings of sculptures rather than photographs. Photographs, due to the play of light and shadow across a carved surface, can often be unclear or misleading. Black-and-white drawings provide a clearer, more legible rendition of a sculpture’s iconography.

Artists at Kaminaljuyu produced some of the finest sculptures of the early Maya world. The type of sculpture pictured here is known as a “silhouette” sculpture, a format almost wholly restricted to Kaminaljuyu. Silhouette sculptures are thin stone cutouts, plain on one side and carved on the other with elaborate bas-relief iconography. The sculpture’s uncarved base would have been pushed into the ground, holding the monument upright. Silhouette sculptures are some of the great masterworks of early Maya art, particularly given that these volcanic stones were immensely hard, stone cutouts are extremely brittle, and ancient Maya artists did not have metal or mechanized tools to assist them in their work.

There are two basic components of this sculpture. The first is the full-bodied creature that leans across the top of the composition, a form without parallel in the natural world. It has a strange face with an up-curled snout and a forehead that curves backward in a fin-shape. It has an animal body, paws instead of hands and feet, and a long feline tail that curls at the end. This appears to be a composite creature, combining supernatural features associated with rain, lightning, and wind.

The jaguar body, back-curving crest, part of the face, and the shell earflare are all associated with imagery of the early Maya rain god. As Dr. Karl Taube, a specialist in Maya iconography, has shown, Maya rain gods appear to have developed out of an Olmec tradition of jaguarian rain deities. In fact, these deep connections are so long-lived that rituals involving jaguars and rainmaking are encountered today among several contemporary indigenous groups. Such close connections explain the animal paws and curling jaguar tail encountered in the Kaminaljuyu sculpture.

During the Terminal Preclassic period, Maya artists began to show their rain gods with a back-curving fish fin atop their heads. Sometimes these are reduced to a simple bump, while in other cases they are enlarged, curling back as though the fin has been transformed into a swirling raincloud. The figure’s face—including his large, round eye, upper mouth, and curling fish whisker—further identifies him with rain god imagery, while his cut-shell earflare is frequently seen on early Maya rain deities, becoming a diagnostic feature of the Classic period rain god, Chahk.

One unusual feature of the Kaminaljuyu figure is the light pattern etched into his back and the markings at his hip joints, which together seem to indicate that he is wearing something around his torso. It is possible that this alludes to a turtle shell or another hard carapace of some kind. In ancient Mesoamerica, the earth was envisioned as a great turtle floating on a primordial sea. It is thus possible this subtle design element refers to world centers and cosmic models, though these connections are tentative at best.

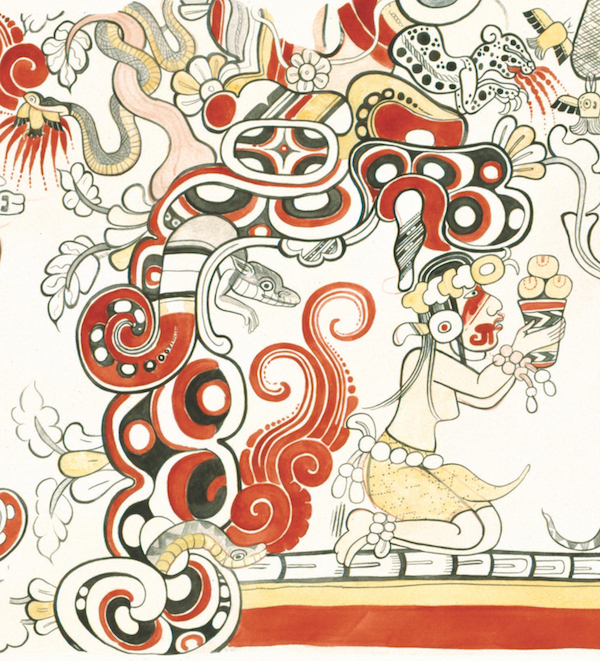

The most obvious feature that sets the Kaminaljuyu image apart from other images of the rain god is his long, upward-tilting snout. In general, the early Maya rain god is depicted with a short snout. Here, however, his upper lip is elongated and curls dramatically upward, revealing a row of skeletal teeth. Dr. David Stuart, a specialist in Maya iconography, has recently identified this particular set of serpent features—bared teeth and a long, upturned snout—as diagnostic characteristics of lightning serpents. These creatures are also frequently shown with the same eyebrow as that encountered in the Kaminaljuyu image. Lightning serpents are usually seen at the ends of skybands in early Maya art, where they shoot downward amid scrollwork and moisture signs. On the façade of an Early Classic building at Copan, Honduras, one such lightning serpent is shown mid-strike. Chahk, the Classic period Maya storm god, rides on its back wielding a flashing lightning axe.

On the Kaminaljuyu sculpture, liquid or vapor curls out of the deity’s mouth in a scroll. The end of the scroll is decorated with two small teeth. This rather unusual addition may allude to the Kaminaljuyu wind deity, who is depicted with a similar bucktooth or buckteeth. Another sculpture from Kaminaljuyu shows a similar set of elements as our silhouette sculpture although here they are combined somewhat differently. In this image, a seated, bucktoothed wind deity holds a writhing lightning serpent in his hand. This lightning serpent has the same back-curving fish fin that we see atop the head of the rain deity on the LACMA sculpture. Both of these Kaminaljuyu sculptures, then, fuse features of the rain god with that of lightning serpents.

The crouching creature on our original silhouette sculpture, then, is a storm god, with a jaguar body and a fish-fin atop his head, exhaling a scroll of gusting wind out of his flashing lightning snout. He is, in other words, the embodiment of a tremendous thunderstorm.

Our storm god hunches over a large, open-mouthed face. Facing to the right, the eye of this creature is visible beneath a scrolling eyebrow. His nose is perched atop an upper lip that bends sharply downward, revealing a row of large teeth and a fang below exposed gums. Such skeletal teeth are usually associated with the dead and Underworld themes. Within this mouth is a hieroglyphic sign that reads “ak’ab,” meaning darkness or night. This sign tells us that we are gazing into a place of darkness when we look into this creature’s gaping mouth.

At Kaminaljuyu, we encounter similar mouths and teeth in representations of jaguars and snakes. Both of these creatures, coincidentally, are associated with darkness and caves. Throughout the Maya world and throughout Mesoamerica, open animal jaws were equated with entrances to the earth, particularly mountain caves. In the Terminal Preclassic murals of San Bartolo, for example, a cave is animated with an eye and a mouth with a stalactite fang (note the cave’s exterior is marked with “ak’ab” signs).

We can thus confidently identify the lower face on the Kaminaljuyu monument as a representation of a mountain cave. That a storming rain god would be depicted crouching atop a mountain cave is not surprising. In ancient Maya belief, mountains and caves were not only envisioned as the origin points for rain and clouds, but as the homes of rain gods.

To the ancient Maya, the world was alive. Geographic features and natural phenomena were envisioned as animated, living beings. As such, storm gods and mountain caves took on physical, embodied forms. The silhouette sculpture from Kaminaljuyu presents us with a perfect example of this fully animated world. In effect, a curving jaguarian storm god hunched over a cavernous mouth represents a violent thunderstorm issuing from a mountain cave.

This important sculpture will travel to China in 2018–19 as part of LACMA's exhibition Forces of Nature: Ancient Maya Arts from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, curated by Megan E. O'Neil.

Lucia Henderson received her PhD in art history from the University of Texas at Austin in 2013. She holds an MA in art history from UC San Diego, a BA in archaeology from Harvard University, and is a trained archaeological illustrator. Lucia is a specialist in the iconography of the early Maya and the Southern Region of Mesoamerica (c. 500 BCE–150 CE). Her broader research interests stretch across a diverse range of topics, from sculptural iconography to cave art, hydraulic systems, landscape imagery, and the ideology and symbolism of incipient rulership. Her published work covers two millennia, from the 6th century BCE through the 16th century CE and discusses cultures as diverse as the Maya, the Aztecs, and the Hopi of the American Southwest.

FOR FURTHER READING

Brady, James E. and Keith M. Prufer (editors). 2005. In the Maw of the Earth Monster: Mesoamerican Ritual Cave Use. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Guernsey, Julia. 2010. A consideration of the quatrefoil motif in Preclassic Mesoamerica. Res 57/58:75-96.

Henderson, Lucia R. 2013. “Bodies Politic, Bodies in Stone: Imagery of the Human and the Divine in the Sculpture of Late Preclassic Kaminaljuyú, Guatemala.” Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Art and Art History, University of Texas at Austin.

n.d. “Frente al paisaje: la iconografía del mundo natural en el arte Preclásico.” To be published in XXXI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2017. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala City.

Orr, Heather S. 2001. Procession Rituals and Shrine Sites: The Politics of Sacred Space In the Late Formative Valley of Oaxaca. In Landscape and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica, edited by Rex Koontz, Kathryn Reese-Taylor and Annabeth Headrick, pp. 55-79. Westview Press, Boulder.

Saturno, William A., Karl A. Taube, David Stuart and Heather Hurst. 2005. The Murals of San Bartolo, El Petén, Guatemala. Part 1, The North Wall. Ancient America, No. 7. Center for Ancient American Studies, Barnardsville.

Stuart, David. 1997. The Hills are Alive: Sacred Mountain in the Maya Cosmos. Symbols Spring 1997:13-17.

Taube, Karl A. 1995. The Rainmakers: The Olmec and Their Contribution to Mesoamerican Belief and Ritual. In The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership, pp. 83-103. Harry N. Abrams, New York.