“Sarah practiced a pedagogy that encouraged research, freethinking, and dialectics, and was adored by her students.” —Betsy Sussler, editor-in-chief of BOMB magazine

In a final salute to Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, which will be closing February 4, we reached out to two of her former students for their thoughts on her legacy as an artist and her equally inspirational career as a teacher to numerous generations.

Kevin Cooley is a Los Angeles-based multidisciplinary artist whose work focuses on the elemental forces of nature in order to question systems of knowledge. Using photography, video, and installation he investigates our evolving relationships to nature, to technology, and ultimately to one another. His work will be on view locally in February.

Matthew C. Lange is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. Since receiving his MFA in Photography, Video and Related Media from the School of Visual Arts in 2011, Lange has staged performances and exhibited work at MoMA PS1, LIC (NY), Printed Matter (NY), CCNY Baxter St. (NY), NurtureArt (NY), and Signal Projects (NY). In addition to serving as a lecturer at School of Visual Arts and CUNY, New York City College of Technology, Lange is the studio manager for the Sarah Charlesworth Estate.

How did you come to know Sarah Charlesworth's work—did you know of her work before she was your teacher?

Cooley: I first learned of Sarah's work from a [1985] Whitney Biennial catalogue I found in my college library. While I didn't realize she taught at SVA when I applied to graduate school, as I mostly applied to West Coast schools, I was very excited by the possibility of having her as a critique instructor.

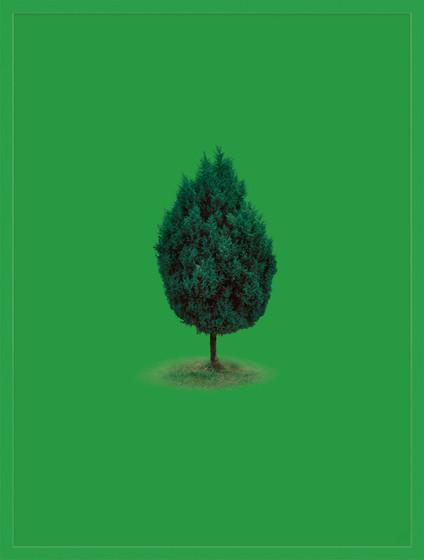

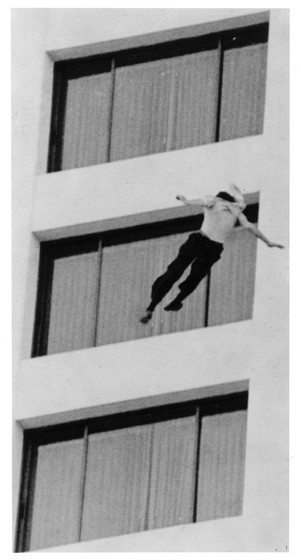

Lange: The specter of the Pictures Generation loomed large in my undergrad program. There are particular works by Sarah that I remember seeing in books and lectures. As I was applying for grad school, I went to an exhibition at the Met that included one of Liz Deschenes's green screen pieces and one of Sarah's Stills. I was completely taken by both of these works. I didn't immediately realize that both artists were instructors at SVA, but when I did, they were certainly a major factor in my decision to enter that program.

What was her teaching and critique style like?

Cooley: Sarah was often brutally honest when evaluating student work, but she did so in a way that remained inspirational. She had a way of seeing things in the work that nobody else in the room could see. Cutting through technical or other inadequacies, she always, often immediately, understood what was happening fundamentally in the work, and had a way of challenging students to channel that energy into making their work better.

Lange: I was very lucky to see Sarah's teaching style from a few different vantage points: as her student, as her assistant while I was her student, as her assistant while she prepared for grad and undergrad courses after I had finished at SVA, and as her TA at Princeton. I had the opportunity to see how seriously she took her role as an instructor, and how deeply she cared about the growth of younger artists in her course. Sarah was simultaneously very rigorous and very nurturing. She could come across as cold or unforgiving, but she also invested in all of her students' work, often in ways that they never realized.

How did your understanding of her work change after interacting with her directly as a teacher?

Cooley: I studied with her in 1999 and worked for her after grad school. I really got to know her and her work from my brief time working in her studio. Sarah was a very generous person, and she often insisted on driving me home after work, which provided me the opportunity to ask her questions. She was working on her 0+1 series at the time and had a lot of questions about them. I clearly remember being stuck in traffic on the Williamsburg Bridge and she was talking about her mother, who had recently passed, and at some point in the conversation I suddenly realized I finally understood the power, the elegance, and the perfectly executed simplicity of her work.

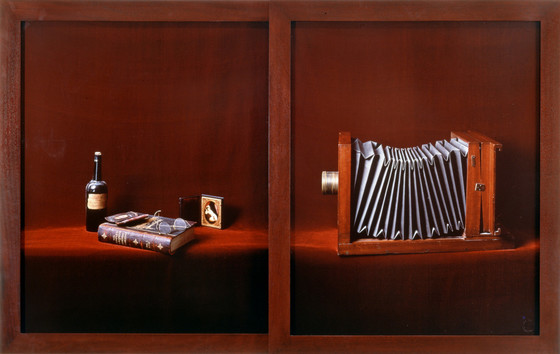

Lange: My understanding of Sarah's work changed profoundly as a result of seeing her work as an instructor. Perhaps the most important realization was that her work is contingent on an exactitude of thought that is nearly impossible for most people to fathom, especially in an age of digital distractions. This is reflected in the deceptively minimal forms that she employs, the clarity of her concepts, and the specificity of the objects that she creates. When I came into Sarah's critique I read her early works as these bold, declarative, conceptual statements. They seemed to have a cool precision and an audacity. But there is also sensitivity, thoughtfulness, and a contemplative depth to all of Sarah's work. And the early work would fall flat if it weren't for these things.

Can you point to any elements in your own practice—actual work or your approach—that can be traced directly or indirectly to Sarah? Let's call this the Sarah Effect; she may have simply inspired you to look in another direction...

Cooley: The Sarah Effect, I like that. Absolutely. I came to SVA as an overconfident street photographer with no idea of conceptual art. Through Sarah's insight into how to look at the world in another way and how she thought of photography as a problem all its own, rather than as a visual solution to something else, she pointed me to question everything I knew about looking, about seeing and understanding what was around me. Between her and Andrew Ginzel, who encouraged me to think beyond photography, I had a whole new set of tools, and a new understanding of what my art could be.

Lange: I've attempted to put into practice some of Sarah’s qualities—precision, rigor, contemplation—though I'm certain that I fail at all of these things, at least in the way she exercised them. My own work, until early last year, was focused on a project that began as my MFA thesis. At the center of this was a series of confusing, eclectic, sometimes incoherent performative lectures based on a nonsensical premise. Early on Sarah told me she couldn't quite understand why she liked what I was doing. This was her way of telling me to keep pursuing that direction without overthinking it. Now, I think the project was heavily influenced by a set of concerns around language, meaning, and imagery that Sarah played a major role in defining.

Any residual effect on your own teaching style now?

Cooley: For the past couple of years, I've essentially taught that same critique class I had with her in the MFA photography department at SVA. While I'm not sure I could ever harness the level of insight that she possessed, she continues to be an influence on me as an artist, as an educator, and as a human being.

Lange: I'm lucky to teach in a couple of very different contexts, which bring out different elements of Sarah's influence. When I teach in the Honors Program at SVA, I always try to emphasize the importance of critical engagement for any kind of art practice. Sarah’s approach certainly affirmed that artists should be conscious of these issues. I also teach digital photography to Communication Design students at CUNY, which has students at all different skill levels and with a whole range of concerns such as economic instability, Islamophobia, or immigration status. I hope that I can impart some methods for using photographs to convey meaning, and I'm grateful that Sarah showed me a few things about how to help a young artist realize their ideas.

If you're interested in learning more about Sarah Charlesworth's practice, join us for an artist talk with Matt Lipps tomorrow, January 30, at 7 pm.