Ever since Jacob Samuel set up his Santa Monica workshop in 1988, artists have turned to this master printer for his unparalleled insights into how centuries-old techniques can be applied to make contemporary prints. The archive of Edition Jacob Samuel has been jointly acquired by LACMA and the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

For Artists on Art, LACMA’s online video series featuring contemporary artists speaking on objects of their choice from our permanent collection, Samuel selected seven early-16th-century prints by Albrecht Dürer. Today, he speaks more about his connection to these works.

We’re looking at a whole array of prints by Dürer—where to begin?

Well, they are all engravings. Dürer did make a few etchings in his lifetime, but he is really known as the master engraver. These prints are over 500 years old. As a master draftsman, he is completely unequaled. Through line, Dürer was able to create all these different textures. When you look close you see incredible clarity in the spacing between the lines, and how [the plates were] wiped so cleanly that there is absolutely no ink in the white areas.

Each of these images offers extraordinary detail, both in terms of texture and the density of the narrative.

One of Dürer’s greatest prints is Melencolia I, which is such a loaded image—an allegory. Right away you notice the tools. And [you notice] the principal figure, be it man or woman, angel or person. Why would an angel be holding a compass? This has to do with the world and achievement and science. There is a funereal bell here; there is an hourglass. There is this incredible juxtaposition in terms of the symbols in this print, between what people do, which is work with tools—there is a saw, there is a plane, a compass—and the sense of contemplation. It’s all leading into this ultimate feeling, “melencolia,” which asks, what can a person do? We have all of these tools at our disposal and are able to begin to create the modern world. A perfect sphere, for instance. But also there is mortality. Dürer is juxtaposing what a human can do, in view of our ultimate mortality, and the contemplative stare of this being with wings. It’s a really incredibly loaded image, and that’s why it’s considered one of his great masterpieces.

Can you tell us a little more about the tools and materials Dürer used?

He used a burin [which is still used by engravers]. Engraving is the most difficult printmaking technique. A burin is a metal shaft cut in the shape of a diamond tip—a diamond like on a playing card—with a little wooden ball on the end that you hold in the palm of your hand. The shaft comes through your fingers and you are going through the copper in this kind of excavating motion. The artist would have the plate on a little pillow, and would move the pillow around. So the line carved is always kind of straight, and the movement of the plate is what’s creating these curves. So, factor that degree of difficulty in—number one. Number two, Dürer is using different sized tips of burins. But think about this: it’s 1500, and you have to manufacture these very precise tools. He is able to get very fine lines, which will all hold ink. He is able to carve these unbelievable patterns and subtleties into the copper. That says something about the sophistication of the technology at that point.

You’re referring to the copper plates into which Dürer engraved before printing onto paper.

Yes, and let’s talk about the copper just for a second, because they [Renaissance artisans] had to manufacture copper. There were copper mines, and there was copper ore, and they had to smelt and purify it. And then they had to pound the copper out into plates and cut it. This was a highly laborious process. The copper plates were very expensive to manufacture, they were prized and cherished. There really wasn’t room for any margin of error. Because if you do not have a perfect plate, you are not going to have a perfect print.

Can you tell us about the ink used?

The way they made inks—the way inks are still made—resulted in a variety of blacks. So there’s black made out of charred bones. That’s called bone black. And then there is a vine black, where you would take leaves and burn them and use that for your pigment. In some prints you’ll notice there is a grey tonality to the ink. What artists would do at that time, Dürer included, is include ash from squash, from pumpkins, in the ink, and this would create a silver luster. It was all a matter of the density you wanted for the ink, the tonality you wanted of the ink, the ease you wanted for wiping—if you wanted some tone left on the plate or if you wanted it to be wiped clean.

And it’s also worth mentioning the wipe—that aspect of the hand required of master printers.

So, the plate would be wiped with a soft cloth, to impress the ink into all the engraved lines, and then that plate would be put on a hot plate so the ink remaining on the surface [not actually in the lines] could be wiped off very easily. But what it really comes down to is the hand-touch of wiping the plate. Sometimes there is a tone over the whole plate that gives an atmosphere. In Dürer, it’s beautiful to see that kind of interpretation.

These are striking moments of genius, so to speak, from a working craftsperson.

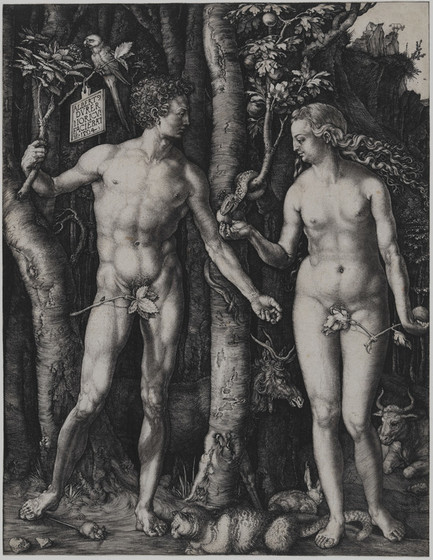

Dürer was obviously very proud of [Adam and Eve, 1504], because unlike the other prints where he just has a little monogram of his initials, he signed it “Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg did this in the year which is 1504.” From looking at earlier [working] proofs of this print you can see that he left the figures to the end, and worked on the background beforehand. The background is so rich and dense, and yet clarity is still maintained even in the darkest areas. There are really subtle grays going on inside the blacks. He is able to hold detail in all of these areas and at the same time create such a coherent overall composition.

Myriad details evoke the narrative of creative genesis?

One thing about all of these images that’s important to understand is that we are dealing with somebody of acute intelligence who is loading up the imagery nonstop. The symbolism in these images is layered. It’s a mind at work. It’s not just facility. Dürer is really communicating here, which is what great art does. At this period in time, around 1500, to see him able to synthesize this incredible mastery with an understanding of history, an understanding of religious iconography and the symbolism of his day, and to bring it all together in lyrical imagery, is absolutely astounding. That’s why, after 500 years, we are still looking at these prints and marveling.

The conversation was edited and condensed for clarity.